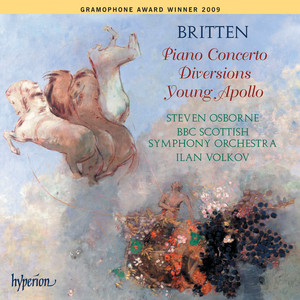

Britten: Piano Concerto; Diversions; Young Apollo

- 指挥: Ilan Volkov

- 演奏: Steven Osborne (钢琴)

- 乐团: BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

- 发行时间:2008-09-01

- 唱片公司:Hyperion

- 唱片编号:CDA67625

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:Benjamin Britten( 本杰明·布里顿)

-

作品集:Britten: Piano Concerto in D Major, Op. 13

-

作品集:Britten: Piano Concerto in D Major, Op. 13 (1938 Original Version)

-

作品集:Britten

-

作品集:Britten: Diversions for Piano Left Hand & Orchestra, Op. 21

简介

The three compositions which comprise Britten’s music for solo piano and orchestra constitute a unique, yet still little explored, part of his output. Here they are brought together in a stunning disc that pays tribute to the great artistry of all involved. Steven Osborne’s performance of Britten’s Piano Concerto with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra under Ilan Volkov at the 2007 BBC Proms redefined this often undervalued work in the ears of his listeners, imbuing it with hitherto unsuspected emotional and musical weight; playing the bravura passages with glittering assurance and joie de vivre. The same musicians have put down a benchmark recording here and, as a bonus, also recorded the original third movement which Britten discarded in his 1945 revision. Diversions for left-hand piano and orchestra is a gem of a piece, which has rarely been recorded. It is highly virtuosic and incredibly well laid out for the left hand, at times almost in the form of études for piano and orchestra. Britten reaches unexpected levels of emotional intensity, most notably in the Chant and the powerful Allegro. Seventy years or so after these works were first performed, their freshness and vitality speaks with the same musical truth that Imogen Holst divined in Britten’s work, when, writing to him after attending an early performance of Peter Grimes, she said: ‘You have given it to us at the very moment when it was most needed.’ In revisiting these unjustly neglected early works, and, through performances of matchless brilliance, discovering qualities that were missed or overlooked when they first appeared, we have good cause to echo her sentiments. The three compositions which form Britten’s music for solo piano and orchestra constitute a unique, yet still little explored, part of his output for several reasons, not all of which are interconnected. As with every aspect of his work they offer a fruitful subject for study; for example, it is fascinating to consider his individual solutions to the challenges each work posed, yet additionally, as a group, they share several characteristics, musical and temporal, which rarely recur elsewhere in his music. But over and above the creative skill and technical mastery which they exhibit stand their expressive qualities—qualities which, as time passes, assume greater significance. As originally conceived, these three works—the Piano Concerto Op 13, Young Apollo for piano, string quartet and string orchestra Op 16, and Diversions for piano (left hand) and orchestra Op 21—were initially written within a period of two-and-a-half years, from February 1938 to August 1940. No other virtually complete genre within Britten’s output comes from such a short period, a period during which the composer found himself writing music almost non-stop (not, in itself, a unique occurrence) and living in different continents. Early in 1939 he had decided to move to the United States with the person who became his life-time partner, in every sense, and most significant inspirer, the tenor Peter Pears. Pears’s influence as a performing artist had already begun to impinge upon Britten, predating and overlapping with these concerto-like works, including the characteristic of display which, in a more obvious but not exclusive manner, they all share. It was not Britten’s initial plan, in the early weeks of 1938, to embark on three such works for piano and orchestra, but—the opportunities having arisen, and in the case of the two later works, the commissions having been accepted—he was clearly stimulated by the different challenges each work posed. As it transpired, he was the third composer in the 1930s to find himself writing two full-scale piano concertos at broadly speaking the same time, in each instance one of those concertos being for the left hand alone. Those other composers were Ravel and Prokofiev. These works of Britten’s do not comprise his entire concerto output, for within the same two-and-a-half-year period he also wrote a Violin Concerto Op 15, and in October 1941 he went on to complete his Scottish Ballad for two pianos and orchestra Op 26. Nor was Op 13 Britten’s first concerto, for in 1932 he had written in short score a full-scale Double Concerto for violin, viola and orchestra, soon after the composition of a String Quartet in D (he revised the latter work for publication in 1975). These two early works, completed as he was on the brink of declaring himself a professional composer, immediately predate his official Op 1—the Sinfonietta for chamber ensemble. The composition of six concerto-like works in nine years at the outset of his career is, at the very least, a serious declaration of intent on the composer’s part. But concerto-like composition was only rarely pursued by Britten during his full maturity, the exceptions being the Cello Symphony Op 68 (1962) and a version for solo viola and string orchestra of Lachrymae, Opus 48a (the original piano accompaniment now orchestrated), which was completed in the last year of his life. In Britten’s early period, the term ‘concerto’ clearly meant something special to him, for—oddly—the Piano Concerto was originally entitled ‘Concerto No 1’ and that for violin ‘Concerto No 2’. Thankfully for us, and doubtless influenced