- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:André Caplet

-

作曲家:Luctor Ponse

-

作品集:Trois Chants

-

作曲家:Rosy Wertheim

-

作品集:Trois Chansons

-

作曲家:Matthijs Vermeulen

-

作曲家:Jacques Ibert

-

作品集:Deux Stèles Orientées

-

作曲家:Henriëtte Bosmans

-

作品集:Terugblik

-

作曲家:Francis Poulenc

-

作品集:Tel Jour Tel Nuit

简介

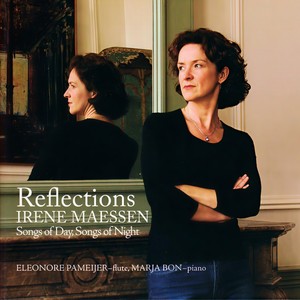

The French influence on Dutch musical life between the two world wars began increasing as never before. Modern French repertoire was becoming a common part of every program, even with the Concertgebouw Orchestra thanks to the efforts of conductors such as Pierre Monteux and Eduard van Beinum. The climax was perhaps the French Music Festival in 1922 in Amsterdam, where Darius Milhaud and Maurice Ravel were present. France also attracted Dutch musicians during this period. Not only was Paris a magnet for artists from all over the world, the younger generation of Dutch composers wanted to end the hegemony of the German Romantic tradition in Holland. This new orientation was partially responsible for why composers such as Matthijs Vermeulen and Rosy Wertheim left for Paris. In Holland, the influential composer and teacher Willem Pijper helped spread the French style to his students Piet Ketting, Rudolf Escher and Henriëtte Bosmans. This CD of songs for soprano and piano is a reflection of this period. Next to the well-known Francis Poulenc are such lesser-known French composers as Jaques Ibert and André Caplet. These last two composers, just like Rosy Wertheim, added the typically French instrument, the flute, to their songs. The Dutch contribution to this CD is partially in French (Vermeulen, Wertheim) and partially in Dutch (Bosmans). Literally on the border of these two cultures is the Dutch-French composer Luctor Ponse, whose diverse oeuvre is only now just being rediscovered. Besides being a conductor, composer and a close associate to Claude Debussy, André Caplet was also a vocal accompanist. That Caplet has left us forty mélodies (mélody being the French pendant of the German lied) shows his affinity to vocal music. His first endeavor in this genre was Viens! Une flûte invisible soupire from 1900. The 22 year-old clearly refers to Saint-Saens setting of the same poem by Victor Hugo for flute and piano accompaniment. From the very first measure, Caplet’s flowing music has a Debussy-like atmosphere. The flute plays a prominent role, initially as a shepherds instrument, than later representing birdsong. Luctor Ponse was born in Genève, the son of a Dutch father and a French mother. He studied piano in the city of his birth as well as in Valenciennes, France, won a composition competition in Brussels, and settled finally in the Netherlands. He quickly achieved fame as a pianist creating a furore with Bartók’s piano music. As a composer, he wrote in a clear and lyrical style, later writing both twelve-tone and electronic music. In 1940-41, Ponse wrote Trois Chants, a vocal triptych using French poems. In Appareillage, the ubiquitous sea can be heard in the piano’s murmuring motive and later two repeated bass notes as the sailors hoist the sails; in the voice, the tension of the approaching farewell can be felt. Reflets is a calm and introvert song about man and nature. The repeated chords in the piano create an onerous mood, unbroken until the final expressive strophe. Guêpe closes the triptych relaxed and playful. The active piano accompaniment, the warm-blooded melody line of the voice and a few jests (such as the short pause after the words “s’arrête un peu”) lead to the radiant conclusion. Just as Bosmans, Ponse and Poulenc were, Rosy Wertheim was also originally a pianist. In 1929, she quit her teaching position at the Amsterdam Music Lyceum in order to concentrate fully on composing. She travelled to Paris for study, keeping in touch with Honegger, Ibert and Jolivet. Her planned stay of six months turned into six years, after which Wertheim returned to Amsterdam via Vienna and New York. For the Trois Chansons, Wertheim used texts by the 8th-century Chinese poet Li Tai Po, who had inspired her 12 years earlier to compose La Chanson déchirante. Li Tai Po had a lust for life, travelling extensively and turning his impressions into imaginative poems.Wertheim’s music for Trois Chansons are just as sensual as the texts. The flute plays an important role, imitating human laughter in La Danse des Dieux and is responsible for attractive intermezzo in Les deux Flûtes. The piano stays primarily in the background, except in the cheerful final song, Sur les Bords du Jo-Jeh, in which horsemen are depicted. Besides inflation and shortages of provisions, neutral Holland had few problems during the First World War . Despite this, in 1917, the 29 year-old Matthijs Vermeulen wrote 4 war songs, one of which was Les Filles du roi d’Espagne. He followed in the footsteps of his mentor, Alphons Diepenbrock, one of the few civilians really concerned about the atrocities occurring across the border. The text of Les Filles du roi d’Espagne is based upon a fairy tale-like folk song, arranged by the poet Paul Fort. Three princesses reflect upon their beloveds, who find themselves on the battlefield. The message is that love and war do not mix. The compassion