- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

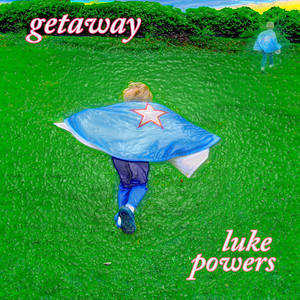

To die a good death means to live one's life. I don't say a good life. I say a life. James Wright “Honey” Luke Powers is caught between trying to bring it all back home and making his getaway. If the title is any indication, it looks like he's leaning toward the latter. His new CD Getaway on Phoebe Claire Records is set for release in August 2009. The college professor and Americana singer-songwriter makes his own visit to the fabled lone country crossroads at midnight. Plays some guitar, sings some songs and takes stock. The devil, in a yellow silk suit and bolo tie, makes a cameo appearance in “Running to Paradise” (the title lifted from W.B. Yeats). But the album as a whole is a more like vision quest. An attempt to reach into the timeless all within the constraints of three-minute songs. An attempt to sing the now into the Now. The songs constitute a mosaic—not an argument so much as a conversation with differing voices. A veritable congregation at the crossroads trying to squeeze some meaning from seemingly incomprehensible experience of the mysterious here and now perpetually vanishing before our very eyes. Or if not incomprehensible, then too often mute. As Powers sings in “The Great Awakening”: “It's not nostalgia, or a memory,/it's just a voice we all hear even if it doesn't always speak.” At times the quest becomes comic as in “Johnny Rotten Come to Jesus Now.” At other times, pure mystery: in the title song “the getaway” from physical to metaphysical is as simple and tangible as striking a match on the grave. On the face of it, “Runaway Drive” is the singer's bluesy elegy to a car peppered with bullet-holes abandoned on the highway side; but the song becomes more about the act of imagining: the singer's thoughts drift to “money, sex and murder” and he wonders, hopes, if vanished couple are still on the run. A similar idea propels “The Real Eleanor Rigby” which does not rewrite the Beatles' classic, but rather turns the table on songwriter Paul McCartney. It offers a version of Eleanor's story (lately come to light due to a hospital record donated by McCartney himself to a British charity) not a tragedy or even triumph. But simply as a life. A life perhaps patronizingly belittled in the famous song. But a life which E. Rigby lived and struggled and died—but maybe not so alone after all. A life. What more can the artist or the humble songwriter confirm? Witness? Admire? “Dahlia”--on the famous “Black Dahlia” of 1940s L.A.--admits into evidence the horrific murder, but bends toward a transcendence of those unspeakable facts. The life vibrating from the famous black-and-white glossy smiling promo photo of the twenty-two-year-old girl. Luke says, “I had nightmares for days after seeing the pictures from Black Dahlia crime scene. I felt compelled to write this song in a feeble attempt right the wrong done her. I wanted to honor the living soul not the tortured body.” There is even a song about math. Lord Hamilton, 18th century discoverer of the “quaternion” or four-dimensional mathematics, is remembered for his “genius flash” in which the famous equation came to him as he strolled by Dublin's Broom Bridge (where he scrawled the notation into stone lest he forget). Is the quest successful? Does the vision cohere? Like life itself, the songs of Getaway are more a set of questions than answers. Perhaps the best answer comes from poet James Wright: But listening back to them, Luke admits: “I've listened to these songs a hundred times during the recording and mixing. But there are still times when I listen where I forget where I am in the song. Just for a moment there's a beat and bass riding and guitars fiddling and fiddles droning and voices humming and a steel guitar singing like another world and you realize you stumbled into something timeless.”