- 歌曲

- 时长

-

Fantaisie in C Major, Op. 16, FWV 28

-

Grande pièce symphonique in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 17, FWV 29

-

Prelude, Fugue & Variation in B Minor, Op. 18, FWV 30

-

Pastorale in E Major, Op. 19, FWV 31

-

Prière in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 20, FWV 32

-

Final in B-Flat Major, Op. 21, FWV 33

-

3 Pieces for Organ

-

3 Chorals for Organ

简介

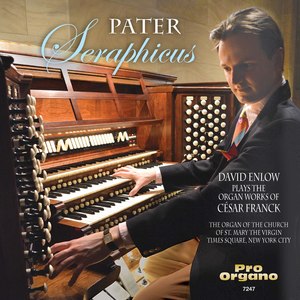

PATER SERAPHICUS PRO ORGANO CD 7247 Digital Audio Producer / Engineer, Post-Production, Mastering, Photographs: Frederick Hohman Zarex / Pro Organo Studio South Bend, Indiana, USA Recorded on 8, 9, 10 May 2011 © Copyright 2011 Zarex Corporation. All rights reserved. PROGRAM NOTES "The organ music of Franck is expressive of warm and deep emotion, of noble grandeur and love, clothed in beautiful melodies and harmonies of an uplifting character. The emotional appeal is not only to musicians, but to all human souls." – Joseph Bonnet, 1942 The Franck organ works, the concentration of that great composer’s considerable powers on the mightiest of instruments, have been much performed, discussed, recorded, and fought over from the time of their publication to our day. In the light of the early music movement and its quest for authentic performance, the works have been approached by some as pure historical recreations, creating renderings which are satisfying only to those who are content when they think they are hearing exactly those stop combinations and manual changes which nineteenth-century French people heard, an impossibility at best and an absurdity at worst. By contrast, others have approached them without any sense of respect for Franck’s character or great expression, and with careless phrasing and ill-considered registration schemes have turned introspective and beautiful works into showpieces for bad taste and poor technique, devoid of nuance and tenderness. Few approach the works with much sensitivity to the original expression, yet take the interpreter’s task seriously and to heart, and develop an original, fresh, musical interpretation. Few combine in their interpretations the poignant lyricism of Franck’s chamber music with the colossal, brooding scale of his orchestral music. Few shine all this material through the lens of the expressive, powerful, modern pipe organ, in order to bring before the public some of the most beautiful music ever written for an instrument with a massive repertoire of beautiful music. That is the aim of this recording. DISC 1 • TRACK 01 Fantaisie in C, Opus 16 • 12:53 This first movement of Franck’s first published organ volume opens in a fitting serenity and calm (C major). The chromaticism of the rest of the Six Pièces and the other organ works is not found in this piece; rather there is, after the seraphic opening, an almost folk-like melody (F minor), which gives way to a fuller, more chromatic passage that relents almost immediately to a closing section on the Voix humaine (return to C major). The piece is ‘fantastic’ in that the various sections are short and highly contrasting, owing much to the Stylus Phantasticus of earlier times. The variety of tone colors sets the example for much of the other music, and the lyrical melody in the middle is one of the passages most reminiscent of Franck’s chamber music. DISC 1 • TRACKS 02, 03 and 04 Grande Pièce Symphonique, Opus 17 • 26:18 Here it is: the first work which likens, in its title, the organ to the orchestra. Organists had been reducing orchestral works to the organ’s resources for at least a hundred and fifty years, but in this work Franck realizes that the instrument’s tonal capabilities, its range of expression, and the scope of the work he has composed for it, are nothing short of symphonic. In the way that the nineteenth-century orchestral innovators such as Berlioz and Wagner broadened the orchestral ensemble, the innovations of Cavaillé-Coll made the organ in France an instrument with infinite variety of sound and expression, like an orchestra, but all under the control of a single performer. It is a height of achievement not to be under-estimated. Oftentimes, organists become over-focused on the imitative orchestral stops in organs of this and other periods and national styles as the defining element of orchestral organ-building, but truly the development which makes the period special is that range and ease of expression by enclosures and stop controls, and the mechanical developments which made them possible, and easy for performers to use. Another canard is the view that this work is the forerunner of Widor and Vierne’s works, which are supposedly built on the Grande Pièce as a foundation. With a few exceptions, the sophistication of thematic unity and tonal scheme is greater in this case than in many of the later works of others. Some of the later organ symphonies are really suites: good music, but not unified in themes and keys in nearly the same way. In the opening, several key centers are explored, including D major and B major, both of which are of significance later on. After this extended introduction, a declamatory (main) theme is introduced in the pedals in the minor of the tonic key of F-sharp (as with much music of the period, the major-minor barrier is diffuse through modal mixture). This theme is worked out and some introduction material returns – and then a small motif from that material is isolated and developed into a running figuration accompaniment to a return of the main theme. This leads to a cadence which