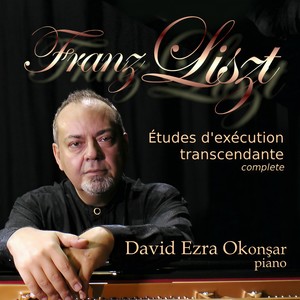

Franz Liszt: The Transcendental Etudes

- 歌唱: David Ezra Okonsar

- 作曲: Franz Liszt (弗朗茨·李斯特)

- 发行时间:2015-05-20

- 唱片公司:Lmo-Records

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:Franz Liszt( 弗朗茨·李斯特)

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 1 in C Major, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 2 in A Minor, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 3 in F Major, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 4 in D Minor, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 5 in B-Flat Major, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 6 in G Minor, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 7 in E-Flat Major, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 8 in C Minor, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 9 in A-Flat Major, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 10 in F Minor, S. 139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 11 in D-Flat Major, S.139

-

作品集:Transcendental Etude No. 12 in B-Flat Minor, S. 139

简介

The Etudes d'Execution Transcendente are fully original compositions, not transcriptions or arrangements. The series which makes the foundation for all piano music which has been composed afterwards, gets its final aspect in 1851. As early as 1826, when he was fifteen, Liszt started "Etudes pour le piano-forte en 48 exercices dans tous les tons majeurs et mineurs". They are actually didactic exercises in the spirit of a Cramer or Czerny. Twelve of them were finished and published. In 1837 Liszt was in quest of expanding the piano technique to new territories and started to rework on this early attempt. He kept the initial thematic material and rewrote them including amazing and incredible new technical "tour de forces". However it would be erroneous to see in this series of Etudes just a showcase for pianistic virtuosity display. The composer was then immersed into romantic poetry and literature. Many of the Etudes then got a suggestive title which refers to a piece of literature. As such, these Etudes are, according to Claude Rostand, "the first state of an embryo which will evolve into the core of the programme-music." The Creation Of The Modern Piano Music Language F. Liszt The Transcendental Études (S.139) complete recording by D.E. Okonsar The technique of playing the keyboard instruments can be roughly summarized as starting with the use of fingers only, i.e. the early Virginal, harpsichord music, going towards the use of the entire upper body for grasping a larger range of a wider keyboard and a bigger sound volume with the appearance of the modern piano. This evolution which can be seen clearly in the works of Orlando Gibbons; William Byrd; followed by J.S. Bach, specially the Goldberg Variations are a turning point in keyboard playing technique, then the composer sons of Johann Sebastian Bach, specially Johann Christian and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach radically changed not only the musical style but also, inevitably, the keyboard technique. Those techniques which include wide-range running scales and arpeggios, alternating and double thirds and sixths, newly put in use by the composer sons of J.S. Bach were then emancipated mainly by Joseph Haydn and by W. A. Mozart. Beethoven took them from there and drove up. Starting from his sonatas opus 2, opus 7 and opus 10 these techniques attained their limits. With his later sonatas, Beethoven emancipated on them. Here intervenes Carl Czerny (1791 - 1857) who actually made a series of "catalogs" of that technique for use in piano learning, that is his "famous" Etudes. Franz Liszt, learning from Czerny (himself) worked creatively and arduously on his own piano technique and conceived a further higher level of playing. His use of the arms and upper body are best described in a few caricatures which were published in newspapers of his time. With the advent of the first "modern" pianoforte, released in 1851 by Bösendorfer which has a huge body, thick and long crossed strings, specially in the lower bass region, the instrument as we know today was here. The playing technique, the sound volume needed by larger halls and audiences and the musical language associated with it was there also. Since then neither the technique or the instrument changed radically. Ravel, Scriabin, Prokofieff, but also Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky all elaborated on techniques revealed by Franz Liszt. A radical step forward not only with its predecessors (Beethoven, Czerny) but also with its contemporaries (Chopin, Mendelssohn) Where Liszt's contemporaries, like Felix Mendelssohn were mainly concerned about "using" the new instrument and its playing techniques to express their musical ideas, Liszt attempted to have the new playing possibilities make for new musical ideas. That is where the "modernity" of Franz Liszt resides. A new