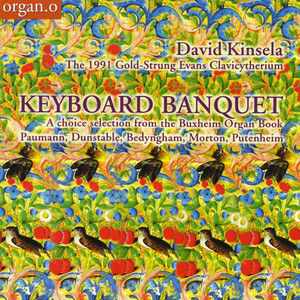

- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

Keyboard Banquet is a choice selection from the Buxheim Organ Book attributed chiefly to Conrad Paumann (c1410-1473). This is a banquet hosted by the ducal family Wittelsbach of Munich after the mid fifteenth century, at the eve of modern times. Vainglorious kings afford an indulgence rarely seen since classical Rome while humanist scholars of Greek, Arabic and Hebraic declare ever louder that all are equal before God. Magic yields slowly to realism, feudalism to individualism, marital possession to chivalrous romance. Modern keyboard art was founded through the shared creative efforts of patrons, instrument-makers and keyboard-players right across Europe. The String Keyboard Modern keyboard art was founded through the shared creative efforts of patrons, instrument-makers and keyboard-players right across Europe. The earliest successful stringed keyboard instrument, the chekker or eschequier, a development of the monochord, appeared in history when the kings of England and embryonic France lived in the same city from 1357 to 1360. Being the first portable keyboard playable by both hands, it led to the notation of keyboard music and thus to the start of a written repertoire (CD Fundamentum ORO202). By 1400 the chekker had developed into two types of string keyboard. The clavichord 'keyed strings' used the chekker's tangent action, but its keyboard was placed alongside the string-band so that key-levers crossed the strings. (This layout would be imitated by the jack-action virginals.) Clavichords were low-cost, low-maintenance instruments and in fifty years they spread across Europe as the musician's work-horse for keyboard practice, study of scores, composing, voice training and choir practice. But the tangent action produced a sound somewhat soft in tone and cloudy in pitch. The clavicymbalum, 'keyed bells', retained by contrast the chekker's end-on keyboard while being mechanically far more complex in order to pluck or hammer the strings. It was invented in Vienna in the 1390s by physician-astrologer Herman Poll, and soon had numerous developers. Around 1440, perhaps at Dijon, another physician Arnault of Zwolle made engineering drawings of various mechanisms under the name clavisimbalum. Around 1460 in Pilzen, Paulirinus wrote that the clavicimbalum (sic) was 'sweeter and louder' than the clavichord. By this time its design focused on plucking rather than hammering. The name clavicembalum 'keyed dulcimer' implies hammering, but evolved into terms like clavicembalo and cembalo for the end-on plucker with jack action (the harpsichord). Costs of construction and maintenance were such that the clavicymbalum could never have existed without royal courts. At least seven documentary reports survive from before 1450, and a further fifteen along with a similar number of depictions from before c1500. Conrad Paumann (c1410-1473) The first major figure in two-hand keyboard repertoire is Conrad Paumann. Even after the death of J S Bach, a writer in Germany could hail Paumann as 'in all musical arts the most expert' (J. Staindl 1763, cited in The New Grove). Great was his fame. Born blind around 1410 in the imperial free city of Nuremberg, Paumann was sponsored by a patrician family to master the recorder, lute, harp, fiddle, portative and clavichord. He became organist at St Sebald's church, where a notable instrument was built in 1441 by Heinrich Traxdorff of Mainz with separate stops for Principal, Fourniture and Cymbale. It probably had mean-tone tuning. (Two and a half centuries later, the same post would be held by Johann Pachelbel.) By 1447 Paumann was known as the finest organist in Germany, and he had been appointed City Organist on the understanding that he would not leave Nuremberg without permission. But in 1450, after unsuccessful negotiations, he secretly fled to Munich several days to the south, to join the illustrious court of the music-lover Albrecht III, Archduke of Upper Bavaria. Paumann spent his remaining twenty-three years there, serving also dukes Sigismund and Albrecht IV in turn. The Wittelsbachs were the wealthiest of the three families from which the German emperor was elected, the others being the Habsburgs and Luxemburgs. Paumann's salary as court organist was seven times more than he had received in Nuremberg, and he was also given a house. The Duchess Anna soon negotiated Paumann's release from his obligations in Nuremberg. No organ in Munich may have compared with that of Nuremberg's Sebalduskirche, but Paumann's challenge henceforth was to provide music for court rather than church. In spite of his blindness, Paumann travelled widely. In May 1454 at the castle of Landshut, a hard day's ride to the north-east, he played several instruments for Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, erstwhile patron of keyboard-engineer Arnault of Zwolle. In 1466 he reported on a new organ at Nördlingen, two days north-west. In 