by his publishers, Britten soon dropped this misleading titling. Yet there is another, more important, characteristic—unique in his output and not a little puzzling—regarding Britten’s early contributions to the genre. This is the revision, in one case the withdrawal, of his music after it had been performed, broadcast and even recorded commercially. As a young man, Britten’s music was often criticized for being ‘too brilliant’, ‘too clever by half’, ‘too shallow’, seemingly the product of a supremely gifted composer whose technical ability and inventiveness aroused opposition and criticism that was itself superficial—for the surface vividness of those early scores clearly diverted many from the profundities they contained. No one can deny that in the three works for piano and orchestra (as well as in the Violin Concerto, and more so in the Scottish Ballad) there are many instances of virtuosic brilliance and display—but the central question here is: what was it about these scores that, after they had appeared, caused Britten so much trouble? Surely, if you are that good, why not leave the music to take its chance in the repertoire and get on with the next piece? Why have second thoughts? For it is not as though Britten, of all twentieth-century British composers, was uncertain with regard to the piano (or even the violin); his pianism was greatly admired, even by those who did not warm to his music. He was also a good string player. As a pianist he played concertos and chamber music by other composers publicly and was widely praised as an accompanist (not only to Pears): how odd, we might think, that he would revisit these early works for second thoughts in a way that he didn’t (with one major exception) with his other compositions. In short, what did he think was initially wrong with them, and was he right? This is not the place to attempt to answer that question, yet it remains central to our understanding of his genius. It may be thought that in revising his concertos, Britten demonstrated a characteristic common to all creative figures, that composers are not always the best judges of their own music, nor are they consistently aware of the processes which lay behind their work. Such processes can be demonstrated by analysis which, if well done, may reveal something of the mysteries of artistic creation. Of course, composers at times can be dissatisfied with aspects of their work, in ways they may not be able to put into words, but even then the music—having been freed by the creative process—can exist independently from the creator and exhibit features outside of the composer’s stated objectives which yet appeal to listeners, affording something new and different from the original impetus. Beethoven, of course, is a prime example in that he would disparage several of his own works which later generations have come to regard as being among his greatest masterpieces. Britten never spoke ‘disparagingly’, if you like, of his own music; these revisions—his self-criticisms—are not examples of (taking a phrase from Hans Keller) ‘Functional Analysis’ but of ‘Critical Recomposition’. Britten subjected each of his three works for piano and orchestra to some kind of revision. In the case of his Piano Concerto, we have a completely new third movement, and in Young Apollo the withdrawal of the piece completely from his list of works. Britten began his Piano Concerto in D major Op 13 in February 1938, anticipating a premiere, in which he would be the soloist, at that year’s BBC Proms at Queen’s Hall under Sir Henry Wood. It seems that, from the start, Britten planned a work in four movements. This was certainly a break with tradition, although by no means unique (the most famous four-movement piano concerto is Brahms’s second). But the four-movement form had been tried by other twentieth-century composers, notably by Prokofiev in his second and fourth piano concertos (his fifth is in five movements), and by Shostakovich in his Concerto for piano, trumpet and strings, which received its British premiere early in January 1936 at the Queen’s Hall with Eileen Joyce conducted by Sir Henry Wood. There is no mention in Britten’s published diaries of his being at this premiere, which in the normal course of events he would have attended. So although Prokofiev and Shostakovich had written four- and five-movement piano concertos by 1938, it seems that Britten was unaware of them when writing his concerto, the first performance of which took place on 13 August with Sir Henry conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra. The critical reception was mixed—as one might expect, for this work came as a surprise, even to Britten’s early admirers. In terms of its number of movements, its language and its relationship between solo instrument and orchestra, this concerto was quite different from previous British examples of the genre. During the previous thirty years, only the concertos by Delius (1906) and by Britten’s teacher John Ireland (1930) had shown any likelihood of entering the repertoire. Delius’s Concerto remains the only such work by a British composer to have been played twice during the same Proms season, and Ireland’s had been taken up by a number of eminent international soloists—including Artur Rubinstein and Gina Bachauer. But if the twenty-four-year-old Britten’s work had more in common with Russian or French models, it remains an astoundingly original achievement. The Queen’s Hall audience would have been intrigued—at the very least—by the fact that the work is in four movements, and perhaps more so by the fact that these movement had titles: Toccata, Waltz, Recitative and Aria, and March. Whatever this work might turn out to be, some would have thought, this is going to be a new type of piano concerto for a British composer. The