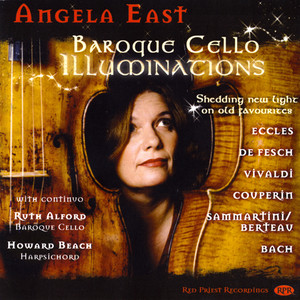

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

Sonata No. 11 in G Minor

-

Sonata in D Minor, Op. 8 No 3

-

Sonata in D Minor, Op. 8 No 3

-

Sonata No. 5 in E Minor, RV40

-

Pieces en Concert from Les Gours Reunis

-

Sonata Op. 1a, No 3 in G Major

-

Suite no. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007

简介

East is throwing light on the missing element in much baroque performance: the performer. Rubato, extreme dynamics, rhythmic variation generate the excitement of spontaneity. Classical Music ‘Recording of the Fortnight’ Not only a joy to listen to with gutsy playing (from East you would expect little else) these are piece used to teach cello students so this disc has a good educational value too.....a fine disc of cello music. Early Music Today She makes music which can sometimes sound merely intellectual and academic genuinely affective...her performance (Bach Cello Suite No 1) deserves to be ranked with the best, (Pierre Fournier and Paul Tortelier) MusicWeb International A nice disc of ‘old favourites cello teachers like to teach.’ All despatched with style and conviction and a good model for cello students everywhere. Musical Pointers Angela East plays with all the verve and technical mastery of one of the world’s finest baroque cellists. New Classics Listening to this CD is like greeting an old friend you haven’t seen for ages. So much is warmly familiar it makes the heart glad and slightly nostalgic. I have never before heard a recording of the de Fesch Sonata in D minor, for instance, which I remember playing in my distant school days. And yet there are embellishments and delicate ornamentation that give an exciting freshness to the interpretation and promise that revisiting these old friends will be very worthwhile as there is more to discover. This CD takes treasured favourites firmly away from being pieces used simply on a learning pathway to over an hour of glorious Baroque played on period instruments. European String Teachers’ Association Magazine exciting and imaginative ....I particualrly like the ornamental embellishments on the repeats in the Eccles [and] dramatic effects in Vivaldi's Sonata. The Strad When the early music movement began in the late 1960s, a new dimension opened up for the study of baroque music. Players were looking to use instruments in original condition or modern reproductions; musicologists were studying original manuscripts and discovering that modern publishers were producing fairly inaccurate representations of what composers actually wrote. Most importantly, the pioneers researched historical performance techniques. A few publishers made urtext editions from original manuscripts and old editions, some of which are quite illegible or covered in ink blots. The composer might have made mistakes or could be unclear about where slurs began and ended. All of these problems needed interpretation by an editor, producing diverse results. Original instruments were altered at the beginning of the 19th century when modern concert halls created a demand for increased volume. Necks were angled, creating more tension on the strings and the bass bar and other pieces of wood inside the instrument were replaced by larger pieces. The fingerboard was raised and higher bridges were made, so that the string tension was greater, creating more volume. A new bow was designed by François Tourte to play with equal strength in both directions. Composers could then write long melodic lines suitable for the Romantic era. The burgeoning of the early music movement saw the restoration of instruments to their original condition, played without the modern supports of end-pin, chinrest or shoulder rest. These supports affect the angle of the bow and left hand to the strings which in turn change the mode of most technical procedures. Pitch, rhythm, dynamics, vibrato, tempo, note-lengths and phrasing have all changed in meaning over the ages. The mood or ‘affect’ was a priority in baroque music, whereas quality of tone was the be-all and end-all for the Romantics. Gut strings, essential for playing on a baroque instrument, were used, ironically, by nearly everyone until the 1960's when players gradually changed to metal. In spite of its sensitivity to climate and humidity, gut is more flexible and produces a different and more subtle range of nuances, especially when combined with the convex baroque bow, giving stronger down bows and neutral up bows, ideal for dance music. A knowledge of the history of performance practice, together with an appropriate instrument and a good edition are the basic requisites but only the communicative skills of the performer will bring the music to life. HENRY ECCLES junior1675-85 – 1735-45/FRANCESCO ANTONIO