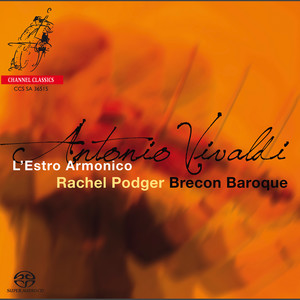

Vivaldi: L'Estro Armonico

- 演奏: Rachel Podger (拉切尔·波杰) (小提琴)/ Rachel Podger (拉切尔·波杰) (小提琴)

- 发行时间:2015-03-10

- 唱片公司:Channel Classics Records

- 唱片编号:CCSSA36515

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

Disc 1

-

作曲家:Antonio Vivaldi( 安东尼奥·卢奇奥·维瓦尔第)

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 3, RV 549( D大调第一号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 549)

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 2 in G minor , Op. 3, RV 578( G小调第二号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 578)

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major, Op. 3, RV 310( G大调第三号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 310)

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 4 in E minor, Op. 3, RV 550( e小调第四号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 550)

-

1001:45

-

1102:15

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 5 in A major, Op. 3, RV 519( A大调第五号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 519)

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 6 in A minor, Op. 3, RV 356( a小调第六号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 356)

Disc 2

-

作曲家:Antonio Vivaldi( 安东尼奥·卢奇奥·维瓦尔第)

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 7 in F major, Op. 3, RV 567( F大调第七号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 567)

-

19Brecon Baroque / Rachel Podger / Bojan Cicic / Johannes Pramsohler / Sabine Stoffer / Alison McGillivray02:24

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 8 in A minor, Op. 3, RV 522( a小调第八号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 522)

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 9 in D major, Op. 3, RV 230( D大调第九号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 230)

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 10 in B minor, Op. 3, RV 580( b小调第十号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 580)

-

28Brecon Baroque / Rachel Podger / Bojan Cicic / Johannes Pramsohler / Sabine Stoffer / Alison McGillivray03:26

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 11 in D minor, Op. 3, RV 565( d小调第十一号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 565)

-

作品集:Violin Concerto No. 12 in E major, Op. 3, RV 265( E大调第十二号小提琴协奏曲,Op. 3, RV 265)

