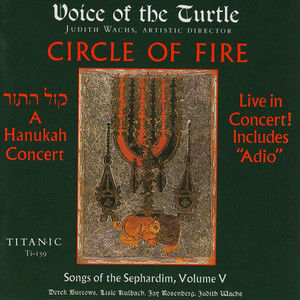

Circle of Fire: A Hanukah Concert

- 流派:World Music 世界音乐

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:1987-12-01

- 类型:演唱会

- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

The Baal Shem Tov used to go to a certain place in the woods and light a fire and pray when he was faced with an especially difficult task, and it was done. His successor followed his example and went to the same place, but said: "The fire we can no longer light, but we can still say the prayer." And what he asked was done too. Another generation passed, and Rabbi Moshe Leib of Sassov went to the woods and said: "The fire we can no longer light, the prayer we no longer know; all we know is the place in the woods, and that will have to be enough." And it was enough. In the fourth generation, Rabbi Israel of Rishin stayed at home and said: "The fire we can no longer light, the prayer we no longer know, nor do we know the place. All we can do is tell the story." And that, too, proved sufficient. --A Big Jewish Book Jerome Rothenberg, ed. with Harris Lenowitz and Charles Doria. Anchor Books, Anchor Press/Doubleday, Garden City, N, 1978. Voice of the Turtle, Judith Wachs, Artistic Director "The flowers appear on the earth, the time of singing is come, and the voice of the turtle (dove) is heard throughout the land." - Song of Songs Derek Burrows: Spanish medieval bagpipes, flutes, mandolin, saz, guitar, percussion, and voice Lisle Kulbach: rebec, medieval fiddle, violin, shawn, percussion, and voice Jay Rosenberg: 'ud, tenor chalumeau, cornetti, guitar, percussion, and voice Judith Wachs: soprano chalumeau, recorder, baglama, percussion, and voice CIRCLE OF FIRE, broadcast by WGBH-FM Radio, Boston, was heard on 89 stations of the American Public Radio Network. It was the ninth annual concert for Hanukah given by Voice of the Turtle. The music is the legacy of the Sephardim, the Jews who lived for more than 1500 years in Spain and Portugal, before their expulsion at the end of the 15th century. The Spanish Inquisition forced them into exile, but they continued to sing and speak the language of their ancestral homeland as well as preserve their Hebrew heritage. The selections on this recording come from the huge repertoire of wonderful music that the Sephardim preserved by oral tradition for more than 500 years.The songs were collected from Sephardim who lived in the Ottoman Empire and in North Africa and represent a wide variety of cultural and musical traditions. The Sephardim use any celebration or social gathering as an opportunity for singing, mixing the songs for the occasion with the favorites of the singing guests. This program was conceived in that spirit. HANUKAH Hanukah is the festival which commemorates the successful Jewish revolt led by the Maccabees in 165 B.C.E. Under the rule of the Greeks, Jews were required to adhere to Hellenic life and custom and had thus lost the right to observe their religion, On the 25th day of the month of Kislev, the Maccabees -Mattathias (the father) and Judah and his brothers- defeated the ruler Antiochus and reclaimed the Temple in Jerusalem which had been defiled and desecrated. After having cleansed and purified the Temple, the Maccabees rededicated it (Hanukah mean "dedication") and rekindled the lights of the menorah, the seven-branched lampstand. According to legend, the only remaining purified oil was sufficient to last for a day, but miraculously burned for eight days. By lighting the lights of the menorah for eight days, beginning on the 25th day of the month of Kislev, Jewish people remember the miracle of the oil and the triumph of the small band of people who fought for, and won, the freedom to act according to their beliefs. RITES AND SYMBOLS In any people’s tradition, there have been few more compelling symbols than those of FIRE and LIGHT, the central symbols of Hanukah. Although the second century texts, 1 and 2 Maccabees, do not mention the kindling of lights , by the fourth century the historian Josephus refers to the holiday as the “Festival of Lights” and alludes to the freedom which glows and lights up Jewish life. The rites bear striking resemblance to those of a much older nature festival of fire and lights observed by certain Jewish groups in winter as the days began to lengthen. And it is conjectured that under Kig Herod the Jews were not likely to have been allowed to celebrate the successful revolt of the Maccabees and, therefore, preserved only the kindling of lights, which could be explained as an old folk custom. This kind of ruse can be discovered later among the Sephardic Jews whose holiday rituals, proscribed by the Church, were distorted just enough to fool the authorities. By the sixth and seventh centuries 9C.E.) the story of the miracle of the flask of oil is firmly ensconced as the central legend of the holiday. The lightling of the Hanukah lamp is then common