BONPORTI (1672-1749) Sonata no 11 in G minor transcribed from the violin sonata. Second movement borrowed by Eccles from Bonporti Op. 10 no 4, 4th movement Henry Eccles came from a very large Eccles family with more than one Henry in it, so assuming we have the right one, he was a violinist and composer who moved to France in 1713, possibly to live permanently. His dates are uncertain; 1671-85 for his birth, to 1735-45 for his death. Theft and impersonation were common in those days and from this set of twelve violin sonatas, published in Paris in 1720, he borrowed 19 movements from Valentini’s Allettamenti per Camera. In Sonata no. 11, the second movement is borrowed, not from Valentini but from the second movement of Bonporti’s Sonata Op 10 no 4. The glorious opening sixth makes this piece particularly adaptable from the violin version, as the use of register on the cello automatically creates a different colour. The first movement is intensely lyrical and that inspired me to add plenty of ornamentation to the continuo cello part as well as my own. The borrowed second movement is marked ‘Stacato and Alegro’ (spelled like this). This leads into an Adagio via a harpsichord transition, which is utterly operatic, like an aria that is sung after the death of a loved one. In order to convey the tragic element of this movement I decided to play it with very little ornamentation. The final movement is marked Presto, not Vivace as in the modern publications. I created my interpretation from the 1720 edition published in Paris by Foucaut, Gregoire and Eccles himself, dedicated to M. le Chevalier Gage and signed by Eccles. Bonporti’s compositions were designed as a means to promote his real career as a priest in Trent in the Dolomites. Having completely failed to secure any promotion by this means, he moved to Padua where he died in 1749. He learned the violin with Corelli. WILLEM DE FESCH (1687-1757?) Sonata in D minor Op 8 no 3 A violinist, already with a formidable reputation at the age of 13, Willem de Fesch lived in Amsterdam 1710-25. From then until 1731 he was Kapellmeister in Antwerp but eventually fell out with the authorities, owing to his ‘temperamental, mean and slovenly nature’. A few years later he moved to London where he stayed for the rest of his life. Here he befriended Frederick, Prince of Wales and first son of George II. Frederick was anti-Handelian, largely because his parents, whom Frederick resented for deserting him in Germany as a child, were great supporters of Handel. Frederick was a cellist, so presumably de Fesch wrote his 30 cello sonatas for him. De Fesch had many opportunities to play and compose in London but it was not until 1746, after having had an argument with Frederick, that he became first violin in Handel’s orchestra. His Op 8 contains twelve sonatas, of which this Sonata no 3 is considered to be the height of his development. He wrote them in 1733 and they show the changes in his development that had taken place over the previous few years in Antwerp. They were written and published in London. ANTONIO VIVALDI (1678-1741) Sonata no 5 in E minor RV 40 Antonio Vivaldi was born in Venice in 1678, shortly after an earthquake had struck the city. He took after his father, both in the colour of his hair, which was red and in his post as violinist at St Marks. His clerical and musical careers ran side by side, being ordained and appointed Maestro di Violino at the Pio Ospedale della Pieti in the same year, 1703. His successful training of the orphaned girls there led to his redundancy in 1709, and although he was invited back with promotions, he was eventually fired because of conduct unbecoming of a priest. As a musician he has been described variously by writers of the time as ‘wild and irregular’, ‘too routine’, ‘volatile and to misapplication of good parts and abilities’ and his music as having a ‘peculiar force and energy’ He received more praise for his violin playing than his composition, for example Uffenbach, who described his playing thus: ‘he came with his fingers within a mere grass-stalks breadth of the bridge, so that the bow had no room’. His 90 odd sonatas are more conservative than his 500 odd concertos but they contain interesting elements such as syncopations, chromaticism and Lombardic rhythms. He varied the 6th and 7th degrees of the scale, using the augmented 2nd as a melodic interval such as in the first movement of this sonata. On the repeat I have varied the effect by playing the melodic minor scale followed in the next bar by a poignant D natural. Vivaldi’s nine sonatas for the cello and basso continuo were published in Paris in about 1740. In the fifth sonata the opening bars somehow do not fit into the rule-governed baroque style to which one has become