paints the tonic key as a dominant. This prepares the ear for the slow movement (Andante) in the sub-dominant of B major. After pages of lyrical melody, the impish ‘scherzo’ (Allegro) begins and develops its own material, and peters out into a lush return of the slow movement music, which is now allowed to end smoothly in its key. Ever desirous of bringing all the themes together, Franck states them in quick alternation – a passage of many swift transitions requiring a subtle and nuanced approach to avoid abruptness. This section having brought all the material of the work to mind, and clouded the ear somewhat, a grand crescendo leads to a triumphant, exultant statement of the main theme in the major, with a running pedal line. Here the tutti sound of the organ is brought to bear, though the final cadence is avoided, in favor of a fugue with an entirely new subject – a surprising but welcome development after the winning and confident homophony of the triumphant section. The theme that brings the work to its climactic close is not the main theme, which has already had its apotheosis, but the new fugue subject, which has appeared, like an ally in combat, to carry the work to victory. DISC 1 • TRACK 05 Prélude, Fugue et Variation, Opus 18 • 11:08 Recording this piece is rather like recording the first prelude of the Well-Tempered Clavier of Bach – a somewhat difficult task which opens one up to criticism from many quarters. This piece is often played by beginning organists as their ‘first Franck’. For the first time in the organ works, the Franck ‘expanding interval’ appears as a major element of melodic construction (figure 1). This technique of beginning with a second or third and expanding the interval is a hallmark of Franck’s melody writing. figure 1 Franck’s gift for melody and form together is in high relief in the piece. Franck writes a beautiful tune with a fugue in the middle, two crafty transitional passages, and an expanded accompaniment for the Variation which imbues the return of the main theme with a renewed interest and complexity. As with a Sonata-Allegro recapitulation, the end of the piece is revised to lead to the tonic rather than the earlier dominant goal. A codetta of great beauty, like a dancer’s closing gestures, draws the piece to a simple, affecting and thoughtful close. DISC 1 • TRACK 06 Pastorale, Opus 19 • 8:48 The great tradition of pastoral music that begins in the Baroque finds its Romantic organ exemplar in this piece. Though it is not as elaborate as the Roger-Ducasse Pastorale, for example, it is formally more cogent and thematically more varied. Here the ‘expanding interval’ is present in its most elemental form, first in the main theme (figure 2) and then in transitional material that leads to the ‘storm’ section (figure 3) figure 2 figure 3 DISC 2 • TRACK 01 Prière, Opus 20 • 14:16 When a piece by a composer already known for heavy introspection bears the title ‘prayer’, the thoughtful interpreter will take notice, and look out for something very special. In this case, there is no disappointment. There are several reasons why this is not as often performed as some of the other Franck organ music. It requires large hands (perhaps the greatest requirement in that respect of any of the works) or for manualiter sections with large spans to be significantly re-written for manuals and pedal. The trouble with that approach is that the shape of the hands when this music is played as written makes certain phrase breaks and articulations almost unavoidable (also the case in the E Major choral, another piece which is often rewritten for ease’s sake) and when it is re-written, those phrase breaks or slight articulations are easily left out. One such is indicated in figure 4, where it is possible, with about five substitutions, to play the phrase legato, but a break is easy and creates a very suitable rhythmic ambiguity over the next couple of measures. figure 4 This complication, it seems, frustrates many performers. Other reasons the work does not appear as often as it should are its lack of ‘flash’ compared to the chorals or Pièce Héroïque, and its significant interpretive challenges. The registration indications are few, and in a sense the piece is a test both of instrument and organist. The organ must have eight-foot foundation and reed tone of enough variety and interest to sustain a piece of considerable length. The performer must find the moments at which he can add or subtract stops subtly to increase the piece’s effect and point up the important moments in the form and phrasing without making certain sections sound like excerpts from a different piece. In this highly chromatic and constantly developing music, one must decide which are the important sonorities, dissonances and melodic high points. Otherwise, the piece can be grandiose, sentimental, or even boring, when it should be the most deeply personal and viscerally affecting of the entire oeuvre. DISC 2 • TRACK 02 Final, Opus 21 • 12:14 The dedication of this piece, to Lefébure-Wély, makes an instant connection with a school of playing which is misunderstood and discounted in our time, a time which favors music that is ‘serious’ to much music that pleases and delights. The style of Lefébure-Wély was very popular in its time, a time in France of one of the great cultural flowerings of history, and his custom was to improvise in concert and church almost exclusively, rather than to perform printed pieces. As Orpha Ochse points out in Organists & Organ Playing in 19th-Century France, we do