- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:Heinrich Biber

-

作曲家:Marco Uccellini

-

作曲家:Andrea Falconieri

-

作品集:Dance Suite

-

作曲家:Jean-Henri D'Anglebert

-

作曲家:Giovanni Antonio Pandolfi Mealli

-

作曲家:Jacob Van Eyck

-

作曲家:John Bull

-

作曲家:Bartolomeo de Selma Y Salaverde

-

作曲家:Giovanni Battista Fontana

-

作曲家:John Bull

-

作曲家:Marco Uccellini

-

作曲家:Arcangelo Corellli

-

作品集:Violin Sonata in C Major, Op. 5 No. 3

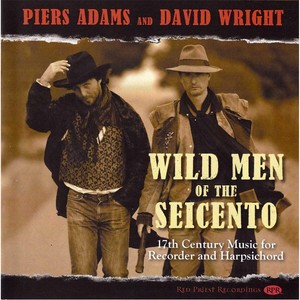

简介

The Seventeenth Century – or Seicento in Italy – was arguably the wildest, most experimental period in the history of Western art music. This was a time when composers broke away entirely from the constrictions of the Stile Antiquo (old style) of the previous centuries – in which music generally had a religious or social function (sacred choral music, courtly dances) – towards a new, abstract art-form free of boundaries or context. This new style was referred to as the Stile Moderno, and later, the Stylus Phantasticus, and its exponents could be compared to Stravinsky, whose Rite of Spring created such a furore some 300 years later – or even to the punk rockers of the 1970s! The inspiration for this new style came largely from the birth of opera, under the quills of Peri and Monteverdi, who experimented freely with harmony, taking pleasure in the use of dissonance to startling effect. At the same time came the beginnings of a highly dramatic approach to performance, with performers expected to study the science of rhetoric, and to apply the techniques to their playing and singing to heighten the emotional impact of the delivery, through vivid use of light and shade, and a highly flexible approach to rhythm. The first sonatas and canzonas were simply instrumental breaks within the opera, but soon composers began developing these pieces as entities in their own right, and the instrumental sonata proper was born. These early works, by composers such as Fontana and Uccellini (Italy) Selma (Spain/Austria) and Bull (England), were characterised by rapid and angular changes of mood and tempo, with bursts of rhapsodic intensity, playful dance sections and soulful melodies. The idea of regularity - a fixed beat, even phrases, predictable harmonies - were anathema to these musical pioneers, and indeed this rebellious spirit of adventure was to continue well into the ‘high baroque’ era. As the Seicento progressed the Stile Moderno took wings and developed in many different directions, both stylistically and geographically. The music of the Pandolfi Mealli and Biber take things to their logical conclusion in terms of the bizarre – the latter taking on an almost Pythonesque surreality. Other composers preferred to work within more definable styles, such as dance and variation formats (respectively Falconiero and Van Eyck), whereas the freedom of the style found a looser, more sensuous voice amongst French keyboardists such as D’Anglebert. But by the end of the century the wildest experimentation had given way to more formal structures, the rapid-fire musical ideas expanding and crystallising into extended ‘movements’, and this change was formally marked on Jan 1st 1700 with the publication of Corelli’s Opus 5 – a set of twelve violin sonatas which were to become the benchmark for instrumental sonatas thereafter. Despite the increased formality of structure, the rhetorical, emotional aspect of music-making remained at the fore, and role of the performer was as great as ever, as this contemporary description of Corelli illustrates (Ragunet, 1702): “I never met with any man that suffered his passions to hurry him away so much whilst he was playing on the violin as the famous Arcangelo Corelli, whose eyes will sometimes turn as red as fire; his countenance will be distorted, his eyeballs roll as in agony, and he gives in so much to what he is doing that he doth not look like the same man.” Finally, a word on instrumentation: most of the music in this concert was originally composed for the violin, but the recorder remains a valid choice for all except possibly the highly idiomatic violin music of Biber. Contemporary accounts describe musicians adapting these works successfully for the recorder, and certainly the virtuosity of Van Eyck (the only true recorder composer in this programme) is not in doubt. Such was the popularity of the instrument, especially in amateur circles, that Corelli’s entire Op 5 was published in an arrangement for the recorder within a year of its original appearance. ‘A rare treat to have an action-packed recital recording……..[with] thrills…….reflective, lyrical works …..all manner of technical devilry with superhuman virtuosity, a laughing recklessness and style you can’t buy……exquisitely rendered by Adams and Wright…’ Gramophone ‘…a showcase for Adams’ lightning-quick, virtuosic style…….. [and] carefree suavity of Wright’s harpsichord solos’ Early Music Today Piers Adams’s bravura playing is what immediately strikes the ear, with his use of a range of modern (and loud) recorders, but it would be a mistake to ignore David Wright’s wonderfully varied accompaniment which helps to create every change of mood and achieves a remarkable range of dynamics. Early Music Review The improvisatory meanderings which commence the opening item, Heinrich Biber’s Sonata No.3, are instantly hypnotic: Adams and Wright wander from ethereal reflectiveness to rhythmically ebullient dance-like interjections, and intersperse exuberant explosions of incessantly repeating melodic fragments. The virtuosity is simply astonishing – almost implausible. In the recorder’s crazily precipitous flights of fancy, every note is articulated cleanly and purely, no matter how many such notes there seem to be in a single second. The triple and quadruple tonguing, and the multiple tones, produce the incredulity that one feels after witnessing a conjuror’s sleight-of-hand: have our ears deceived us? The riches of this disc are multifarious: musical, technical, interpretative and expressive. MusicWeb International