to all Jewish communities. The menorah, the seven-branched lampstand, has been the most persistent emblem of the Jewish people, as well as the symbol of the holiday of Hanukah. Like most symbols whose emotional impact has persisted through ages and cultures, the menorah springs from ancient lineage – tree cults (whence the design), astrology and astronomy, and legends which allude to the Tree of Life. Today the Hanukah lamp is called a Hanukiah. It has eight kindling places, and often one or two extra, the number varying among different Jewish communities. HEROINES AND HEROES The story of the triumph of the courageous Maccabees, who set historic precedent by waging war in defense of their beliefs, is recounted from generation to generation. But it is rare that one hears that the story of the valor and intelligence of the Biblical heroine Judith inspired the Maccabees. And the legend of how Judith made Holofernes vulnerable to attack by giving him a salty cheese to encourage his wine consumption has inspired delights of the palate which include cheese in Hanukah dishes. The story of Hanna and her seven sons is also sung and told at Hanukah because it is said that her martyrdom in defense of her faith was remembered by the resisting Maccabees. Legend also tells that Hanna was the name of the mother of the Maccabees. THE FEAST The legend of the miracle of the oil has inspired centuries of traditional culinary creations using oil in the cooking process, leading to the burmuelos (the fried dough of some Sephardi traditions), the latke (the potato pancake of Ashkenazi tradition), and a myriad of other traditional treats from Jewish communities from all over the world. THE SEPHARDIM The word “Sephardim” comes from the Hebrew word “Sepharad,” which is found in the Old Testament (Obadiah 1:20) and is thought to refer to the Iberian Peninsula. Historically, Jews who came from that region have been referred to as “Sephardim.” The Sephardim were expelled from Spain in 1492 and from Portugal in 1497. They had inhabited the Iberian Peninsula for at least 1500 years, certainly from the time of the fall of the second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 C.E. Under a reasonably tolerant Moslem reign, the Sephardim achieved a “Golden Age” (900 – 1050 C.E.), a spectacular cultural renaissance in poetry, mathematics, medicine, linguistics, cartography and philosophy. But after having been a vibrant and integral part of the cultural and political environment of Spain for fifteen centuries, the Inquisition systematically forced conversions and destroyed the tangible treasures of their culture. Synagogues and libraries were razed, personal possessions were plundered. These conditions forced waves of emigration which climaxed in the Edict of Expulsion in 1492. The exiled Sephardi travelled to safe harbors, most to the Ottoman Empire and North Africa, some to Europe, and some even to the New World. In their new environments they managed to preserve both Hebrew and Spanish cultures with astonishing tenacity, until the Nazi onslaught uprooted and destroyed these centers in eastern Europe and the Balkans. THE MUSIC The musical traditions of the Sephardim are as complex as their history, poetics, linguistics and geography. In Spanish poetry and music there were often “intermarriages” between Hebrew, Spanish and Arabic traditions. These “weddings” evolved into new works, both secular and liturgical. Secular texts often functioned metaphorically, referring to spiritual yearning as well as to earthly love. An important part of the repertoire is the collection of para-liturgical songs (not part of the synagogue liturgy) for holidays which were sung by the entire community. Every occasion had a trove of songs – the coming of dawn, birth and death, courtship, bedtime, love and marriage. A favorite genre was the romanza, the epic ballad which told of Biblical heroes and heroines, and of the days in medieval Spain when there were kings and queens, knights and princesses. The women sang them as lullabies and at any festive occasion thereby miraculously preserving an astonishing treasure of literature and music. Throughout the centuries, all the elements of the songs were affected by the cultures of exile, creating a fascinating aural panorama. Judeo-espanol, the medieval Castilian Spanish which the Jews spoke in pre-expulsion Spain and which was already rich in Hebrew, later assimilated Arabic, Turkish, Greek, French and Slavic words. The ballads and poems, while retaining their poetic structures, often reflected their new surroundings. The melodies, already imbued with the traditions of the Moors and the Spaniards, began to resonate with the influences of their new homelands. But the essential Iberian character of the music and of the people remained strong because of the remarkable conservatism of the Sephardim, and their unshakeable affection for their Spanish heritage, even in exile.