not know a great deal of the character of Lefébure-Wély’s improvisations, which may have been significantly different from music he put into print. We judge him only by the published pieces, delectable patisseries which may have had more to do with the financial profit to be made by publishing compositions that were very accessible and of varying difficulty than with his making a statement as a composer. It is known that Lefébure-Wély was capable of improvising fugues and extended suites. At the time, Lefébure-Wély was “Prince of Organists” in France, the organist of choice for Cavaillé-Coll dedications and one respected by the public, critics, organ builders, and his colleagues. There cannot have been so much smoke without some fire; we shall never know what the height of his playing was like. The fond dedication (“to his friend, Lefébure-Wély”) also calls into question the idea that Franck and his pupils were the ‘serious’ organist-composers, in opposition to the others, the ‘frivolous’ ones. This dedication is an estimable mark of respect and friendship. In the Final, redolent with enough flair and verve to rival any of the Lefébure-Wély sorties, the opening is a pedal passage with technical dynamism and vigor. The opening theme is contrasted with one of lyrical beauty. Again Franck, in the formal satisfaction of this piece, displaces his contemporaries and some successors; formal sophistication is one of the chief reasons for the pre-eminence of the Franck works. DISC 2 • TRACK 03 Fantaisie in A • 15:36 The Trois Pièces were written for the Salle des Fêtes of the Palais du Trocadéro, a grand exposition building which exists only in photographs, and the plaza and Métro stop of the same name. The ‘Troc’ was the first concert hall organ in France, and its inaugural series produced a sensation in the French capital. Formally more cogent than the C Major fantasy, and musically more nuanced, this fantasy is often called a forerunner of the chorals. It is, surely, but the chorals owe at least as much to the Grande Pièce. This composition is better called the full fruition of the C major fantasy and the Pastorale than an incipient choral. The Fantasy in A, as Rollin Smith tells in Playing the organ works of César Franck, was originally entitled Fantaisie-idylle and had its name shortened before publication. The stalwart main theme, with reeds, is developed and contrasted with a syncopated lyrical theme for foundation stops. A third theme on the Voix humaine emerges (and this feature is a heavy pre-figuring of the chorals) made from new material, which in turn gives way to more development of the first two themes. Unlike the Grande Pièce, in which the ‘combination’ of the themes is achieved by their juxtaposition, this fantasy combines the two warring themes, in a great climax which is preceded by a great chromatic running crescendo – there is no chance of missing it! Having enjoyed combining the two themes, Franck clearly cannot resist inverting them, and the lyrical theme begins again at the top of the pedal board while the first theme is played in octaves in the right hand. Franck made a spectacular entry into the organ class at the conservatoire with a similar device, and the tale as told by Vincent d’Indy (The Century Library of Music, 1900) bears repeating: The competition for the organ prize includes, among other tests, a fugue upon a subject furnished by one of the members of the jury, and an improvisation in a free style upon a given theme. César Franck, having observed that the two subjects admitted of being treated simultaneously, improvised a double fugue in which he [used the] second subject to be treated in free style, thus forming combinations for which the examiners were in no wise prepared. This might have ended badly for him, since members of the jury, for all that it was presided over by the aged Cherubini, understood nothing of this tour de force, accustomed as they were to the methods of the Conservatory, and it was necessary for Benoist, the titulaire of the class, to explain the matter to his colleagues in person, after which they decided to award to the young contestant the second organ prize! If the themes in this piece are characters, or actors, the one who has the last word is the Voix humaine theme, which closes the piece after two fitful, plaintive false starts. Whatever tale these actors have been telling, the end of it is melancholic and final. DISC 2 • TRACK 04 Cantabile • 6:46 A relief from the melancholy of the fantasy, this Cantabile movement gives the organist the opportunity to express the kind of lyricism present in the violin sonata, combined with the power of the organ’s reed stops. With some of the most affecting chromaticism and yet some of the most simple melodic gestures in the oeuvre, this piece’s continued popularity is assured. Franck’s love of canons and skill in their construction and use, ever-present and immortalized in the Panis angelicus from the Mass in A, is at the fore in this piece (having also been present in others) and leads to a chromatic and colorful harmonization of the return of the first theme when it appears in canon. As in many works of Bach, (for example the prelude of BWV 544 and the fugue of BWV 547) the last note of this piece is brief – merely a quarter note with no fermata – a duration which performers ignore at their peril, especially with the extended pedal-tone closing which BWV 547 and this piece share. DISC 2 • TRACK 05 Pièce Héroïque • 9:07 This piece could easily be the soundtrack to a feature film about