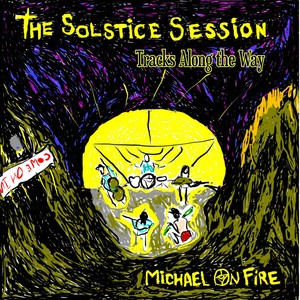

The Solstice Session / Tracks Along the Way

- 流派:Rock 摇滚

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2017-04-05

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

Disc1

Disc2

简介

In the 1990s, at a time when there was a definite distinction between “local acts,” “regional acts,” and “national acts,” Michael On Fire occupied a unique place in American music culture when he became “a local act all over the Country.” Playing a circuit of gigs that spanned the entire geography of the United States, he traveled to towns hundreds and thousands of miles apart three and four times a year, where he became familiar, with and to, “the locals” in a way that removed the usual separation between “the person on the stage” and the people in the audience. Articles and interviews appeared regularly in the “local papers;” the local radio stations played his music, and he appeared on local TV shows. Other local bands and musicians played his songs at their gigs, just like they might do with more well-known national acts, only he and they played in the same venues. The scope and the sphere of his influence was national, but the perception and the relationships were more akin to a local band. By this point in his career, he had already been writing and recording and gigging for over 20 years, all original music. Signed early on as an artist and songwriter to Groovesville Music, he cut his teeth working out of the famed United Sound Studios in Detroit with the great Don Davis, and through him with a stable of artists that included The Dells, the Dramatics and Johnnie Taylor; in the still-early days of Country Rock, he recorded at Muscle Shoals Sound in Alabama with The Swampers, playing his songs; Stephen Stills and Joe Vitale produced him in Los Angeles, where artists he respected came to his gigs to hear him play. And he played all the time, all over the place, in blues clubs and jazz clubs, and dive bars, and concert venues and festivals, as a headliner and as support for many of the top names in rock, blues, jazz, and roots music. He was, and had long been, a full-time musical artist, with thousands of gigs under his belt. He lived in Detroit, and Los Angeles, and Nashville, but mostly out of a van and motel rooms. This was before the digital age; before social media and YouTube, before every band and musician had their own website, and before cell phone use by the general public. The world was moving into a new millennium with technology leading the way, but Michael was determinedly old school. While others were keeping in touch electronically, he was still pulling up to phone booths with a bag of quarters. As the 20th Century drew to a close, his band mates and traveling companions “ran out of gas” and called it quits. Suddenly solo, Michael paused to envision the next phase of his life and journey as a musical artist. Perhaps in an attempt to have a more normal family life, he came off the road and out of the clubs for the first time in a dozen years. He made a solo album, one voice – one instrument, in Nashville. He wrote and recorded instrumental music that became among the most played music on The Weather Channel, and would remain so for many years. But it wasn’t enough – to keep his marriage and family from breaking apart, which left him with a broken heart; and that became a predominant feature moving forward. When he came through on the other side of the personal and cultural changes, he found himself standing in a world that looked and felt and, in fact was, very different. In almost all of the towns, the venues he played had closed down, and the people who owned and booked and frequented them weren’t around anymore. The local newspapers and the writers who worked at them were disappearing at an alarming rate, and the local radio stations all got bought up by the media behemoth that stole the airwaves, fired the DJs and switched the formats to automated programming. Consolidation, homogenization and compartmentalization were the order of the day, and that which was “out of the box” was out of the loop. A new network of venues and promoters and broadcasters, and alliances and guilds and organizations arose, which operated according to a different paradigm. More than ever, image overshadowed essence and form eclipsed content. As often happens during times of transition and relocation, some things can get lost or misplaced in the process, and in this case it was “the file” on Michael On Fire; the record of his feats and adventures and accomplishments. His data was not recognized by the new operating system, and what moderate assets he had managed to accrue were deemed to be no longer of value. While this is not a typical tale, neither is it entirely unfamiliar; cultural and technological changes often yield casualties of transition. That’s why the oral record is scattered with reports of lost legends and hidden treasures, and why when we discover them in our midst it is important to identify them in the lineage and if possible acknowledge, support and sustain them. Many have asked, and I often wonder, how it could’ve happened that the dots didn’t get connected; how each of the towns remained discrete and isolated from each other. The answer lies in the unique phenomenon of being “local all over the Country.” Local media doesn’t affect or connect with other local media; it takes national media to do that. For an independent artist whose grass roots travel places him below the radar and the awareness of national attention, the way to get national media is to pay for it, and as Michael reveals here in his song “No One to Kill,” – “I’m not one of those who pay …” (and some would add, nor is he one to sell, as in “sell out.”) Michael On Fire is no longer “a local act all over the Country;” now, he’s more like one of our mythic winds, like the Santa Ana, also sung about here, in that he blows in every now and then, shakes things up, and then moves on out. He has never stopped writing, recording, gigging or touring, and as his longtime fans will attest, he continues to get better and better.