accustomed, whether the notes are played long or short. Long notes sound too romantic, so I decided to make them ultra-short and piano. These, and the canonic effect, invite both attention and curiosity about the way the piece will develop. Much of the interest in the repeat depends on the ornamentation I have added to the continuo rather than my own part. In the Allegro I have used as much variety of bow-stroke as possible and have taken the liberty to change the rhythm in the accompaniment in bars 3-6 and 34-36 to create more drive. The third movement, Largo, is relatively simple but I have used strummed chords in the second cello part the first time and ornamentation and double stops in my part on the repeats. In the last movement I aimed for spiky notes at the start to give it character, with lots of contrast between the fortes and pianos and their corresponding bow-lengths throughout. The pause four bars before the end, as in the Bach Gigue, invites attention for the ending, which can otherwise appear to be very abrupt. FRANÇOIS COUPERIN LE GRAND(1668-1733) Pièces en Concert from Les Goûts Réunis arr. Bazelaire/East I originally learnt these pieces as a child but upon taking up the baroque cello, it struck me as a pity that arrangements like these would be forever disallowed by the early music fraternity because they are not as originally written and have been adapted for the cello rather than the more appropriate viol. French cellist Paul Bazelaire (1886-1958) published the set of five and I have rearranged La Tromba and La Plainte myself. François Couperin, ‘Le Grand’, descended from a vast family of farmers. The Couperins were also the principal musical figures in Paris for about 250 years and for 173 of those were organists at the church St Gervais. François, 1668-1733, organist, harpsichordist and composer, was the most important member of the family. This set derives from Les Goûts Réunis which Couperin wrote in 1724. He was not specific about the instrumentation of his pieces but just gave suggestions about the possibilities. On the frontispiece he wrote ‘à l’usage de toutes les sortes d’instrumen de Musique.’ The fleeting ornamentation and asymmetrical gait in the Prelude are typical of French style whereas the Siciliène has a wonderfully flowing direction. La Tromba is a reference to the instrument called the tromba marina which was long and triangular with one string, played in harmonics. I therefore decided to include as many harmonics as possible in my version and in addition, wrote a little introduction and matching mini-coda. Originally written for two viols, the Plainte relies on a drone, so I decided to provide this myself by playing pedal harmonics. The Air de Diable, as one might expect; has fast semiquavers interacting with those on the harpsichord, to bring the set to a wicked close! GIUSEPPE SAMMARTINI (1695-1750) /MARTIN BERTEAU(1700-1771) Sonata Op 1a no 3 in G major First published 1748 Paris Academics and cellists alike have had a lot of fun trying to identify the composer of this sonata, no 3 of two identical sets of six that exist in the British Library, one by Sammartini, the other by Berteau. Which of several possible Sammartinis is also a mystery. The sonata sounds like the work of two composers of different nationalities. I have supposed that it was either collaboration or a borrowing of one from the other and have tried to work out when the composers could have met each other. The most likely Sammartinis, the famous oboist brothers Giovanni Battista and Giuseppe, were prolific composers. Giuseppe travelled to London in 1728, so could have met Berteau in Paris whilst travelling there, whereas Giovanna Battista spent his whole life in Milan. On the other hand, Martin Berteau 1700-71, father of French cello playing, travelled to Italy to hear the famous cellist Franciscello, so could have met either of the brothers then. The bustling first movement is in sonata form with elaborate developments towards the end. There are a number of pause points that allow for cadenza-like material, mostly written by the composer. As the frequency of these moments increases towards the end of the movement, I have chosen to treat the whole of this section as a cadenza, with plenty of rubato. The second movement is rich, very passionate and full of double stops and the third is a hair-raising gigue. Then there is a complete change. The plethora of harmonics and the extremely mannered rhythm in the last movement demonstrate clearly a French origin to anyone familiar with this style. JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH(1685 – 1750) Suite no1 in G major BWV 1007 Bach thought that he was in the happiest period of his life when he wrote his six solo cello suites. He was working for Prince Leopold