简介

Brecon Baroque Rachel Podger violin/director Bojan Čičić violin (solo nos. 2 & 11) Johannes Pramsohler violin (solo nos. 5 & 8) Sabine Stoffer violin Janes Rogers viola Ricardo Cuende Isuskiza viola Alison McGillivray violoncello Jan Spencer violone Daniele Caminiti theorbo David Miller theorbo/guitar Marcin Świątkiewicz harpsichord/organ Keyboards provided and tuned by Malcolm Greenhalgh Vivaldi has, above all, always struck me as wonderfully entertaining. His musical shapes and figurations seem to exist in order to please and surprise. Always supremely idiomatic (although sometimes idiosyncratically specific), there’s also that sense of directing a sensation with a particular person in mind. In the twelve concertos which comprise ‘L’Estro Armonico’, these qualities abound, not least because Vivaldi appears to have taken extraordinary trouble to exhibit his craft to the world, almost as a way of ‘setting out a stall’ for how a new 18th-century concerto could now be written in the right hands. Underpinning Vivaldi’s flair, originality and meticulous attention to detail is an engine room of momentum: raw energy is regularly the order of the day with muscular layers of semiquavers and rapid acrobatics passed between the various configurations of soloists. These pieces are truly exhilarating to play and perform and their fresh impact never fails to hit some target or other, judging by the reaction of a live audience. Not often do you witness four violins trying to outdo each other! During Brecon Baroque’s concerts preceding the recording, the rapier-like turns in musical conversations between the four parts always seemed to lead to added expectation and excitement – all the more effective because of the contrasted moments of deep melancholy which Vivaldi somehow manages to express irrespective of mode; like Schubert, a major key can be just as poignant and affecting as a minor in a conceit of sadness or loss. For example, in the slow movements of concertos no. 9 and no. 12 in D and E major respectively, there is an exquisite tenderness in his writing, something fragile, innocent and temporary; I catch myself wondering for whom these moments were created… I would like to thank all my wonderful colleagues for these many intense moments of energy, tenderness and joy while performing and recording these fantastic concertos – works which intrigued Bach and from which he mined so many of the very finest Vivaldian attributes. Rachel Podger ♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢♦♢ Vivaldi L’Estro Armonico Antonio Vivaldi’s reputation as a composer of instrumental music was well established in his native Venice by the end of the eighteenth-century’s first decade, due in large part to exemplary performances given by his pupils at the Ospedale della Pietà. There is evidence from manuscript copies of his concertos that his fame was beginning to spread beyond Italy from about 1700. But we can pinpoint the composer’s pan-European celebrity precisely to 1711, the year in which the Amsterdam publisher Estienne Roger published twelve of his concertos as Opus 3 with the title L’estro armonico. No other publication had such an electric and immediate effect on the eighteenthcentury musical world, and few left a deeper impression on the musical practices of the era. Soon after Roger’s publication, the concertos also appeared in editions in London (John Walsh) and Paris (Le Clerce the younger). J. J. Quantz heard some of the concertos near Dresden in 1714, and later recalled that ‘as pieces of a type that was then completely new, they made no small impression on me’. J. S. Bach arranged no fewer than six of the concertos for organ or keyboard instruments and strings. The title of the collection encapsulates the qualities that so entranced Vivaldi’s contemporaries. L’estro armonico, which might be translated as ‘musical rapture’, reflects the vitality and freshness of Vivaldi’s invention: its rhythmic energy, melodic and harmonic intensity, textural sensuousness, performative brilliance and dramatic flair. For composers, these concertos offered a startlingly original blueprint in how to shape musical time through the articulation of a new functional- tonal style of contrasting keys and cadences, and – more profoundly still – how to develop musical ideas rationally and coherently into large-scale forms through the system of ‘ritornelli’ or ‘little returns’. The way in which these pieces are conventionally described as concertos for one, two or four violins rather simplifies a more complex truth about them. Roger issued the concertos in a set of eight partbooks: four violin, two viola, one cello, and one ‘continuo e basso’. This provided a framework for a broad spectrum of textural, colouristic and stylistic effects: whether the pitting of a solo violin against the rest of the ensemble after the model of Torelli, or a Roman-style concertino of two solo violins and cello against the other five parts in the manner of Corelli, or the more kaleidoscopic possibilities of four independent violin lines, divided violas, and differentiated cello and continuo parts. That said, a broad generic pattern is perceptible across the set as a whole, with four groups of three concertos. Each group begins with a concerto in which all the instruments can take on solo roles, followed by a concerto in which the concertino of two violins and cello predominates, and finally with a concerto where the first violin is definitely primus inter pares. With so much intoxicating variety on display, a key aspect of Vivaldi’s achievement in L’estro armonico was to bind all the disparate elements together with the force of his musical personality. Take, for example, the first movement of the D major concerto which begins the set. The number of ideas contained in its 85 bars is astonishing enough – from the opening declamatory fanfare on a solo violin, through motives ricocheting between the four violins, through passages where the cello is the leading voice, to the ‘wall of sound’ effects of eight separate euphonious string parts in concert. But the real joy of the movement is Vivaldi’s ability to place such contrasting materials side by side with such conviction that they cohere into an improbable but exhilarating entity. Similarly, the concertos in E minor (no. 4), F major (no. 7) and B minor (no. 10) include movements that build up complex interactive patterns between the four violins, sometimes in dialogue, sometimes – for example, in the B minor concerto’s remarkable Larghetto movement – by overlaying different melodic figures to produce shimmering textures. Yet in these same concertos Vivaldi is also content to devote passages to first violin solos and to textures which pair the violins in duo configurations, without in the least compromising the integrity each concerto’s individual identity. The concertos with the concertino group of two solo violins and cello highlight different types of collaboration and competition: from the shifting allegiances between the first and second violins and cello in the G minor Concerto (no. 2), the duel between the two violins in the first movement of the A major Concerto (no. 5), the contrasts between sonata-like ensemble writing and soloistic jostling of the D minor Concerto (no. 11), to the elaborate dialogues of the A minor concerto (no. 8) which anticipate Bach’s great Double Concerto. The first violin predominates in the remaining four concertos (no. 3 in G, no. 6 in A minor, no. 9 in D major, and no. 12 in E major). There is a strong emphasis on technical brilliance in their outer movements, while their central movements bring to the fore the affective qualities of the violin, whether in sonata-like writing (in nos 3 and 9) or in arias (nos 6 and 12) which open a window on Vivaldi’s operatic genius. Timothy Jones