opening Toccata is dazzling in its brilliance, breathtaking in its unstoppable energy: this is music unquestionably by a young composer unafraid to declare himself, grasping his opportunity literally with both hands. This music can only make its full impact if played throughout at the very fast speed Britten demands; the 74 pages of full orchestral score of the first movement alone fly by, the texture and relationship between soloist and orchestra varying this way and that, as if created by some kind of musical magician. Only in the cadenza, where the composer seemingly delights in the keyboard itself, does the speed relax until the secondary thematic group (it is not possible here to speak of traditional first and second ‘subjects’), now combined, enters with soft strings and harp accompaniment to reveal the material in a completely new light before the coda brings the curtain down with a flourish. The quicksilver nature of this music is part of its originality: does any other piano concerto—even Ravel’s for two hands—start at such a speed, or maintain it for so long? Does any other maintain such an unremitting tempo while also unfolding a full-scale sonata structure that embraces a wealth of contrasted ideas all emanating from a single unifying cell? On another level, given the Concerto is in D major, what is the second subject group in the first movement doing in E major, the supertonic? The mixed critical reception the work received at its premiere can partly be explained by the simple fact that the audience had, quite literally, never heard anything like it before. If the notion of ‘display’ inherent in the title Toccata may be thought somewhat ‘un-British’, what of the second movement Waltz, which looks forward to the finale of the Spring Symphony of 1948? Constant Lambert, writing a week after the premiere in The Listener, described this movement as ‘a fascinating psychological study’—probably the first time any music by a twenty-four-year-old British composer had been described in such a way. Lambert did not mention the composer whose instrumentation demonstrably hovers over the music at the close of the Waltz—Mahler—but his insight into this movement was correct (interestingly, Lambert himself conducted the premiere of Britten’s next major work, the choral-orchestral Ballad of Heroes Op 14, in April 1939). In his review Lambert expressed reservations about the Recitative and Aria and the concluding March, reservations that Britten himself came to share (although he was to give three further performances of the original version by the end of 1938), for in 1945 he replaced the Recitative and Aria with a new Impromptu. Fears of a stylistic imbalance in such a juxtaposition are unfounded—despite such masterpieces as the Sinfonia da Requiem, the Serenade, Michelangelo Sonnets and Peter Grimes having appeared in the interim—for the variations which form the Impromptu are based on a theme from incidental music Britten wrote in 1937 for a radio drama on the subject of King Arthur. The essence of the initial musical thought that inspired this new movement is therefore contemporaneous with the original three movements. The revised version was first performed by Noel Mewton-Wood in July 1946 at the Cheltenham Festival with the London Philharmonic conducted by Britten. The original version was not heard again in Britten’s lifetime after he had played it in January 1940 in Chicago conducted by Albert Goldberg—a performance that received rather more critical acclaim than the premiere had done in the United Kingdom. Whatever it was that led Britten to substitute the original third movement with a new one, we can hear the work now in both versions on this recording. In any event, in both versions the third movement leads directly to the concluding March—an extraordinarily extrovert, even ironic (although not satirical) piece in which the semi-tonal germ of the Toccata’s opening idea is transformed into a descending major seventh. The climax of this finale is a cadenza accompanied throughout by an undeviating pulse on bass drum and cymbals—a most original touch. Further references from the Toccata in the coda of the finale enhance the inherent unity of the work. Britten and Pears arrived in North America on 9 May 1939 in Quebec, remaining in Canada for several weeks before travelling to New York State. Less than six weeks after their arrival, Britten had heard the Canadian premiere of his Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge conducted by Alexander Chuhaldin, which seems to have led to his first commission in North America, from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, for a ‘fanfare’ for piano, string quartet and string orchestra. This was Young Apollo Op 16, which Britten himself premiered in Toronto under Chuhaldin (to whom the work is dedicated) on 27 August 1939, followed by a second performance on 20 December in New York. As with the Piano Concerto, both performances of Young Apollo were broadcast; we may hope that, after seventy years, recordings of these broadcasts have survived, but they have so far yet to see the light of day. The title Young Apollo refers to a line in Keats’s unfinished poem Hyperion: ‘He stands before us—the new dazzling Sun-god, quivering with radiant vitality.’ This is as good an image as any around which to create a ‘fanfare’-like work, and Britten’s Op 16 carries the brilliance of the Piano Concerto’s Toccata one stage further, in that it is remarkably monotonal. Indeed, the A major tonality (a key of special significance for Britten in expressing such characteristics) is constant throughout, a fact which has led some commentators to suggest that this was the reason Britten withdrew the work after the second performance (it was not heard again until 1979, three years after his death). But the Sinfonia da Requiem (a work three times the length of Young Apollo) is similarly monotonal, centred upon D, in each of its three conjoined movements, and, moreover, has a triple pulse virtually throughout. In Young Apollo Britten avoids monotony by extraordinary varieties of texture (the utilization of string quartet and string orchestra) and of keyboard writing; he never explained his decision to withdraw the score. Britten’s last concerto-like work for piano is the piece he eventually entitled Diversions Op 21. The repertoire of left-hand piano concertos in the twentieth century came about through the courage of one determined Viennese musician, Paul Wittgenstein, brother of the philosopher, who had been a pupil of Leschetizky. Whilst on active service at the Russian front during World War I, Wittgenstein had lost his right arm. Taken prisoner by the Russians, his condition caused him to be repatriated in 1916, and, back in Austria, he developed his left-hand technique to a very high standard, to the point where he commissioned a Concerto for left hand alone from the blind composer Josef Labor. The success of this work led to three groups of similar commissions from other composers. The first group, commissioned in the 1920s, included Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Richard Strauss, Bohuslav Martinu and Franz Schmidt (Strauss and Schmidt each wrote two concertos for Wittgenstein). The second group, commissioned in 1930, included Ravel and Prokofiev, both of whose concertos were completed in 1931. The last group, from 1940–45 (by which time Wittgenstein had settled in the USA) included two British composers, Britten and Norman Demuth. Wittgenstein premiered all of these works, except for Martinu’s Concertino and Prokofiev’s fourth concerto—he returned the score of the latter to the composer with the comment, ‘Thank you for the concerto, but I do not understand a single note and I shall not play it’. It is clear from this that Wittgenstein adopted a somewhat imperious attitude towards the composers he commissioned. Britten had been warned in advance of the pianist’s bearing, but although discussions between the two men concerning the commission and other aspects of the work were not without friction, it is clear that apart from the financial attraction the composition of the work—once Britten had begun it in earnest, from July to October 1940—came to exert considerable fascination and interest for him. He explained this in a foreword to the publication of a facsimile score in America in 1941, pointing out the attractions of solving the ‘problems involved in writing a work for this particular medium’. Britten’s solutions are many and varied, and cover the entire gamut of keyboard writing, ‘emphasizing’, as he said, ‘the single-line approach’. In this he had more in common with Prokofiev’s approach than with Ravel’s—the Frenchman’s concerto frequently gives the aural illusion of being written for two hands. But Britten’s work does not spare the soloist. The writing is often highly virtuosic and incredibly well laid out for the left hand, at times almost in the form of études for piano and orchestra. Britten revisits the genres of Toccata, Recitative and March from the Concerto, plus those of Adagio, Romance and Chant from the Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge. The close proximity of the composition of these works suggests close musical connections, and one may find a number of them—not so much self-quotation as the use of similar turns of phrase (although in the Burlesque variation Britten quotes from incidental music he had written in 1938 for the play Johnson over Jordan). But following the experience of the Violin Concerto and the Sinfonia da Requiem, Britten probes more deeply in Diversions than he did in the Concerto, most notably in the Chant and the emotionally powerful Adagio. The premiere of Diversions took place on 16 January 1942, with Wittgenstein and the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy. The pianist retained exclusive performance rights for several years, but his autocratic character tended to infuriate conductors and orchestras, and the work was not taken up until the German pianist Siegfried Rapp gave several European performances in the immediate post-War years. Rapp had lost his right arm on the Russian front in World War II, and was to give the posthumous premiere of Prokofiev’s fourth concerto in September 1956 in Berlin. An unauthorized recording of one of Rapp’s performances of Britten’s Diversions had been released in 1953 in America, and although Britten had revised the work in time for Wittgenstein to give its British premiere in October 1950, with the (then) Bournemouth Municipal Orchestra under Trevor Harvey, and had made further final revisions for his own first recording of the work, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra with Julius Katchen as soloist in 1954, these recordings of Diversions—as with the Piano Concerto—did not lead to its entering the repertoire, as those of Britten’s contemporaneous vocal works had done. At one time, Britten’s suggested revisions of Diversions extended to the omission of up to three of the variations, but such drastic pruning has, thankfully, never been observed in performance. Seventy years or so after these works were first performed, their freshness and vitality speak with the same musical truth that Imogen Holst divined in Britten’s work, when, writing to him after attending an early performance of Peter Grimes, she said: ‘You have given it to us at the very moment when it was most needed.’ In revisiting these unjustly neglected early works, and discovering qualities that were missed or overlooked when they first appeared, we have good cause to echo her sentiments. Robert Matthew-Walker © 2008