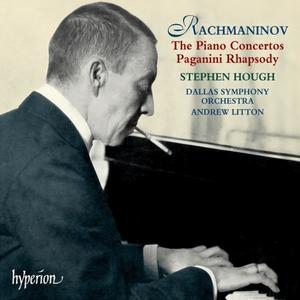

Rachmaninov: The Piano Concertos & Paganini Rhapsody (拉赫玛尼诺夫:钢琴协奏曲 & 帕格尼尼狂想曲)

- 指挥: Andrew Litton (安德鲁·利顿)

- 演奏: Stephen Hough (霍夫) (钢琴)

- 乐团: Dallas Symphony Orchestra (达拉斯交响乐团)

- 发行时间:2004-10-01

- 唱片编号:CDA67501/2

- 译名:拉赫玛尼诺夫:钢琴协奏曲 & 帕格尼尼狂想曲

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:Sergei Rachmaninoff( 谢尔盖·瓦西里耶维奇·拉赫玛尼诺夫)

-

作品集:Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 1( 升f小调第一号钢琴协奏曲,作品1)

-

作品集:Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 1

-

作品集:Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Minor, Op. 40( g小调第四号钢琴协奏曲,Op.40)

-

作品集:Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Minor, Op. 40

-

作品集:Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini, Op. 43

-

作品集:Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43

-

作品集:Rhapsody on a theme of Paganini, Op. 43

-

作品集:Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 18

-

作品集:Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 18( c小调第2钢琴协奏曲,作品 18)