love in wartime– it is not hard to hear the heroic struggle in the martial character of the opening and the affect which pours from the music of the poignant middle section. With all that character and expression, it would be easy to miss several touches of extremely sophisticated construction. The motive ‘1-2-3’ that opens the piece in the left hand appears in all kinds of chromatic versions, in all kinds of rhythm; this focus on the developing variation of a germ is extremely thorough, and inventive. One interesting point is that the soft middle section material re-appears later, after a generalpause, on the full organ, the apotheosis of a musical character that initially appeared as a meek and temperate theme and has now conquered. In another clever development of material, the ‘timpani’ figure that introduces and sustains the soft middle section, b-f#-b, is transformed into an ostinato which heralds the return of the full organ, and re-appears in its original form at the piece’s splendid conclusion in thundering pedal octaves. DISC 2 • TRACK 06 Choral No. 1 in E major • 15:19 The chorals are Franck’s last compositions before his death, which he likely knew was imminent. Several other composers including Brahms and Liszt turned to the organ in their later days, reaching down to their roots as organists, reaching out to the church or church music, reaching back to the great master Bach, or all three. One must remind the music aficionado who gainsays the organ that many of the great men of music spoke their dying words through it. At this point, Franck had already suffered the injury which probably effectively ended his life, though he had some time for recuperation on his customary summer holiday devoted to composition. The first choral unfolds its themes slowly, and reveals their purposes as they change character through the piece. The opening motive, for example, appears first in simple form, figure 5, then elaborated, figure 6, then as a soft flute interjection, then in simple form as a turgid chromatic passage over a dominant pedal, figure 7, then as a fanfare in the coda, figure 8. figure 5 figure 6 figure 7 figure 8 This is a theme that is explored thoroughly! It is used in so many ways that the effect is one of a great journey through an idea, which finally arrives on the last note in harried victory. DISC 3 • TRACK 01 Choral No. 2 in B minor • 14:36 The second choral is a passacaglia and fugue gone mad. The piece’s opening seems as though variations on a ground bass will provide enough variety and form – and then a second theme enters, seemingly unrelated. No sooner has the second theme had one statement than a third idea comes in, a flowing sixteenth-note lark which has all the whimsy of the Bruckner Gesangsperiode about it, a twittering thing in the midst of a dark, brooding composition. This gives way to a new theme on the distinctive, haunting Voix humaine. Suddenly, the full organ returns with startling passage-work, “con fantasia,” though it is short-lived. Then, on the flat-sixth scale degree, the fugue begins. (On an organ with two oboes, a notorious shared note between subject & countersubject becomes a thing of ease.) Just when the fugue has got underway, the subject is sounded with the earlier second theme on top of it, in E-flat minor, and then in F-sharp minor for good measure! After a working out of the main theme in the tonic, this time with the fugue’s countersubject, the Voix humaine theme closes the piece with its restful cadences, which all agree are sublime. DISC 3 • TRACK 02 Choral No. 3 in A minor • 14:24 The A minor choral is a perfect storm. Franck writes what he knows is likely his very last music, and it contains the most hymn-like of the chorals’ main themes, which is at first beside and then on top of the swirling sixteenth-note figuration which serves as its introduction and accompaniment. With all the hurly-burly of the outer sections, there is hidden at the heart of the third choral the most beautiful melody written for the organ. If this tune had been written for the clarinet in the slow movement of a symphony, it would be in the repertoire of every major orchestra. If it had appeared in a ballet score for the ‘cello playing in the high range, it would be one of the most famous moments in all the world of ballet. If it had been an aria for a soprano in an opera, it would appear on recital programs and arrest theatrical performances with rapturous applause. But it is an organ melody, and so it echoes through churches and concert halls sung by the King of Instruments, and it is spellbinding. The earth-rending close of the choral, following the stupendous combat of hymn and passage-work, is the opening of heaven itself, to ‘Père’ Franck at the close of a great life in music. – David Enlow ***** Acknowledgements and Thanks The artist and the producer wish to extend sincere thanks and appreciation to all clergy and staff at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin for the generous permission to record the organ in their sanctuary, and to Mr. James Kennerley, the Director of Music and Organist at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, for his welcoming kindness and support. Sincere thanks is also extended to Mr. Larry Trupiano, organ technician for the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, for his expert assistance prior to and during the recording sessions, and to people of the Welsh Congregational Church of New York City, for providing a generous grant which supported the production of this