for the victims and the childlike atmosphere go hand in hand with the choir piece Trois beaux oiseaux du paradis that Ravel composed two years earlier. Vermeulen emphasizes the timeless character of the story in his musical setting. He keeps to the traditional alternation of verse and refrain, adding archaic harmonies to the piano accompaniment. The composer was apparently satisfied with the result: in a letter dated 1946 to his second wife, Thea (Diepenbrock’s daughter), he praised the “naive, primitive, soft but nonetheless very deep lyricism” of this song. It was in that year that he returned for good to the Netherlands, after a quarter of a century of self-imposed exile in France. Rome was where Jacques Ibert spent most of his professional career. Being awarded the Prix de Rome directly after his conservatory studies took him to the Italian capital, where he stayed for two years. He later returned there as director of the Académie de France. Ibert is mostly known for his chamber music for winds—he had a fondness for the flute—though he wrote almost thirty mélodies. In his diptych Deux Stèles orientées from 1925 for soprano and flute, Ibert focuses on ancient China. He used two prose poems by Victor Segalen, a former marine doctor who settled in China in 1910. Segalen’s volume of poetry Stèles refers to the numerous commemorative stones that can be found in China along roads and in cemeteries. The inscriptions on these stones that face east (“stèles orientées”) are traditionally about love. Yearning is the theme in Mon amante a les vertus de l’eau, which begins almost as an improvisation and gets lighter as it goes. On me dit is distinctly theatrical: the flute gives ironic comments during the speech given by the soon-to-be-married groom. At the end of the Second World War, Henriëtte Bosmans broke a long, compositional silence that had begun ten years earlier with the death of her fiancé, the violinist Francis Koene. Her revival as a composer resulted in almost entirely vocal music. Between 1945 and 1951, she composed more than thirty songs to Dutch, German and primarily French texts. Most of these songs were for the French singer Noëmie Perugia, with whom Bosmans formed a duo towards the end of her life. The cycle Terugblik (“Reflection”) was commissioned in August 1947 by the Dutch government. Her mother collected several volumes of poetry for her, from which Henriëtte Bosmans chose two poems by J.W.F. Werumeus Buning and two by Adriaan Roland Holst. These four poems do not tell a rounded story, but share a reflective and melancholy character. Drie brieven (“Three Letters”) tells of three letters that the deceased has sent to his beloved, In den Regen (“In the Rain”) contemplates the incessant rain, Dit eiland (“This Island”) ponders on why we were put on this earth and Teeken den hemel (“Draw Heaven”) dreams about all of the things that has taken place and of all of the people that have come and gone. Terugblik comes across like one, long ballad: the austerity of the music joins these four songs together. Bosmans chooses a sober piano accompaniment and a recitative-like discourse, especially in Dit eiland and Teeken den hemel , in which entire lines are declaimed on one single note. Although reflections on life and death predominate, the cycle has moments of lyricism and graceful episodes. Francis Poulenc was eighteen years old when he heard the three-year older poet Paul Eluard read from his own works in a Paris book store. He was impressed by Eluard’s warm voice, which he later described as “alternatively soft and violent, muted and metallic”. Such contrasts can also be found in the 9 movements of the song cycle Tel jour, telle nuit. This serious piece arose in the quiet winter months of December 1936 and January 1937, intended for the baritone Pierre Bernac with whom Poulenc had formed a duo less than two years prior. With the exception of the final poem, all of the texts come from Eluard’s volume Les Yeux fertiles. Poulenc arranged the cycle himself and asked Eluard for a new title. Eluard came up with Tel jour, telle nuit, a reference to the time span between the first and last poem. The peaceful atmosphere of dawn prevails over the first song, Bonne journée, dedicated to Picasso. The concluding, intimate Nous avons fait la nuit is a modest ode to nocturnal love. The melodic and rhythmic relationship between the two songs gives the cycle its internal cohesion. Along the way, we come across all sorts of moods which Poulenc succinctly portrays: from unbelievable solitude to a devilish gallop, from a solemn hymn to screaming and disillusionment. The cycle ends with a cantabile postlude in the piano. According to Poulenc, this extended coda is anything but gratuitous. It is to enable the listener to hold on to the emotions just a little bit longer, just as in Schumann’s Dichterliebe.

![BORDEWIJK-ROEPMAN, J.: Vocal and Chamber Music (From the Bottom of My Heart) [Maessen, Schoch, Scholten, Worms]](http://y.gtimg.cn/music/photo_new/T002R90x90M000001SPWHY0yl355.jpg?max_age=2592000)

![MOMPOU, F.: Combat del Somni / Suite compostelana / El niño mudo / Comptines (El Pont) [Maessen, Kooten, Esser, Kaaij, Worms]](http://y.gtimg.cn/music/photo_new/T002R90x90M000001Hwkrv3dEESg.jpg?max_age=2592000)