-

作品集:Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 18

-

作品集:Piano Concerto No. 3 in D Minor, Op. 30

简介

Ever since we started working with Stephen in 1996 recording these concertos has been on the agenda: it’s probably been the project closest to his heart. But it took several years before we found the orchestra and conductor that we felt would do justice to this important project. The combination of Dallas and Litton offers a conductor who adores Rachmaninov (he has recorded all the symphonies) and understands the works from a pianist’s perspective, an orchestra with a glorious and old-fashioned string sound of the kind with which the composer would be familiar, a hall to record in which is one of the best in the world, and let’s not forget Stephen Hough who has already won two Gramophone ‘Record of the Year’ accolades for his concerto recordings. As the results here triumphantly show, all our hopes have been fulfilled, and more. Apart from the ‘Paganini Rhapsody’, recorded after a concert performance, these are essentially ‘live’ recordings. Over a period of eighteen days eleven concerts were given, with each concerto being played several times. From these we have pieced together an ‘ideal’ performance—free of coughs, noises and the few musical mishaps which occurred, but still capturing the excitement of what was, by common consent, a sensational series of concerts. These days a new recording of the Rachmaninov concertos has to be very special for it to be worth doing at all and it was not lightly that Hyperion proceeded with this project. Stephen’s very conscious return to the fast and lean performance tradition of the composer himself, avoiding the sentimental ‘Hollywood’ approach that has become so prevalent, coupled with the supreme level of the performances themselves has truly created a Rachmaninov cycle for the new millennium! That Rachmaninov’s official opus 1 should be a piano concerto would seem only natural for one destined to achieve colossal fame as a pianist-composer. But his path to that fame – as indeed to that first concerto – was far from straightforward. It was marked on the one hand by severe life-challenges, and on the other by seemingly limitless creative prowess; and the piano concertos are the most vivid and enduring monuments to the tension between these extremes. Rachmaninov’s background was a privileged one. His father and paternal grandfather, both of them musically gifted, had army careers. His mother was the inheritor of five country estates, one of which (near Novgorod, about one hundred miles south of St Petersburg) was the future composer’s childhood home, where he and his brothers and sisters were educated by private tutors and governesses. Seemingly also marked out for an officer’s life, the young Sergei Vasilyevich soon displayed musical gifts sufficiently startling to persuade the family to invest in piano tuition from a graduate of Petersburg Conservatoire (one Anna Ornatskaya). Meanwhile, by dint of extraordinary improvidence, his father was squandering the wealth he had come into, and at the age of eight Sergei had to move with his family to a crowded flat in St Petersburg, he himself winning a scholarship to study at the Conservatoire. A diphtheria epidemic carried off one sister; Sergei was infected but survived. In due course his father left the marital home, entrusting the children to his wife’s care. The previously rather conscientious student fell into chronic laziness and at the age of twelve failed all his non-musical examinations. In the same year his older sister Elena, whose singing voice had inspired him and who was about to join the Bolshoy Opera in Moscow, died of pernicious anaemia. Salvation from potential despair and what might have become a wastrel’s life came, but at a price. Rachmaninov’s mother appealed to his cousin, the Liszt pupil and famous conductor-pedagogue Alexander Ziloti, to audition the young musician; Ziloti’s recommendation was the notoriously harsh regime of his own former teacher, Nikolay Zverev, at Moscow Conservatoire. Zverev took Rachmaninov into his house, charging nothing for board and lodging, and providing not only tuition but also tickets for concerts, operas and the theatre; the quid pro quo was unquestioning submission to the prescribed regime of practice (supervised by Zverev’s equally stern sister), not excluding corporal punishment for less than total diligence. All the same, this was a cultural education as well as a pianistic forcing-house. On Sundays Moscow’s great and good would call at Zverev’s house and hear his pupils perform (they were nicknamed ‘cubs’, because the root meaning of zverev is ‘beast’), spurring their ambition and bringing an aura of wisdom and cultivation. The Conservatoire itself housed a galaxy of musical talent at that time, with luminaries such as Tchaikovsky, Arensky, Taneyev, Ziloti and Safonov mingling with rising stars of the calibre of Busoni, Scriabin, Goldenweiser, Lhévinne and Igumnov. The Zverev regime was enlightened enough to allow for theory tuition, in preparation for further study with Arensky. The teenage Rachmaninov progressed to Taneyev for counterpoint (with Scriabin as fellow-pupil) and to Ziloti for piano. At the age of sixteen a painful break with Zverev ensued, over a bungled request for more privacy. This led to his rehousing with an aunt and four cousins (one of whom he would eventually marry) with the family name of Satin. Their summer estate at Ivanovka, southeast of Moscow, would become a haven for composition until Rachmaninov left Russia at the end of 1917. By his own admission, laziness continued to feature in his makeup, particularly in his studies of counterpoint and fugue. But by now his own piano miniatures and songs were beginning to flow, along with more ambitious works, many of which are now lost. Piano Concerto No 