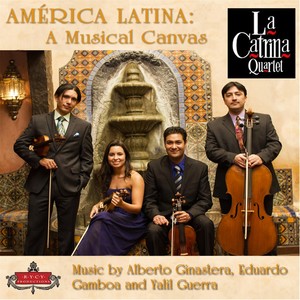

América Latina: A Musical Canvas

- 流派:Classical 古典

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2014-05-16

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

String Quartet No. 1, A Mil Guerras Solo

-

String Quartet No. 2

-

String Quartet No. 1

简介

América Latina. A Musical Canvas La Catrina String Quartet Since its founding in 2007, the La Catrina String Quartet (LCSQ) has become recognized for their place in the vanguard of contemporary Latin American string quartet repertoire. Their mission is three-fold: a deep commitment to the cultivation of new works by living composers from the Americas; the performance of existing Latin American works rarely heard in the U.S. or abroad, and bringing fresh interpretations to classical, romantic and twentieth century masterpieces. Hailed by Yo-Yo Ma as “wonderful ambassadors for music,” LCSQ members are from México (Daniel Vega-Albela, Jorge Martínez-Rios), Brazil (Roberta Arruda) and Chile (Jorge Espinoza). Their origins lend an unparalleled stylistic authenticity and artistic vision to their performances, collaborations and recordings. It is this unique balance of core Latin American repertoire with American and European classical traditions that characterizes both the diversity of their concert programs and appeal to multi-cultural audiences. In 2010, New York City’s Symphony Space, under the direction of Laura Kaminsky, commissioned Puerto Rican composer Roberto Sierra to write his “Cuarteto No. 2” for LCSQ. The quartet’s world premiere was held in 2011 as part of the new music festival “Wall to Wall Sonidos.” That same year they also collaborated with the heralded Cuarteto Latinoamericano for a definitive recording of “Seresta No. 2 for Double String Quartet” by twentieth century Brazilian composer Francisco Mignone. The CD “Brasileiro” featuring the piece won the 2012 Latin Grammy for Best Classical Recording. In October 2014, LCSQ will present the world premiere of a string quartet by Carlos Sánchez Gutiérrez, one of the United States and México’s most prestigious and celebrated contemporary composers, commissioned by the Festival Internacional Cervantino in Guanajuato, Mexico. Recent and future collaborations featuring American composers and artists include Zae Munn’s commission “Our Hands Were Tightly Clenched” as well as a multi-movement string quartet in the making, and a groundbreaking recording of contemporary and twentieth century American music with tuba player James Shearer. To document and distill their efforts as champions of Latin American repertoire over the course of several years and more than five hundred performances, LCSQ is releasing a multi-disc recording project, of which “América Latina: A Musical Canvas” is the first. As Quartet-in-Residence at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, LCSQ devotes a significant part of their educational mission to cultivating and exposing an emerging generation of young listeners to the evolving multi-cultural face of contemporary chamber music through outreach programs. Yalil Guerra (b. 1973). String Quartet No. 1, “A Mil Guerras Solo” Firmly rooted in the twentieth century Latin American tradition of string quartet writing, Guerra opens his first quartet, “A Mil Guerras Solo” or “A Thousand Wars Alone,” with an Allegretto in which he explores the open sonority of stacked fifths across the entire ensemble, writing double stops for each player over a driving motive that alternates with a rhythmic ostinato in the cello, viola and second violin, full of Latin American flair, over which we hear angular melodies exchanged between the violins and the viola. The initial, fifths motive frames this short movement. The second movement, Adagio, explores the expressive possibilities of the full string quartet sound. It is a ballad full of lyricism ornamented by an intricate dialogue between all the voices that creates the feeling of a slow, sensual dance. This is contrasted by a second section where the composer’s melodies and intense harmonies become almost expressionistic in nature, and in the tradition of the Second Viennese School, the movement closes with a deconstruction by way of pointillism à la Webern of the initial introductory material. The third movement, Allegretto, opens with a Mambo call played in unison that serves as the main motive of this final movement which, to this listener, sounds like a rondo quasi una fantasia because of the dreamlike middle sections, in which it is easy to discern the composer’s ear for the visual. Here we also are treated to Guerra’s fascination with the juxtaposition of driving rhythms and variations with lyrical, sinuous melodies that he writes as response to the initial Mambo call. Eduardo Gamboa (b.1960). Cañambú Cañambú is a danzón, one of Cuba and Mexico’s most popular dance forms, in which a slow introduction leads to a second fast section known as a montuno. In the introduction, the choreography, consisting of very small steps, which the dancers execute as close to each other as possible, demonstrates the intricacy and intimacy that characterizes the danzón. It is said that a proper danzón couple ought to be able to negotiate these slow steps successfully on a cinder block without falling off. The slow dance, derived from the European influenced contradanza, segues into a fast, montuno section, itself a variation on Cuban son. This fast, swinging section is characterized by elaborate and virtuosic moves and turns, similar to American rock-n-roll or swing. It is during this section that the danzoneros (danzón musicians) have the opportunity to improvise and display their talent along with the dancing couple. Gamboa conceived this danzón originally for string quartet or string orchestra, and taking advantage of his command of challenging and rhythmically intricate writing, he explored the possibilities that this popular