1470 he even travelled with Albrecht IV across the Alps to Mantua, whose margrave Ludovico Gonzaga was Albrecht's brother-in-law. Paumann's playing caused such a sensation that he was called the cieco miracoloso 'miraculous blindman', given valuable presents and knighted. He turned down invitations to the courts of Milan and Naples. Such a triumph suggests that he chiefly played his own instrument. He was assisted by his son Paul. (Paumann had married in Nuremberg in 1446.) In 1471 he visited the Reichstag at Regensburg, two days to the north of Munich, where he played before Emperor Frederick III and all the princes of Germany. Paumann tuned the keyboard with pure thirds instead of pure fifths¬¬–a revolutionary practice which took root in his youth. This creative compromise permitted the keyboard to play chords and to render counterpoint, which led quickly to the major/minor tonal system and to 'harmony' as a third dimension in music. 'Mean-tone tuning', as it was later called, opened a door to a vast range of resolutions (appoggiaturas) and gravitational effects (modulations). The fundamental challenge facing Paumann was to play in three voices, and he developed a style described as 'the balancing of a highly ornamental distant, often using a standard virtuoso figuration, and a solid tenor-countertenor basis' (New Grove). The third voice might appear or disappear unexpectedly. (Addition of a third voice solely at cadences was already practised by the master of the Robertsbridge Fragment.) A court appointment would be of particular appeal to Paumann in providing a scribe to immortalise his work. Dictation was doubtlessly laborious, but was aided by Paumann's acclaimed powers of memory. He had already dictated, perhaps as gift to Albrecht III, the Fundamentum organisandi (on the CD Fundamentum) and he continued, as is here conjectured, with the Buxheimer Orgelbuch (though most pieces in the former have two voices and many in the latter have three). Thirty-five songs in Fundamentum organisandi or its companion the Lochamer Liederbuch are also found in 'Buxheim', either in straightforward manner (for singing or dancing) or set as keyboard fantasies with the melody hidden in the lower voices. (Alternative settings to Mit gantzem willen [Track 20] and Der Winter [Track 28] for example can be heard on the CD Fundamentum [Tracks 21 and 18]. The exquisite Redeutes in idem from Fundamentum organisandi (Fundamentum [Track 27]) reappears in 'Buxheim' where it is emulated by five similar pieces, all in different tonalities ('keys') [Track 35]. While Paumann's name can be detected only five times in the Buxheim manuscript, this is much more than any other. It was not yet customary to name the composer of every single written piece, and blindness surely affected Paumann's awareness of attribution. (He may even have been ignorant of insertions by others into his book as it grew into nine fascicles.) Thus the Buxheim music had one prime creator instead of being by 'Paumann and his school'. Paumann's surviving legacy, considered to be 'very limited' by the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1980), is radically enhanced when the bulk of the Buxheim Organ Book is attributed to him. The Buxheim Organ Book The Buxheimer Orgelbuch (henceforth 'BOB') is the most important repository of early keyboard music but fate rendered it difficult both to access and to understand. For centuries it was one of the sights of the famous Carthusian library at Buxheim (two days west of Munich), then in 1883 it was bought at auction appropriately for the Royal Bavarian State Library in Munich. In the 1950s it was recognised as a relic of court life in Munich itself, too secular and too sophisticated to have originated in the silence and austerity of a Charterhouse. Its first transcriber, Bertha Antonia Wallner, declared in 1958 that the name should be changed to Münchener Orgelbuch 'Munich Organbook', but her own publications continued the familiar usage. With today's knowledge, it would be more accurately called 'Munich Keyboard Book' Münchener Clavierbuch. BOB has 169 folios on which are written well over a thousand items. Included are preludes, songs (many for dancing or drinking), song-fantasies, settings of Gregorian chant, ornate intabulations of chansons, keyboard composition exercises (cadences and modulations), and basse danse compositions exhibiting a starry virtuosity which prefigures jazz pianism. (The present recording has examples of all categories except exercises and intabulations.) The manuscript's numbering, added late in the nineteenth century, totals 258 pieces, but the four separate fundamenta (keyboard grammars) contain a further 820 items which are unnumbered because they include sets of exercises. Yet these fundamentums also include short pieces called variously Redeuntes, Punctum, Cursus, Præambulum or Ascensus cum descensus. The manuscript begins with hymns addressed to Jesus and his mother Mary, followed by ten dance songs. (N° 