1 in F sharp minor Op 1 Rachmaninov was not quite eighteen when he began work on his First Piano Concerto. At the time he still had a year of Conservatoire study ahead of him, during which his tasks would be to compose his first opera and his first symphony, these being Arensky’s conditions for accelerated graduation. The symphony would in fact be delayed several years, but Tchaikovsky’s support for the resulting opera (Aleko) led to publishing agreements and a rapid opening-up of professional opportunities. The first documented mention of the Concerto seems to be on 26 March 1891, in a letter to another of his numerous cousins, and its completion followed on 6 July, after a month of near-solitude at Ivanovka. Rachmaninov compensated for his ongoing lassitude, or so he claimed, by composing the second and third movements in a two-and-a-half day burst, working from five o’clock in the morning until eight in the evening. The score carried a dedication to Ziloti. Rachmaninov performed the first movement at a student concert on 17 March 1892, in the Small Room of the Hall of Nobility. On that occasion the student orchestra was conducted by Vasily Safonov – by then Director of the Conservatoire – who was used to making corrections and cuts in his students’ work. This time, however, Safonov found himself bowing to the will of the fledgling composer. It is not entirely clear when, or even if, Rachmaninov played the work in its entirety (though others certainly did so) before he shelved it for revision. It was to be September 1917 before he finally got round to that task. Rachmaninov set the finishing date to the revised score on 10 November, just weeks after the storming of the Winter Palace and the enthronement of the Bolshevik regime, whose baleful effects he would flee six weeks later (though he had been laying plans even before the October Revolution), never to return to Russia. He first performed the new work on 29 January 1919 in New York with the Russian Symphony Society Orchestra, conducted by Modest Altschuler. Rachmaninov was an inveterate rewriter. But he took the red pen to his First Piano Concerto more radically than to any other of his works (the case of the Fourth Concerto runs it close). The central tutti of the first movement and the first half of the cadenza were newly composed, and the finale was just as extensively recast. Among the excised material was much that openly declared a debt to Grieg’s Piano Concerto. That model can still be detected behind the opening orchestral fanfare and pianistic flourishes. This is an amplified version of Grieg’s straightforward tonics and dominants, Nordic candour traded in for Slavonic melodrama. The orchestra then launches into one of Rachmaninov’s signature swooning lyrical themes, immediately picked up by the piano. Still shadowing the Grieg Concerto, the piano continues with darting figurations, before giving way to another orchestral song-theme. The largely sequentially constructed development section with rhapsodic breaks, the piano-led reprise, and the hypertrophic cadenza all fall into the pattern established by Grieg. But the devil is in the detail, and especially in its revised version this movement asserts its individuality by means of its ecstatic waywardness. One of Grieg’s closing slow movement ideas supplies Rachmaninov with the opening of his comparatively modest Andante. This is marked by the piano’s improvisatory dreaminess, the quintessence of Romantic rhapsody: healing, as it were, all past longings and allowing the hero of the Concerto – the music’s personality, mediated by the soloist, with which we are invited to identify – to shake off the fetters of the past. Rachmaninov’s instinct for decorative passagework and for inspired harmonic deflections and balancing returns shines through. Now only the final cadences remind us of the music’s Griegian paternity. Concerto finales are by tradition brilliant, physically exhilarating affairs, which is one reason why the symphonic scherzo is usually dispensable. This finale is no different. But perhaps compensating for the fact that the opening ideas are flashy and rather empty, it is the lyrical second subject that brings the movement into focus. Once again it is Rachmaninov’s genius for variation and renewal that keeps the structure alive, rather than any deeper-lying compositional strategies. And by 1917, when he was putting the Concerto into its definitive shape, he was unrivalled in his ability to ratchet up audience excitement over the last pages. Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 The path between Rachmaninov’s first two piano concertos, from his late teens to late twenties, was scarcely less stony than the one that had preceded the first. On the positive side, he was developing significantly as a conductor, reckoning that he could hardly do worse than Glazunov. He landed a post with Savva Mamontov’s private opera company (where the young Chaliapin was also making his mark), and conceived the best of his three short operas, Francesca da Rimini, for it (although completion of that work was to be much delayed). Other than that, however, he was scratching a living from various less than prestigious teaching posts. Feuds at the Conservatoire involving Ziloti, to whom Rachmaninov was staunchly loyal, ruled out a post there. It is from this stage that the famous scowl seems to have become etched on his face. Creatively there were more setbacks than triumphs. Rachmaninov’s dissatisfaction with what he had achieved in his First Concerto was as nothing compared to the trauma that ensued from the 1897 premiere of his First Symphony, distorted as it was under the baton of a reportedly less than entirely sober Glazunov. This was compounded by the more or less routine self-doubts of the young professional musician and by the ongoing tendency to existential listlessness, worthy of a character from Rachmaninov’s much-admired Chekhov. Two visits to the elderly Lev Tolstoy, designed to inspire the young composer, had more or less the reverse effect. At the first the revered author offered merely banal imprecations to daily toil (Tolstoy was by this stage well into his own self-despising phase; he had gone native and was tilling the soil on his estate at Yasnaya Polyana). At the second visit, in the company of Chaliapin and Goldenweiser, Rachmaninov had to endure Tolstoy’s withering response to his music, which was to echo down into the days of Soviet Socialist Realism: ‘Who needs it?’