dance form offered to a string quartet, making use of extended techniques such as playing “alla chitarra” (like a guitar) as well as by using various percussive effects such as striking different parts of the instruments in order to imitate the sound of the cañambú (a typical instrument in the percussion section of the danzón ensemble). For the closing section, Gamboa adds a short fugato to this traditional dance, which deviates ever so slightly from the original structure, perhaps as a way of reminding the audience that we are listening to a classical composer’s take on a popular dance form. Gamboa writes, “Cañambú is the name used in Cuba to refer to a certain bamboo cane, different from sugar cane or caña brava, which grows in . . . the Santiago province. In the beginning of the 1940s, sonero (songwriter and performer) Arístides Ruíz came up with a way to use cañambú as a percussion instrument that could replace the bongos. The cañambucero (cañambú player) holds one segment of the cane in each hand, each cane being a different size, thereby achieving both a treble and a bass sound. Holding them in vertical position he strikes them against a small wooden bench. For the [montuno chorus, or reprise] that alternates with the pregones (a pregonero is a town crier represented by the first violin), I used a verse from Alejo Carpentier’s tale Oficio de Tinieblas, which reads as follows: ¡Ahí va, ahí va, ahí va la Lola, ahí va! (There she goes, there she goes, there goes Lola, there she goes!)” Yalil Guerra. String Quartet No. 2 Written in 2014 for LCSQ, this three-movement work uses a contemporary harmonic language, thick in counterpoint and rich textures that require great virtuosity and expressiveness as exemplified in the first movement, Largo e allegro con fuoco. This writing style is common to many of Guerra’s works, where a canvas of hidden Cuban rhythmic patterns and melodic ideas become structural elements of the composer’s musical language. The second movement, Adagio misterioso, is reminiscent of guajiro, or Cuban peasant, chants as portrayed by the first violin through a series of phrases constructed against the backdrop of an ever-changing contrapuntal texture in the remaining instruments, which serves as foundation for the main section of this movement. The quartet closes with an intensely rhythmic Prestissimo in which the composer uses canonic imitation as the template for a recurring rhythmic ostinato that forms the main motive of the movement, which he then contrasts with an equally intense section juxtaposing lyricism against a running, intricately woven scherzando commentary that provides both form and dynamic motion. The ostinato motive serves throughout as material for textural variations, and the movement comes to an exciting finale in which the composer pays homage to Beethoven by citing the “destiny call” from his Fifth Symphony. Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983). String Quartet No. 1 Considered by many to be the foremost Argentinean composer, Alberto Ginastera was part of the last generation of composers of the late Romantic period, one of the most important offshoots of which is Nationalism, a movement that sought to imbue the aesthetic and formal ideals of western classical traditions in music with sounds and rhythms of cultures from throughout the world. Thus, many composers of the time embraced the idea of contributing to the national identity of their countries of origin by compiling, transcribing and studying extensively the native music of their respective homelands. It is thanks to these composers that a new discipline in the study of music came into being, namely, ethnomusicology, which in its broadest terms is the study of the music of peoples of the world. Some of the most famous nationalist composers include Modest Mussorgsky (Russia), Antonín Dvořák (Bohemia), Jean Sibelius (Finland), Ralph Vaughan Williams (England), Bartók and Kodály (Hungary). Ginastera’s String Quartet No. 1 uses as its main compositional materials the sounds and rhythms of the gauchos (Argentinean cowboys) and from the peasants of Las Pampas, the fertile lowlands of South America. This work belongs to Ginastera’s “Subjective Nationalism” period in which, without taking melodies and rhythms directly from Argentinean folk music, he nevertheless relies heavily on them to derive the fascinating sonorities he achieves, much like those that might be heard in the later works of Bartók and Kodály. Thus, the first movement evokes the driving rhythms and open sonorities of gaucho music, and if we allow the mind’s eye to wonder, one can easily picture these South American cowboys riding through the open plains of Las Pampas. The second movement – the most demanding for the players – is a portrayal of a peasant dance called malambo. Traditionally performed by two young men that are coming of age, the dance serves as a rite of passage and is characterized by very fast, aggressive movements. It is a protracted dance intended to allow only one of the young men to remain standing; in essence it is a challenge to the stamina of the contestants. As the movement comes to a close, Ginastera uses his wit to ingenuously depict the victor, which he signals with the cello playing the very last note. The third movement is a sort of Nocturne in which the composer uses the quartet to imitate the sound of the open strings of a guitar – a motive found repeatedly throughout his compositions – as an introduction to the solo violin melody, upon which the cello later elaborates in the middle of the movement. In all likelihood Ginastera composed this beautiful movement to showcase his wife, the prominent cellist Aurora-Nátola Ginastera. The last movement returns to the driving rhythms and sonorities of the first, this time interspersed with long pizzicato sections intended to imitate the sound of guitars. Notes ©2014 by Daniel Vega-Albela