4, for instance, is a three-voice setting of Wann ich betracht die vasenacht [Track 29b].) Only forty-nine pieces are sacred, and all these suit household devotions. The basic range is 2 1/2 octaves, c—f2 . In general BOB is neatly written but its inaccuracies reveal 'a degree of alienation from his work on the part of the scribe rather reminiscent of the garage mechanic who casually forgets to check one's brakes' (Bernard Thomas). Clearly he was not the composer. Nine different hands were identified by Eileen Southern (an African American), with one alone responsible for two-thirds of the collection (to N° 224) including the fundamentums 189 (specifically accredited to Paumann) and 190 (brief and banal—composed perhaps by the scribe himself for purpose of study). Later scribes simply added single pieces or small groups, except for the lengthy third and fourth fundamentums 231 and 236 which are both attributable to Paumann (the one by association with fundamentum organisandi and the other by accreditation). A typical misunderstanding is the judgement of the indefatigable B A Wallner that the said third fundamentum was written after Paumann's death by an unsung pupil who 'surpassed his master in many things'. Certain anonymous items are, like the second fundamentum, too crude to be by Paumann, such as an elementary basse danse called Jo götz (52) and two drab pieces written by W.K. (186, 187). Of special significance are seven anonymous pieces identifiable as English, by Dunstable, Morton, Bedyngham and Frye. Another three pieces close together seem to refer to two Munich courtiers (Antonius Baumgartner and Ulrich Fuetrer) and to a papal singer—110 Baumgartner [Track 39], 107 Der füterer [Track 40], and 113 Wilhelmus Legrant [Track 41]. Hitherto assumed to be composed by the said men, these pieces now seem to be portraits by Paumann. (Huizinga identified an interest in depicting personality as a characteristic of Renaissance art.) Paumann's two known pupils, interestingly, do not appear—his son Paul, who succeeded him as 'court organist', and Sebald Grave of Nördlingen. Alongside the birth of string-keyboard virtuosity, this music represents the commingling of German song and English-Burgundian compositional techniques. It may not have been heard as intended for some five hundred years. (Perhaps its last interpreter was Paul Paumann who died, an old man, in 1517. Furthermore, it was unsuitable for the jack instruments which were soon to replace the clavicymbalum and clavicytherium—the virginals and harpsichord.) In modern times, it has been simply assumed to be for organ yet it could best be played on the diminutive clavichord. The Wanner transcript Being the most important early keyboard manuscript, BOB was the first to be published in full. In 1955 the Bavarian musicologist Bertha Antonia Wanner (1876-1956) produced a photographic facsimile through the specialist house Bärenreiter, followed in 1959 by a punctilious three-volume transcript in modern notation. This presents each voice on its own staff, providing a visual equivalent to the tablature in which tenor and contratenor are depicted by rows of letters. The procedure, however, actually exaggerates the contrapuntal dimension, and the result is confining to read because the lowest voice is frequently on the middle staff. Moreover, it has the misleading appearance of organ music as usually notated today, on three staves. The chief uncertainty facing Wallner was the extent to which pedals were used. It is now apparent that this was very little. To play the music with fingers alone permits a quantum leap in tempo. Subsequent transcribers have placed both lower voices on an F-staff as usual for the left hand in keyboard music, and indicated the voice-leading by continuity-lines. A complete transcript is needed in this manner, with full index and concordance. By erring on the side of caution Wallner's transcript failed to make BOB readily accessible, but it provided an impeccable basis for future study. It generated significant investigations by Eileen Southern in 1963 (pointing to Paumann as the chief composer), Hans Zöbeley in 1964 and Christoph Wolff in 1968, and it contributed to Willi Apel's 1967 survey of early keyboard music. After this, research into BOB stalled. Redeuntes The six sections of the present recording begin with an abstract piece called redeuntes 'pedal point' (redeo, return). The repeated bass has the effect of a tolling bell. There are twenty such redeuntes in BOB, distributed among the three fundamentums by Paumann. All ten redeuntes in the present recording are found in the third fundamentum, apart from three in the first [Tracks 35, 36 and 37] and two in the fourth [Tracks 42 and 50]. In the twelfth century, Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis) wrote of Irish harpers who, besides playing 'the blunter sound of a thicker string, sportively play tinklings of the thinner ones'. The plaintive phrases in the redeuntes evoke Slavic or Bohemian song, and