. After his London debut at the Queen’s Hall on 7 April 1899, Rachmaninov was invited to play his First Concerto the following year. Instead, however, he promised to compose ‘a second and better one’. But with his spirits at a low ebb, that was easier said than done. Famously it was a visit to a friend of a friend (and a near neighbour) of his aunt and cousins that changed everything. Dr Nikolay Dahl was a music-loving doctor who had taken an interest in therapeutic hypnosis – all the rage at the time in France. Psychological malaise being endemic in Russian society, Dahl found plenty of scope for practice, and his results were reputedly impressive. Probably the successful therapy in Rachmaninov’s case had as much to do with conversation with a cultured man who turned to music for consolation as with actual hypnotherapy. At any rate the Second Concerto was released from the composer’s blocked psyche. In gratitude he dedicated the concerto to Dahl (who as an amateur violist would sometimes even play in the piece, garnering applause when his identity was disclosed). That at least is the official version of events, deriving from Rachmaninov’s own autobiographical notes. However, one family report runs rather differently. According to the composer’s grandson, Alexander, who claims to have been told the story by his grandmother and sworn to secrecy until fifty years after her death, the true reason for Rachmaninov’s visit to Dahl was to court the doctor’s daughter, who was the secret inspiration behind the Second Concerto and who remained a shadowy presence during the composer’s subsequent married life. Alexander told this story to Stephen Hough in person; as yet there is no independent verification, and Rachmaninov scholars regard it with scepticism. Whatever the true background, Rachmaninov’s creative inertia was overcome, and during the summer of 1900, spent largely with Chaliapin in Milan, he put his ideas for the new Concerto in order. He composed the second and third movements back in Russia and performed them on their own on 2 December in Moscow’s Nobility Hall, with Ziloti conducting. The two cousins would collaborate eleven months later on the first complete performance of the Concerto at the Moscow Philharmonic Society. It was not until May 1902 that London heard the work promised them three years earlier, and a further six months went by before the composer himself played it there (early British performances were given with Ziloti and Basil Sapelnikoff as soloists). Anyone not knowing that the first movement was composed last might reasonably assume that its famous solo piano opening was the seed-idea for the whole work. This dark-hued progression, with its steady chromatic ascent and bell-like reinforcements in the bass, reappears in various disguises at nodal points in the work: as the closing harmonic progression of the first movement, at the beginning of the second, and, most obviously, just before the first main theme of the finale (after the piano’s opening flourishes). As in the First Concerto, the first movement exposition follows a Griegian pattern, the two main ideas, both of them now gorgeously lyrical, being spaced by brilliant figuration. The central phase, as before largely built on sequences, manages to sound freshly invented while adhering rigorously to existing material. There is no cadenza. Instead the structure unfolds as an unbroken, perfectly proportioned symphonic whole – no question of revision being needed this time. The interweaving of soloist and orchestra is a constant marvel, as is the scoring itself. As the Concerto’s popularity grew, so its themes were treated to numerous song settings and arrangements, including the slow movement as Prayer for Violin and Piano by Fritz Kreisler ‘in collaboration with the composer’. The basic arpeggio figuration here comes from Rachmaninov’s early Romance for six hands at the piano, composed just after the original version of the First Concerto. The design echoes the slow-fast-slow pattern made famous by Tchaikovsky in his B flat Concerto, though in Rachmaninov’s case the faster music emerges gradually, as if under pressure from the internal force of its lyrical motifs. Just as the slow movement raised the curtain with a magical modulation to E major from the first movement’s C minor conclusion, so the finale returns to C minor by stealth from the end of the slow movement. Once under way, the finale unfolds another drama of emotional turmoil, longing, regret and tussles with Fate, all the while blending the rhapsody and virtuosity of the Lisztian concerto tradition with the rock-solid craftsmanly values Rachmaninov learned from Taneyev. Another unverified story behind the Second Concerto has it that Nikita Morozov (a fellow graduate from Arensky’s composition class in 1892, and the same Morozov who criticized the structure of the first movement and nearly plunged Rachmaninov back into creative self-loathing) actually composed the finale’s beautiful second melody and, on hearing of his friend’s admiration for it, allowed him to borrow it. In 1946, three years after Rachmaninov’s death, this would become the hit tune ‘Full Moon and Empty Arms’. And among films that featured extracts from the Second