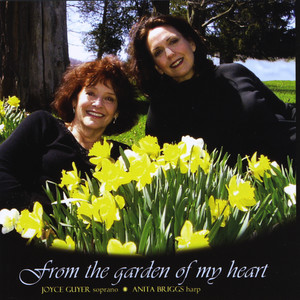

From the Garden of My Heart

- 流派:Classical 古典

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2009-09-01

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

The Artists . . . The two artists on this recording met in Cherry Valley, New York. Joyce was singing the role of the Countess in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro with the Glimmerglass Opera. Anita and her husband, Walter, being big fans of opera, rented the cottage on their property, Willow Hill, to opera singers during the summer festival seasons. Joyce Guyer has been a featured soloist at the Metropolitan Opera for sixteen seasons as well as five seasons at Bayreuther Festspiele (Germany). She sang leading roles for summer festivals in Central City (Colorado), Glimmerglass (N.Y.), Buxton (England) and Catania (Sicily). She worked with eminent conductors James Levine, Sir Colin Davis and many others. She has often been a featured artist on worldwide broadcasts sponsored by Texaco, NPR and PBS. Ms. Guyer is presently on the faculty of the University of Washington teaching Voice since Fall of 2007. Recent engagements include faculty recitals (Florida State University, U. of Washington in Seattle), featured soprano soloist in Brahms’ Requiem (Monterey Symphony, Master Chorale of South Florida in Fort Lauderdale),Verdi’s Requiem (Valdosta Symphony), Bach’s Christmas Oratorio (St. Cecilia Society in Carnegie Hall) and Haydn’s Creation (Akron Symphony). Anita Briggs studied with legendary harpist Carlos Salzedo. She has served as principal harpist with New Haven, Amarillo, Macon, Columbus and San Angelo Symphonies, Boston Ballet and Hartford Opera. She worked under Nadia Boulanger and Paul Hindemith, and recorded with the Atlanta Choral Guild. She plays frequent recitals and chamber music concerts. Her book of harp solos, “Odyssey,” is published by Lyon and Healy. For this recording, Ms. Briggs has transcribed and transposed the songs for the harp from the original piano-vocal scores. Composers and their music . . . Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) “We should always remember that sensitiveness and emotion constitute the real content of a work of art.” -Ravel The Cinq mélodies populaires grecques were selected from Greek folk melodies and set between 1904-1906. (Published in 1909). The critic M.-D. Calvocoressi, who was of Greek descent, commissioned them and provided Ravel with French translations. Ravel played the role of “musical herbalist, by harmonizing them, giving flavours and fragrances to the existing folk melodies. Le Réveil de la mariée is a mixture of fancy and intoxicating humor. We hear a gentle but insistent prodding from the bridegroom as he awakens his bride. Là-bas vers l’eglise portrays bell-like clarity, an atmosphere of “doleful grandeur with great economy of means.” The deliberate and proud monody in Quel gallant m’est comparable? is introduced by a slender chord, then the declamation that is reminiscent of ancient traditions where boastful men recount their tales, referring to more than just the pistols that hang below their belts. The fourth song, Chanson des cuelilleuses de lentisques, mingles melancholic and sober images of women’s swaying bodies working in the fields. The last song, Tout gai! is a flighty, dancing agile mood, alternating between 2/4 and 3/4 rhythms. What brings this performance a particular charm is the timbre of Brigg’s harp transcriptions that clarify the colors of the harmonies. These arrangements add an authenticity that would be difficult to achieve on the piano. Claude Debussy (1862-1918) “Music and poetry are the only two arts that move in space” (Debussy) Debussy was a genius at finding the spaces between the notes, but his early songs did not yet incorporate all that he would eventually do to bridge tonal music to atonal. (whole tone and pentatonic scales, foreground chromaticism and indeterminate key centers). The songs on this recording are from his youth and they reflect the simplicity and innocence of a more straight forward nature, an unfolding young genius. These songs are shaped more like those of Fauré. Nuit d’étoiles (Banville,1823-1891) was Debussy’s first published, but not first composed song at age 18. (1880). The naiveté of awestruck innocence mixed with sadness is felt in the clarity and simplicity the singer’s interpretation and the harp’s celestial shapes create mixed feelings of peace and melancholy over lost loves. Fleurs des Blés (cannot yet find dates of poet Girod), is innocent and joyous. Beau soir (Bourget, 1852-1935), probably written in1883 , is the epitome of text painting and unlike the other two songs in this set that are ABA form, this is through-composed. Languid but insistent waves lap against the shore. This is really a “holding one’s breath” kind of music because it goes beyond the text to create a vision of our own ultimate return to the source. The Harpist Composers . . . There are twelve years difference in the ages of the two “Marcels.” Marcel Lucien Tournier (1879-1951) and Marcel Grandjany (1891-1975). Both shared many of the same experiences in their education and in their contributions to the respective fields of performing, teaching and composing. But unlike Tournier who remained in France, Grandjany left to live in the United States where he eventually became a U.S. citizen. Tournier was friends with Ravel and his work was also deeply influenced by Debussy, Nadia Boulanger and Fauré. Other harpists of influence on his work include Lily Laskine, Carlos Salzedo, Micheline Kahn, Pierre Jamet and Henriette Renie. Grandjany, the younger composer, began harp studies early (age eight) and was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire at age eleven. He and Tournier both studied with Hasselmans. As well as being a harpist, Grandjany was a professional organist engaged at Sacre-Coeur. After moving to the United States, he continued giving concerts. As a teacher, he was chairman of the Julliard School of Music, and on staff at many other prestigious schools including the Manhattan School of Music and Montreal Conservatory as well as teaching privately. He played his final recital in 1967. Grandjany’s technique was sensuous, enhanced by his large, spatula-shaped fingertips. His