it might be relevant that the earliest known reference to the clavicytherium comes from Pilzen (c1460). The reduentes are basically of two voices but a third often makes a delayed entrance, imitating the treble at an octave below. In the performances here, the pedal-point is played an octave lower than notated, using the extra bass octave on the Ulmish clavicytherium. Such a transposition of the 'tenor' is often required in the redeuntes in order to accommodate the third voice, the 'contratenor'. (As interpreted here, the rhythm of the pedal point may be editorial but fifths and octaves are used only when indicated.) Kyrieleyson [Track 3a] The opening chant of the Mass Ordinary has four settings in BOB, this being the first. That it is item 150 may be significant. The opening Kyrie is Paumann's only extant four-voice piece. (The first significant masters of four voices on keyboard are Paul Hofhaimer and Arnolt Schlick, two generations later.) The tenor needs to be played an octave lower to form a consistent bass-line. This string-keyboard composition with its transparent texture may give an impression of Paumann's organ improvisation during the church liturgy, using a subbass pedal as was then available on large instruments. (In the very opening piece, Jhesu bone [Track 2], another hand has added a fourth voice as altus, but it is patently crude.) Salve regina [Tracks 5, 6, 7,8 and 9] This setting of the five verses of the popular hymn to the Blessed Virgin, the first of two, reveals a subtle integration of rhythm, melody and harmony. The lower voices are even less predictable than in the secular pieces, and the treble is spasmodically embellished with runs. Hofhaimer and Kotter would duly set the same popular hymn, as if in emulation of Paumann. The Salve Regina evokes Saint Mary as the ever-merciful source of comfort to the faithful, the fount of compassion for human frailty who cares nought for law and judges. Justice may be in the hands of the king's officials, but forgiveness is dispensed by the Church. Mary brings petitions to the feet of the Almighty ahead of all other saints. She is the one never-failing figure amidst the inequities of life, its injuries and senseless pain. Through faith and prayer, she heals the sick and suffering, frees the prisoner from his dungeon, and revives the starving with milk from her own breasts. Basses danses [Tracks 17, 23, 24,43,44,and 45] The basse danse was the principal court dance of the later Middle Ages. It may have originated in Languedoc, where as early as 1340 a troubadour sang of cansos e basses dansas. 'Basse' implied soft, courtly and dignified, in contrast to popular and less refined dancing to loud music. Basse danse is the earliest dance form for which the choreography has been preserved. The instructions stress grace and lightness of movement, with the body rising on the toes at every step in a swaying motion. The music was purely instrumental, based on a given tune (cantus firmus) played by the tenor instrument so slowly that one note lasted a whole bar. (In BOB it switches readily between the lowest and middle notes.) The basse danse provided instrumentalists with centre-stage gigs to show their skill. There are at least sixteen keyboard settings in BOB, of which eight use the same cantus firmus whether it be named Vil lieber Zeit or Annavasanna (a transliteration of Une fois avant que). Three of these are heard [Tracks 43, 44, and 45]. (In an earlier treatment of this tune, CD Fundamentum [Track 27] , it is called Anavois which by comparison with Annavasanna suggests that the scribe in Nuremberg was as devoid of French as his successor in Munich but was better at its simulation, if less inventive.) In the second setting here, which alternates between two and three voices, both hands have been transposed down an octave for sake of variety and because the deeper sonority suits the music's 'central core'. I am the bassadanza, queen of measures, and I deserve to wear the crown; few succeed in my employ and those who dance or play me well must perforce be gifted of heaven. —Domenico da Piacenza (c1450) English pieces [Tracks 31, 32 and 33] Johannes Tinctoris wrote in the 1470s that the music of his time was a 'new art', and that it originated among English composers the chief of whom was Dunstable. He added that the English had since been left behind by the French. Earlier in the century, English musicians would 'astonish everybody with their singing and playing at Cambrai'. Of the seven pieces by Englishmen in BOB, these three are the most likely to have originated as keyboard solos. They are the only surviving keyboard pieces from fifteenth-century England apart from a Gothic setting of Felix namque (heard on the CD Fundamentum [Track 11]). English musicians may have been the first to use mean-tone tuning. Dunstable's march Puisque mammon features busy upbeat ornaments comparable to the upbeat divisions still played by drums of the Royal Household cavalry. In the fifteenth century