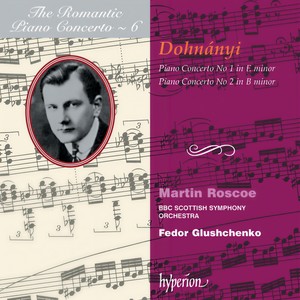

Dohnányi: Piano Concertos Nos. 1 & 2 (Hyperion Romantic Piano Concerto 6)

- 演奏: Martin Roscoe (马丁·罗斯科) (钢琴)

- 歌唱: Fedor Glushchenko

- 乐团: BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

- 发行时间:1993-10-01

- 唱片公司:Hyperion

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:Ernő Dohnányi

-

作品集:Dohnányi: Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 5

-

作品集:Dohnányi: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B Minor, Op. 42

简介

Martin Roscoe携手BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra与指挥家Fedor Glushchenko,共同呈现《Dohnányi: Piano Concertos Nos. 1 & 2》。这张专辑聚焦匈牙利作曲家Ernő Dohnányi两首极具浪漫主义色彩的钢琴协奏曲——E小调第一号与B小调第二号。第一号作品以勃拉姆斯式的厚重织体与李斯特式的炫技交织,展现青年作曲家的澎湃激情;第二号则创作于作曲家成熟期,结构更为凝练,钢琴与乐队的对话充满戏剧张力。Roscoe的演奏精准捕捉了Dohnányi音乐中兼具古典严谨与浪漫诗意的特质,BBC苏格兰交响乐团在Glushchenko执棒下,以丰沛的管弦乐色彩为钢琴声部构筑起恢弘的音响空间。这套录音不仅填补了浪漫派钢琴协奏曲文献的重要拼图,更以当代视角重现了这部被忽视的杰作中深邃的情感张力。