pieces for solo and ensemble are acclaimed for their idiomatic and archetypal beauty for the instrument. As a teacher he established a method that was used worldwide, sharing this distinction with his colleague, Salzedo. There still exists strong rivalry between proponents of these two methods in the field of harp pedagogy. Ms. Briggs was a student of Salzedo and follows in his tradition. Tournier developed the double-action Erard pedal harp which allowed for many new and innovative compositions, tonal possibilities and exploration in pedal glisses, sliding chords, simplified glissandi, synonymous note combination and enharmonics. This composer/performer has given harp repertoire a great legacy in the exploration of new capabilities for the harp that encouraged a new kind of music. La lettre du jardinier (Bataille, 1872-1922) resembles an operatic scene from Massenet (1842-1912) in its declamatory style and beautiful soaring phrases.Theatrical aspects of the work shine in this duo with sensitive and rich parts for harp and true operatic declamatory style sung by one who knows this genre and its subtleties. This is perhaps the most moving piece on the recording as it captures a bitter sweet longing of such direct, yet elegant emotion. The song, O bien aimée, from Verlaine’s (1844-1896) text was also set by Fauré in his collection La bonne chanson (original title of the poem is La lune blanche luit dans les bois). Grandjany’s setting is more extraverted, and was originally set for baritone voice. It premièred on the occasion of a wedding of friends of the composer. Dramatic changes in harmonies between verses and a solo interlude for the harp after the second stanza, reflects beautifully the meaning of the text in this scene of adoration. It is a rich contrast to Tournier’s letter scene that resembles more an operatic szene than a song. Floating and passionate phrases lift Grandjany’s song giving it a joyful and adoring mood. Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Ravel wrote that “It is truly in his songs that Fauré offers us the flower of his genius.” Others called him a “Master of Charms,” the one who dominates the history of the mélodie. Fauré began his studies at the École Niedermeyer. This school’s approach to composition emphasized study of the harmony at that time but also a study of church modes. These modalities incorporated new colors into his writing, which was quite unlike the music of his predecessors’. One of Fauré’s best interpreters, Claire Croiza wrote, “His songs are tender, yet virile, never sentimental. They shine with a light that is spiritual as well as physical; perfectly balanced and aristocratic in the best French sense, discreet and serene, but full of underlying passion.” Interpreting a Fauré song is to be free from any need to interpret. This is because there is no moulding necessary as might be the case in German Lied. The “smoke, mirrors and prisms” are all within the musical language. Aurore Op. 39 No. l, (Silvestre, 1837-1901) from the year 1884, is the earliest composition of this group and rocks us gently between the G major homophonic A section to g minor in the B, and back to G major. The accompaniment in the B section is a gentle arpeggiated movement possibly painting the text where one feels the beginning of the new dawn and life. Following this simple opening and magical mood, are four of Verlaine’s poems set to a rich contrast of musical ideas. En sourdine Op. 58, No. 2, and Prison Op. 83, No. 1(1894) both have that measured tread in the accompaniment, allowing the vocal lines to unfold steadily overhead in variegated arches. Mandoline Op. 58 No. l, (1891) followed by the “immortal” Clair de lune (1887), a true menuet and maybe his greatest song, make this CD worth everything one could wish for in the true sounds of the poetry. Brigg’s transcriptions capture a magical vibrational field that no piano ever could. It is the strings and the perfect plucking that create overtones. Both introductions to these two songs are breathtaking and the singer continues the mood with effortless spun out lines of creamy tones. Liza (Elizabeth Nina Mary Frederica) Lehmann (1862-1918) was born in London. Coincidentally, she has the same life dates as Debussy. A soprano and composer, she was fortunate to have artistic parents. Her mother was a teacher and composer and her German father, a painter. She studied both singing and composition and although she had a wide vocal range, it did not include power enough to make an operatic career. Therefore she concentrated on recitals. Composition studies took her to Rome and Germany as well as studying in her homeland. When she retired from singing in 1894, she married a painter and composer, Herbert Bedford. In a Persian Garden, appeared In 1896 as a collection or cycle of selected quatrains from Edward FitzGerald’s (1809-1883) version of the Rubãiyãt of Omar Khayyãm. It was originally scored for four solo voices with piano. This presents an added challenge to the singer, for there are four voice types designated to sing the different songs. The exotic texts and lyrical style of these pieces appealed to contemporary taste and became quite popular. Although some of Lehmann’s works are now regarded by some as fossils of this period’s taste, many of her compositional procedures remain fresh and have been undervalued. These songs fall in the same époque as the French language groups, but they contrast greatly with the French mélodie. The closest of the French songs to Lehmann’s style would be Tournier’s Lettre du jardinier.” Lehmann’s first four songs remind one of parlour music popular in the United States as we may hear in some of the songs of Amy Beach or even Charles Ives. The texts are well represented in each individual setting. But the essences of each song is that of a romantic character piece. The exception is the last one, Ah moon of my delight. It reminds one much more of Puccini’s lush harmonies and surely could have flourished on the musical theater stage had the composer been in a position to devote her career to it. But, she leaned more to furthering the English morality genre, and another coincidental connection to Debussy occurs where her somewhat austere essay, Everyman, appeared on a double bill with his L’enfant prodigue.