in Cöthen, who for once was someone who ‘loved and understood music’ (Bach’s words), who sang and played the violin, the viola da gamba and the harpsichord. There were 18 instrumental musicians employed by the time Bach moved there in 1717, which provided him with ample opportunity to write chamber music, notably the Brandenburg Concertos with their different instrumentations. Sadly this happy position was not to last, because when the Prince married in 1721, his wife’s lack of interest in music influenced him adversely, so Bach decided to move on to Leipzig. Luckily he wrote his solo violin and cello music just in time. Although the cello suites were supposedly written for Prince Leopold who was an amateur cellist, the actual secret dedicatee is more likely to have been Christian Ferdinand Abel, (father of the famous viol player, Carl Friedrich Abel) for whom Bach commissioned two instruments, one with four strings, the other with five, required for the sixth suite. The source material from which I worked mostly was the facsimile by Bach’s second wife, Anna Magdalena, whom he married one week in advance of the Prince’s wedding in 1721. Analysis of the paper and handwriting indicated that she copied the suites sometime between 1727 and 1731 for one of Bach’s pupils. Her slurs are so inconsistent that I have chosen to take her as literally as possible apart from the addition of a few improvised slurs of my own. Copyright Angela East 2009 Born into a musical family, Angela East, began tuition at the age of four; at fourteen was awarded the Arts Council’s prestigious Suggia Award to study with Muriel Taylor. She then went to the Royal Academy of Music to study with Derek Simpson and afterwards with André Navarra and Christopher Bunting. In 1979, after a number of years of performing on the modern cello, Angela was inspired by the new early music movement to acquire a baroque instrument. She became co-principal cello with the English Baroque Soloists under Sir John Eliot Gardiner and with this orchestra she performed in some inspiring venues: La Scala Milan, the Sydney Opera House, the Carnegie Hall, the Palace of Versailles and the ruins of Pompeii. She was invited to play as a continuo player and soloist with many of the foremost baroque orchestras in London including the first performance on original instruments at Glyndebourne with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment under Sir Simon Rattle. In 1990 Angela founded the multi-instrumental ensemble, The Revolutionary Drawing Room. This ensemble made eight CDs of Boccherini and Donizetti String Quartets for CPO records, one of which was chosen by Stanley Sadie in Gramophone magazine’s ‘Critics’ Choice’. The ensemble performed in a number of important international festivals such as those in Ottawa, Stuttgart and Leeds. In 1997 she became a member of baroque group Red Priest, which has given several hundred concerts in many of the world’s most prestigious festivals and in most European countries, Japan, Australia and throughout North and Central America. Angela gives regular recitals; one of her programmes is entitled ‘A Tale of Five Cellos’ in which she plays the viola da gamba, the bass violin, the baroque cello, the five-stringed cello and a cello of 1828. Angela has a long history of teaching private pupils, a number of which are now professional players themselves. She has contributed articles to Early Music Today magazine, various newsletters and has published her own editions of the Donizetti String Quartets. She has performed many times on radio and television, including Open University programmes and has made over 200 CDs. She was awarded an ARAM for her distinguished services to the music profession in 1994. www.angelaeast.co.uk Ruth Alford thrives on a broad musical diet from Baroque to Contemporary, whilst sharing her enthusiasm for music through various educational outlets. She performs and records widely throughout Europe , Far East and America as a principal player and continuo cellist with the English Baroque Soloists , Orchestre Révolutionaire et Romantique and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment as well as chamber ensembles including the Brandenburg Consort, the Revolutionary Drawing Room, the Music Collection, Fiori Musicali , Florilegium, Configure8 and the Chamber Players. Howard Beach’s uniquely wide-ranging style of keyboard playing has been developed through many years of partnering top musicians in a gamut of different fields, including recitals, recordings and broadcasts across the world, in duo with Piers Adams, work as piano accompanist to several well-known singers and as harpsichordist with Les Arts Florissants. A truly transatlantic musician he shares his name with an infamous suburb of New York.