Concerto were Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955) and David Lean’s Brief Encounter (1946), the latter brilliantly matching the music to a scenario of emotional triumph longed-for but probably only achievable in fantasy (a scenario perhaps closer to the origins of the piece than previously imagined, if the story told by the composer’s grandson has any basis in reality). Piano Concerto No 3 in D minor Op 30 Between the composition of the second and third concertos Rachmaninov married his cousin, Natalya Satina – not before getting the necessary dispensation from the Tsar. Despite a number of serious ailments, including bouts of angina, and the pressures of a young family, his three-pronged career as composer-pianist-conductor advanced on all fronts, creating problems by its very success. He completed Francesca da Rimini, composed a further opera (The Miserly Knight), and fulfilled a temporary conducting contract with the Bolshoy Theatre so successfully that he was offered the post of musical director there, as well as taking charge of orchestral concerts. In 1906–7 he wintered in Dresden, largely to avoid the temptation to conduct and instead to forge ahead with composing his Second Symphony and his First Piano Sonata. At this stage still much exercised by financial worries, he had the confidence-raising prospect of a lucrative American tour as pianist, for which he had in mind a third concerto. This work was largely composed in the summer of 1909 at Ivanovka, though its conception probably goes back two or three years before that, and it was finished in Moscow that September. It was dedicated to Josef Hofmann, who, however, never played it. Rachmaninov practised the fiendishly demanding solo part on a dummy keyboard during his Atlantic crossing, before giving the premiere on 28 November 1909 with the New York Symphony Orchestra under Walter Damrosch in New York’s New Theater. The American critics were not yet disposed to rave about Rachmaninov as a composer, even though, or perhaps because, the reputation of his C sharp minor Prelude preceded him, as it had done ten years earlier in Britain. After the premiere the New York Sun declared, ‘sound, reasonable music, this, though not a great nor memorable proclamation’; and in general the best the press had to say about the Third Concerto was that it put the Second in the shade. Rachmaninov for his part took badly to what he saw as the pervasiveness of the American business ethic, and despite thunderous audience acclaim he found the American public cold. Nineteen days after the premiere, he played the new concerto with the New York Philharmonic under Gustav Mahler at Carnegie Hall, professing admiration for the Austrian maestro’s attention to detail and his ability to make the musicians stay on, unprotesting, long after the scheduled end of a rehearsal. On 4 April 1910 he introduced the concerto to Russia, with the Moscow Philharmonic conducted by Evgeny Plotnikov. Russian critical responses were warmer than those of their American counterparts, but in general European critics considered the work more as a splendid vehicle for Rachmaninov’s pianism than as a noteworthy composition in its own right. Even so, only a few years later the Third Concerto’s success had become so colossal that even as self-confident a spirit as Prokofiev was intimidated by the piece and determined to outdo it with his even more gargantuan Piano Concerto No 2. The D minor Concerto opens with a sense of palpable anticipation; anyone bar the first-time listener knows that this modest pulsation is going to unleash waves of astonishing power and energy. The opening paragraphs are in a constant state of becoming. The strings are kept muted while the tempo accelerates, and ideas spin off that will germinate further on – such as the trumpet counterpoint that will soon support the second subject, on strings alone, before the piano is sent into dreamy raptures by it. Once again the ability to rhapsodize without sacrificing tautly disciplined thematic working brings to fruition everything Rachmaninov had learned from Taneyev and, indirectly, from Tchaikovsky. The remainder of the exposition is again built on a series of accelerandos. And all this is but preparation for the colossal accumulation of the development section. This initially dips down, gathering energy for the ascent, and in its course Rachmaninov goes through a bewildering succession of different keys while maintaining unwavering control of their overall trajectory (regulated by the bass line on cellos and double basses, from the breakthrough climax to the entry of the cadenza). Among his second thoughts for streamlining the piece were to provide the first movement with a less densely packed cadenza than the original (Stephen Hough plays this revision, as does the composer himself on his single recording of the work, made with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy in 1939–40). After its titanic climax the cadenza enters a relaxation phase, supporting snippets of the opening theme on flute, oboe, clarinet and horn in turn, and the movement concludes with a brief review of all the material, the last few bars marked accelerando, in conformity with the main structural principle established in the initial phases. As in the Second Concerto, the slow movement starts by bridging the harmonic gap from the previous one. This process is greatly magnified, and once again the main ideas are all in a greater state of tonal flux than their counterparts in Rachmaninov’s previous concertos. Does the soloist’s opening flourish – rooted on F sharp minor with added sixth – define the home key, as it thrusts away the orchestra’s continuing attachment to D minor? Or is its subsequent descent into D flat major the defining moment? (Rachmaninov’s notated key signatures tell their own story, interestingly