the English were widely feared, for their armies had thrice defeated larger ones of France—at Crécy in 1346, Poitiers in 1356 and Agincourt in 1415. It is conceivable that at the Battle of Poitiers the English leader, the Prince of Wales, had a chekker with him. Georg de Putenheim [Track 38] The virtuosic three-voice setting by Georg de Putenheim of the song Mein hertz in hohen freuden ist is the sole item of the present recording not in BOB. It was appended to a copy in Nuremberg of Fundamentum organisandi. Two settings of the same tune appear in BOB but neither is as flamboyant. The full title identifies the composer emphatically: Tenor Mein hertz in hohen freuden ist per me Georg de Putenheim. He appears to have been a student of Paumann who could match his master in virtuosity if not in harmony, poetry and architecture—as talented a pupil as Paumann could hope to attract. One imagines that he sent Paumann at Munich a copy of this, his finest composition since his master's sudden departure. Of course Paumann could not play it, and it was not copied into his great book. In return, possibly, Paumann sent copies of two of his unusual musical portraits which were appended to the Nuremberg manuscript [Tracks 39 and 41]. The ending of Putenheim's piece is not quite convincing, causing him to write a codicil as if for Paumann's benefit: et sic est finis. I Incomatus edis I In clepsedris edis 'and so it ends. Set forth in full leaf, in rhetoric full-blown'. The medieval clavicytherium The chekker was the first two-hand personal keyboard. The plucking clavicymbalum could be better heard in public, which helped keyboard music become both courtly and democratic. And it was conducive to tuning experiment which quickly led to mean-tone temperament. The first loud string-keyboard, however, to match the finger in speed, weight and sensitivity was the clavicytherium, 'keyed lyre' (kithara, lyre), a vertical clavicymbalum. Its plucking-clearance was virtually independent of the manner of the finger's striking the key. At the same time it was conceptually simpler, with only two moving elements while the clavicymbalum had three. (Common to both instruments was a spring-loaded tongue, which held the plectrum and allowed its return past the string.) The clavicytherium was superior in evenness, response and repetition. Indeed it was the most sensitive of all plucking instruments, offering better control than was later achieved with jack actions. It had other virtues, too. The projection of sound from the vertical soundboard was ideal. That levers jumped out when notes were played provided visual fascination. And since its height was maximised in relation to size, its appearance conveyed the spiritual power of a church spire. In the clavicytherium, a short balanced key-lever (190mm long in the present example) holds at its far (distal) end a vertical sticker (140mm long) to the top of which is affixed a right-angled extension (100mm) that comes forward just above the wrest-plank (which carries the tuning-pins and the nut), to reach through the string-choir and pluck with the spring-loaded plectrum. Thus the key-unit has a U-shape, side-on. The key itself sits, centrally-pinned, on a pivot-rail directly below the wrest-plank. Other restraints are a pair of guide-pins in the base-board for its distal end, and another pair in the top edge of the wrest-plank for the horizontal 'jack'-section which control the sideways play of the plectrum. These can readily be ajusted. There is prompt gravity-driven return with a weight of touch appropriate to the finger—indeed the leverage is sufficient for the pluck to resist the weight of the relaxed finger. And the compound key-unit has momentum enough to give a good sense of throw. (Removal of the key-unit, however, is laborious.) The clavicytherium was in use through the later fifteenth century, but there are only four documentary reports whereas the clavicymbalum has some fifteen—clearly it was uncommon. Its earliest sign may be Paumann's Fundamentum organisandi of c1450, but the first prescriptive evidence is the encyclopedia of Paulus Paulirinus of Prague, written c1460 in Pilzen, which gives the name innportile to a combined two-manual positive and clavicytherium (a claviorgan). Innportile est instrumentum mire suavitatis, habeas... 