recording. ***** Audio Engineering Details: Audio on heard in this product was engineered on location with a MultiChannel DSD® (Direct Stream Digital®) audio recorder made by Genex Audio, Inc., with analogue input signals having a full gain, 0-degree in-phase bandwidth of from 0.25 Hz to 50,000 Hz, obtained from Zarex equipment designed & developed by producer Frederick Hohman. DSD recording offers a sampling rate of 2,822,400 one-bit samples per second per channel, and offers superior performance compared to all existing PCM (Pulse Code Modulation) digital audio recording methods, including extended frequency response up to 40,000 Hertz. Superior fidelity of DSD audio is most apparent in high-definition audio products such as SACD (Super Audio Compact Disc), which uses DSD as its native audio format; however, DSD’s benefits are also evident to discerning ears when multichannel DSD location recordings are mastered and distributed, as with this release, as a conventional CD and downloadable MP3. Leon Giannakeff assisted Frederick Hohman as audio engineer / technician on location. To contact the studio: www.zarex.com To contact the CD label: www.proorgano.com DSD, Direct Stream Digital. Super Audio Compact Disc, SACD and their logos are trademarks of Sony & Philips. ***** DAVID ENLOW David Enlow is widely known as a concert organist of great accomplishment and distinction, both in his native Canada and his adopted homeland the United States. He is Organist and Choir Master of the Church of the Resurrection in New York City where he directs a professional choir. He is a member of the organ faculty of The Juilliard School in New York, and has served as Sub-Dean of the New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists. Mr. Enlow holds both an undergraduate and a master's degree from The Juilliard School where he studied with John Weaver and Paul Jacobs. He also studied at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia and with John Tuttle in Toronto. He is a Fellow of the American Guild of Organists, with the S. Lewis Elmer prize, and an Associate of the Royal Canadian College of Organists, with the Barker Prize. David Enlow has won several national performance competition first prizes including those of the Arthur Poister Competition and the Albert Schweitzer Organ Festival USA. His choir at the Church of the Resurrection performs over fifty mass settings each season, often with orchestra. While in Philadelphia he was Sub-Organist of St. Clement's Church, and he served as an assistant at the famous Wanamaker Grand Court Organ, the world's largest playing musical instrument. ***** The Organ at the Church of St. Mary the Virgin The Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Times Square, was incorporated in the year 1868 in the area of New York then known as Longacre Square. The first church building was located at 226-230 West 45th Street, and contained an unattributed organ which may have been second-hand to the new congregation. This organ was replaced in 1886 by a modest two-manual organ by Geo. Jardine & Son with tracker action and a detached console located in the chancel. In 1895, when the present church building on West 46th Street opened, the congregation was greeted by the sounds of their 1886 instrument, which had been relocated, enlarged and electrified by the original builders. The original portion of the organ was located in a gallery located over the main entrance to the Church; a small Choir Organ was added in the chancel. The organ had two identical consoles, one in the gallery and another in the chancel. However the new Jardine electrical system proved to be problematic. In 1908, the services of Robert Hope-Jones were enlisted to try to rectify the problems. Although improved, the organ continued to be cantankerous till the 1920s. It became apparent to the authorities at St. Mary’s that the time had come for a new organ. G. Donald Harrison, who had recently arrived from England and was in the employ of the Skinner Organ Company, was called upon to make a proposal for a new organ in 1929. Negotiations went on for years, until finally on April 29, 1932, a contract was signed between the Church and the newly formed Aeolian-Skinner Company, Inc. The nucleus of the organ (identified as organ number 891) was contracted for the grand sum of $28,884.00, which included all costs involved with removal and disposal of the gallery Jardine, any and all alterations to the fabric of the Church for the ‘proper’ installation of the instrument, transportation and rigging, and all electrical service required for the new blowing apparatus. The specification of 891 was a solid three-manual organ with a four-manual console (the fourth manual prepared for a Bombarde division) with hefty 16’ 8’ & 4’ French-style Swell reeds for the acoustically rich room. Although there are three known case designs for the instrument, this aspect of the organ never materialized. In 1942, revisions were made to the organ (now 891A), again under the supervision of Harrison. He increased the strength of the Pedal Bombarde unit, installed additional stops on the Great (including the Fourniture and Cymbale), added a 16’ Musette, 8’ Cromorne, 4’ Chalumeau, Gamba and Gamba Celeste, and revised several existing Principals and Mixtures. In the 1990s, the organ underwent a mechanical and electrical renovation by Mann & Trupiano of Brooklyn, NY, who made several tonal additions to the specification during the following decade, always respecting the spirit of Aeolian-Skinner 891A. – Larry Trupiano