at odds with the music’s surface orientation.) A hyper-passionate climax seems to purge the movement of its expressive longings, and a mercurial F sharp minor episode fleetingly recalls the main first movement theme, now woven around the piano’s repeated-note figurations. Now that the piano has temporarily got the urge to rhapsodize out of its system, it pushes through to a mini-cadenza, which serves as a characteristically hyperbolic upbeat to the finale. Music as firmly rooted in tradition as Rachmaninov’s always draws on the vast stock of archetypes inherited from the nineteenth century, skirting the edges of allusion and quotation. But the opening paragraph of the finale is closer than anything else in the Third Concerto to outright quotation, paraphrasing as it does Rimksy-Korsakov’s Russian Easter Festival Overture. This reference in turn lends support to those who would trace religious imagery in the work back to its chant-like opening theme (a connection that Rachmaninov himself always brushed aside as fortuitous, despite his own devout Orthodox nature, and despite being steeped in the Church’s musical traditions). A foretaste of the heroic victory to come, built on the piano’s galloping left-hand syncopations, eventually subsides into a long chain of episodes, initially fairly relaxed but gradually building into a vast accompanied cadenza (which the composer significantly cut when he made his recording). This central phase is cadenza-like both for the pianist – in its swirling toccata figurations – and for the composer – in its subtly crafted references back to the first two movements at the same time as it works over the finale’s own ideas. As with the Second Symphony, the finale features a redemptive wide-spanning theme, with piano and orchestra at last united in a paean of praise to an unspecified higher power. Piano Concerto No 4 in G minor Op 40 Composer’s block is a relatively recent phenomenon. Its roots – like so many in the history of music – may be traced to Beethoven. But so far as the extraordinary creative silences that afflicted Sibelius, Elgar and Rachmaninov are concerned, it would be difficult to find any parallels before 1918. It hardly takes a PhD in social history to see why that date should be significant. The Great War dealt a terrible blow to European cultural self-esteem, and the ethos of the Roaring Twenties, plus the triumph of new commercial means of dissemination, reinforced it. Now the kind of lyrical self-expression that had previously seemed self-evidently valuable suddenly became not just unfashionable but positively vulgar and repellent. Faced by the expectations of audiences tired of romantic effusiveness, many composers who had reached creative maturity around 1900 either had to redefine their aims or fall silent. Rachmaninov had composed some forty major works before leaving Russia for ever after the November 1917 Revolution; but he managed a mere half dozen in the twenty-six years from then until his death (and not one of these was completed during his first nine years abroad). The dual culture-shock of exile from his beloved homeland and more general post-war trauma undoubtedly played a part in this hiatus. ‘I feel like a ghost wandering in a world grown alien’, he wrote. ‘I cannot cast out the old way of writing, and I cannot acquire the new. I have made intense efforts to feel the musical manner of today, but it will not come to me.’ There were more mundane factors in addition. In America, cut off from the relatively privileged lifestyle he had so painstakingly achieved, Rachmaninov had to begin a new career as an international concert pianist in order to provide for his immediate family (and in due course to subsidize an increasing number of more distant needy relations and friends). The demands of a rapidly expanding repertoire, together with the rigours of travel and recording, squeezed out any spare time that might have been devoted to composition. In 1926 he finally succeeded in taking a sabbatical year away from performance in order to complete his Fourth Piano Concerto. Ideas for this work had been taking shape since 1914, and he had even withheld from publication one of his 1911 Études-tableaux (for piano solo) probably because he had already formed the intention to rework its second half as the closing section of the concerto’s slow movement. Putting his ideas for the new concerto into shape proved to be fraught with difficulty, in part simply because Rachmaninov had to relearn the habit of composition, in part also because he was sufficiently influenced by the spirit of the times to have become suspicious of his own natural grandiloquence. (His concerns may be judged from the cuts he inflicted on his Third Concerto and on his Second Piano Sonata in its 1931 revision.) Hardly was the Fourth Concerto complete than he began trimming it. One-hundred-and-fourteen bars were shorn off in the summer of 1927, following the tepidly received first performances (given with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy), and a further seventy-eight bars disappeared in summer 1941, just before Rachmaninov recorded the work with the same artists. The result of these vacillations is a work that seems ridden with doubt. On the one hand it has one of the most inspired opening gambits in the entire concerto repertoire, the piano entering on the crest of a wave; and the proportions of the first movement are subtly adjusted throughout, so that grand statements ignite suddenly, rather than having to go through the motions of elaborate rhetorical build-up. Yet the final bars of this movement are strangely throwaway, while the slow movement hovers indecisively between expansive statement and the modesty of an interlude. As for the finale, it constantly shies away from the Dance of Death character that seems to be its main thrust. For these and other reasons the Fourth Concerto has been much maligned over the years. The inevitable, though not necessarily more enlightened, reaction is to ascribe all such criticism to prejudice or narrow-mindedness. A subtler judgment might be that the music’s insecurities and vacillations are precisely what give it its potential appeal to post-modern sensibilities. And there can be little doubt that Rachmaninov’s late masterpieces – the Paganini Rhapsody and the Symphonic Dances – would have been inconceivable without its example. The Concerto is dedicated to his friend Nicholas Medtner. Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini Op 43 For all Rachmaninov’s struggles with the structure of the Fourth Concerto, its composition at least reminded him what it felt like to be creative. 1928 saw the publication of his Three Russian Songs for choir and orchestra and in 1931 he composed the solo piano work generally known as the Corelli Variations, although its theme is one that Corelli himself had merely borrowed from the stock-in-trade of Baroque techniques. The Corelli Variations also drew their share of critical flak, and Rachmaninov himself had doubts about their merit, routinely omitting a number of variations each time he played them, according to the amount of coughing in the audience (as he wryly observed to Medtner). But they form another significant precedent for his next major work, the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, composed in 1934 at his then recently purchased lakeside villa near Lucerne. The Rhapsody takes another commonplace idea from musical history and plays more or less serious games with it. And although the game-playing aspect is by no means the only fascinating feature of this work, its more general significance is enormous. It enabled Rachmaninov to be confident in his creative vitality, in that he could now return to the musical language he had left behind nearly twenty years previously, without being constrained by its associations with grandiloquent emotionalism. In effect he could now step outside his own musical persona and let it assume all sorts of roles, from old-fashioned poetic confession to a smart urbanity no more than a whisker away from Gershwin. The theme itself comes from the last of Paganini’s Twenty-four Caprices Op 1 for solo violin. This unobtrusive yet wonderfully suggestive pattern of flicking upbeat motifs had already captured the imagination of Liszt and Brahms, and it would continue to inspire composers after Rachmaninov, as diverse as Witold Lutosl/awski and Andrew Lloyd Webber. Rachmaninov’s first game is to place the theme – on the strings with the piano picking out salient notes – after the first variation. And that initial ‘variation’ – on pizzicato strings following a general clearing of throats for orchestra and piano – is itself already something of a game, since it makes a pun with the finale of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony (which likewise introduces a skeletal version before the theme itself). Now that the work is properly under way, Variations ii to vi start to split the elements of the theme apart and to recombine them into new musical personalities. The pauses and rhetorical flourishes for the piano in Variation vi herald a change of tempo and tone. Next the piano gravely intones the head-motif of the Dies irae – the medieval ‘Day or Wrath’ plainchant from the Mass for the Dead – while the orchestra accompanies with the opening motif of the Paganini theme. The Dies irae was a favourite of Rachmaninov’s, and its apocalyptic associations are by no means irrelevant even here. Still, the combination of ideas is a kind of musical game, and one that will be played out later in the Rhapsody. But not immediately. In Variation viii the piano reinstates the fast opening tempo and leads off with determined staccato chords. This is another musical pun – an in-joke even. The motif is still Paganini’s, but the shape and gesture are taken straight from Glazunov’s Sixth Symphony, which the twenty-three-year-old Rachmaninov had arranged for two pianos. The piano and orchestra’s confrontational chords continue to accumulate, until the Dies irae bursts through again on the piano’s low octaves in Variation x. Another general pause ensues, and the piano’s scale and arpeggio flourishes in Variation xi herald a new slow phase. Variation xii is in the tempo of a minuet, with the Dies irae motif once again more to the fore than the Paganini theme. Back in the main Allegro tempo, Variations xiii to xv form a kind of scherzo, the last of the three variations being initially for piano alone. Variations xvi and xvii become ever more shadowy, continuing the sequence of key-changes that began with No xiv and setting the stage for the famous Variation xviii. This glorious lyrical outpouring, based on an inversion of Paganini’s main motif (a sublime piece of game-playing this!), was already a legend in its composer’s lifetime, at least as early as 1939 when Fokine choreographed a ballet to the Rhapsody and – apparently with Rachmaninov’s collaboration – reintroduced the big tune as an apotheosis at the end of the work. The last six variations make a dazzling finale, with piano, orchestra and composer going through increasingly virtuoso paces, and Rachmaninov’s last game-like gesture comes with the throwaway final cadence. In another sense, the very last of Rachmaninov’s games is actually the title he eventually settled on, having considered and rejected the perfectly appropriate ‘Symphonic Variations’ and the less happy ‘Fantasia’. For this Rhapsody is one of the most tautly constructed, least rhapsodic works he ever composed, and at the same time one of the most disciplined and inventive (not to mention thrilling and sensuously beautiful) sets of variations ever composed. David Fanning © 2004