'The innportile is an instrument of wonderful sweetness, having a positive in one case and metal strings after the manner of a clavicimbalum standing upright in the shape of a half-psaltery in another. With one striking of the keys, each of these yields its sounds proportionately, blending with the others. It has the bellows of a positive and the attack of a clavicimbalum, complementing the sonorities of the positive with percussion' (translation by Standley Howell). Paulirinus, of Jewish extraction but kidnapped in infancy by Hussites, was baptised a Catholic at seventeen and ordained at Regensburg yet came to be identified as a Hussite spy. His encyclopedia was known at the Polish court. Only one copy survives, at Jagellon University Library, Cracow, Poland. It was said to have been hidden in the seventeenth century behind a royal memorial, whose secret was kept for a hundred years. A putative clavicytherium at the court of Savoy, described in 1485 as les petits argues dit exchaquiers 'the small organ called a chekker', was sufficiently sensational to be carried over the mountain pass from Chambery to Geneva and back. Further reports come from 1490 at Castile (a claviorgan owned by Crown Prince Juan), from 1497 in a sculpture in St Wolfgang's Church, Kefermarkt, Upper Austria, and a manuscript in Ghent University Library with eight schematic strings dating, as Christopher Page determined, from 1503-4. The third and best depiction of the medieval clavicytherium is a crude engraving in Virdung's Musica getutscht, Basle, 1511. This is the first use of the accepted name. A final sign of the instrument is simply its case on the keyboard wagon in the Triumph of Maximilian, 1512 (see the sequel CD Harmony-lore). One of 65 keyboard instruments in the estate of Henry VIII (1491-1547) was 'a pair of virginalles facioned like a harp', stored along with eight virginals and much furniture in the Long Gallery at Hampton Court. The young Henry, of whom Erasmus said 'there is no kind of music in which he is not more than moderately proficient', may have learnt on this instrument. A similar inventory from the royal palace in Madrid in 1602 includes 'a small triangular clavicordio in the style of a claviorgan', in ebony with gold strings. These instruments disappeared long ago. The Ulmish clavicytherium At least two medieval clavicytheriums survive. The smaller, at Yale, is a pillared cabinet with keys permanently on view and no sign of the triangular shape of the string band. (In this it like the chekker.) Its compass is basic to the Buxheim music, c/e—f2, 26 notes. (The outer range is given in the Tabula manucordij on folio 168r of BOB, but c# is never used in the music and the next three inflections are rare. Occasional downward extensions as in Nos 5, 78 and 162 possibly relate to non-keyboard instruments.) The larger clavicytherium was made in the imperial town of Ulm in 1470, as is revealed by a document used as parchment in its construction. It survived long in Venice, eventually to be exhibited by its owner Count Correr in 1894 in London where it was purchased by Sir George Donaldson for the Royal College of Music. Similar clavicytheriums with open belly and narrow soundboard exist in Stockholm (1657) and Oslo (also of the seventeenth century). By comparison, the oldest extant harpsichord is dated 1516 (made in Lucca for Pope Leo X and now in Siena), virginals 1523 (Verona/Paris) and clavichord 1543 (Naples/Leipzig). The Ulmish clavicytherium matches BOB in not only date and provenance but also compass. Admittedly it has forty notes but these include two in the treble which bring it to a common sixteenth-century limit g2 and twelve in the bass which extend it an octave to C, mentioned as a keyboard limit in Bolognese treatises of 1431 and 1482 and used, for instance, in 1464 in an organ in Cremona. (In the next century, the peerless collector Henry VIII would call keyboards to c or F 'single' and to C 'double', and this 'bass C' would even be attained with gut strings by the 1530s on the viol, cello and double bass.) The Ulmish clavicytherium has eight keys below c, indicating a short octave. C is sounded in conventional manner by the E-key at the start of the keyboard, D by F# and E by G#. (The short-octave is a feature of most early keyboards including the Yale clavicytherium and all seven extant sixteenth-century clavichords.) The Ulmish keyboard initially had a short key between the first two long keys, instead of a key for F#. Absence of this most likely of bass inflections confirms that the bottom octave was indeed diatonic. The octave extension of the bass is essential for many of the BOB redeuntes and the Kyrieleyson [Track 3] and Anna vasanna [Track 45]. The Ulm instrument is made of six different timbers. Its sumptuous decorative scheme included a carved tableau, now missing all detail. In the opinion of David Evans who made the copy used in the present recordings, the filigree of the sound-hole traceries, as far as extant, could not be re-created without years of preparatory training. The 1991 copy involved conjecture about such vital parameters as string-material, plectra, dampers and touch. Only recently had it been appreciated that Virdung's book of 1511 referred to gut strings not on the clavicytherium in general but on a specific virginals (Stradner 1983). Being so much a mystery the instrument was ignored by pioneering harpsichord historians Raymond Russell and Frank Hubbard, yet it exhibits craftsmanship of a rare order and has the compass of a cutting-edge commission. Is it the very instrument that Paumann took across the Alps from Munich to Mantua in the company of his son Paul and Duke Albrecht IV in 1470?