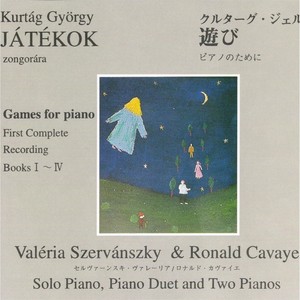

Kurtág: Játékok (Games) for Piano - First Complete Recording Books 1-4

- 歌唱: Valeria Szervánszky/ Ronald Cavaye

- 发行时间:1993-01-01

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

Disc 1

-

作曲家:Gyorgy Kurtag

-

作品集:Játékok (Games) for Piano - Book 1

-

作品集:Játékok (Games) for Piano - Book 1: 73. Hoquetus (For Piano Duet), 74. Perpetuum Mobile, 75. …and Once More

-

作品集:Játékok (Games) for Piano - Book 2

Disc 2

-

作曲家:Gyorgy Kurtag

-

作品集:Játékok (Games) for Piano - Book 2

-

作品集:Játékok (Games) for Piano - Book 3

Disc 3

-

作曲家:Gyorgy Kurtag

-

作品集:Játékok (Games) for Piano Duet & Two Pianos - Book 4

简介

“Játékok” - (Games) by György Kurtág Valeria Szervánszky and Ronald Cavaye perform the following solo pieces. All numbers not listed are for either piano duet or two pianos. Valeria Szervánszky – 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 14-16, 18, 22, 25, 28, 30-31, 34-36, 38-39, 43-45, 47-50, 52, 54, 57-58, 60, 62, 65-66, 68-69, 71, 77-79, 84, 93-95, 102, 104, 107, 114-116, 141-142, 144-145, 147-148, 151, 155, 162, 164-168, 170, 172-174, 176-178, 180-181, 183, 187-189 Ronald Cavaye – 1, 3, 5, 8, 10-11, 17, 19, 21, 23, 26-27, 29, 32-33, 37, 40-42, 46, 51, 53, 55-56, 59, 61, 67, 70, 74-76, 80-83, 85-92, 96-101, 103, 105-106, 108-113, 117-140, 146, 149-150, 152-154, 156-161, 163, 169, 175, 179, 182, 184-186, 190-193 Teaching is of great importance to Kurtág. When he returned to the Liszt Academy to teach after studying in Paris he rejected the idea of teaching composition (which he says he cannot do) and became first an assistant to Prof. Pal Kadosa - the doyen of Hungarian piano teachers. When he eventually became a professor in his own right, he choose to specialise in the field of chamber music rather than the piano as this gave him the widest range from which to study and learn for the benefit of his own compositions. Nevertheless, the piano, remained his chosen instrument, featuring in many of his chamber music compositions. Solo pieces, however, were a rarity - the 8 Piano Pieces Op.3 and the arrangement for piano of the cimbalom piece, Splinters, being the only works from among his early compositions. At the beginning of the nineteen seventies, however, Kurtág began writing a set of very short pieces which were inspired by the spontaneous nature of children at play. When children are left to play on their own they possess the extraordinary ability to enter into and become totally involved in the perfect and fantastic world which they create. This world is both extremely exciting and completely absorbing. A child playing on its own is able to make the fullest use of its imagination. Everything is possible in the world which a playing child creates, and in turn, the created world can take the child over – so much so, that they become oblivious to the adults who call them back for the boring things which have to be done like tidying the room, eating and homework! Fascinating and Wonderful though the realm of a child at play is, for some reason it seems very difficult to preserve these feelings in the study of music. Quite naturally, I write the “study” of music. Music has become another subject like maths or history - something to be studied, rather than enjoyed and lived. When we, as teachers place a child before a musical instrument like the piano, we set him or her a number of tasks. Things must be “learned” and “studied” and “practised” before the next lesson. Indeed it is no wonder that the child feels that music is another “subject” and that he sees little affinity with the wonderful world of play to which he is free to return after the lesson. If we are not careful, a piano lesson can be a very negative experience. The child plays the piece and we, as teachers, immediately begin to correct so many details - the hand position is wrong; there was a misplaced accent in the middle of the phrase; the touch is not beautiful; this was too loud; that too soft. The list of our complaints is endless! Of course, this is how it should be because, as artists, we are always seeking perfection, but such teaching has little to do with the rich world of the imagination created by the playing child. It was to try to recapture something of this spirit of “play” that Kurtág began the composition of Játékok - Games. He started with a few ideas - set out in the foreword to the first four volumes: “The idea of composing Játékok was suggested by children playing spontaneously, children for whom the piano still means a toy. They experiment with it, caress it, attack it and run their fingers over it. They pile up seemingly disconnected sounds, and if this happens to arouse their musical instinct they look consciously for some of the harmonies found by chance and keep repeating them. Thus, this series does not provide a tutor, nor does it simply stand as a collection of pieces. It is possibly for experimenting and not for learning “to play the piano”. Pleasure in playing, the joy of movement - daring and if need be fast movement over the entire keyboard right from the first lessons instead of the clumsy groping for keys and the counting of rhythms - all these rather vague ideas lay at the outset of the creation of this collection. Playing is just playing. It requires a great deal of freedom and initiative from the performer. On no account should the written image be taken seriously but the written image must be taken extremely seriously as regards the musical process, the quality of sound and silence. We should trust the picture of the printed notes and let it exert its influence upon us. The graphic picture conveys an idea about the arrangement in time of the even the most free pieces. We should make use of all that we know and remember of free declamation, folk-music, parlando-rubato, of Gregorian chant, and of all that improvisational musical practice has ever brought forth. Let us tackle bravely even the most difficult task without being afraid of making mistakes: we should try to create valid proportions, unity and continuity out of the long and short values - just for our own pleasure!” Notes by Ronald Cavaye