language, complete with its new vocabulary and grammar was possible with this "new" instrument with its deep basses, long resounding pedal and huge volume and dynamic range. This is also the main point where all the production but specially the Etudes by Liszt differ from that of Chopin. Even when not referred to directly, most or all of Liszt's Etudes draw their inspiration from literary sources. The pianistic "subject matter" (technical things like octaves, scales etc.) is not the "subject" of the Etude. The Etude is a free-form piece which makes use of the widest possible pianistic possibilities imagined, made possible or expanded by Liszt. The above point is the main difference with the Etudes by Chopin. In Chopin the pianist "subject" makes the central theme of the Etude which then develops it into a full piece. In Liszt the piece is imagined independently from the pianist "subject" or "subjects" and the pianistic possibilities required to render the musical idea to its fullest are drew, if needed expanded, developed or even created, from the pianistic virtuosity the composer crafted since his early years. The modernity in Liszt's music comes from disdain of the traditional musical forms. Even when he adopts one like the "Sonata" (in B minor) or "Symphony" ("Faust" and "Dante") he turns them into "free" symphonic or pianistic poems. In this sense he is more close to Schumann than to Chopin for instance. The musical form's freedom is then easily reflected over the harmonic language which in turn easily frees himself from the tonal framework. Franz Liszt created the modern piano technique. As Saint-Saens put it: "On the contrary of Beethoven who did not care of the limitations and the morphology of the pianist's hands and imposed upon them his musical ideas, Liszt trained and emancipated the pianist's technique and abilities so as to obtain without constrains the maximum results." Without being a "revolutionary" composer, Liszt did make the piano sound as one totally new, previously unheard instrument. Changes in the piano building, mostly initiated by Bösendorfer, resulted in an instrument as we are familiar with today: coiled bass strings, huge body. This instrument appeared around 1850's, some ten years after the death of Chopin thus unknown to the Polish composer. Liszt was the one who has used its possibilities: deep and long resounding basses and huge sound output with his typical double octaves, tremolos in both extreme-high and extreme-low registers. Virtuosity is one keyword most often associated with Liszt. But as Alfred Brendel said it, if Liszt sounds "flashy" and "vulgar" it is because it is played that way! Actually for Liszt, virtuosity is always a means to another end. This end is to transcend the possibilities of the instrument or of the music (of his time) by means of a precise, powerful and many has put it this way: a diabolic technique. The Etudes d'Execution Transcendente are fully original compositions, not transcriptions or arrangements. The series which makes the foundation for all piano music which has been composed afterwards, gets its final aspect in 1851. As early as 1826, when he was fifteen, Liszt started "Etudes pour le piano-forte en 48 exercices dans tous les tons majeurs et mineurs". They are actually didactic exercises in the spirit of a Cramer or Czerny. Twelve of them were finished and published. In 1837 Liszt was in quest of expanding the piano technique to new territories and started to rework on this early attempt. He kept the initial thematic material and rewrote them including amazing and incredible new technical "tour de forces". However it would be erroneous to see in this series of Etudes just a showcase for pianistic virtuosity display. The composer was then immersed into romantic poetry and literature. Many of the Etudes then got a suggestive title which refers to a piece of literature. As such, these Etudes are, according to Claude Rostand, "the first state of an embryo which will evolve into the core of the programme-music." The tonal succession of the Etudes are remarkable too. They move as tonic, relative, sub-dominant. That makes a descending scale by thirds: C - A - F - D - B-flat ... a feature which is going to be seen in many of Wagner's harmonic progressions. Even though mostly heroic in character, The Transcendental Etudes (S.139) cover the entire spectrum of feeling translated for the piano. They can be extremely delicate, tender, impressionist as well. Etude No. 1 (Preludio) in C major Despite the appearances, the Etude No. 1 in C major: "Preludio", is not just a "warm-up" exercise, but a powerful and evocative introduction to the series. It swiftly expands to the entire spectrum of the keyboard and raises the curtain for the dramatic pieces to follow. To be noted in this short number is the plagal cadence which undoubtedly adds to the grandeur of this prelude. Etude No. 2 (untitled – Molto vivace) in A minor The Etude No. 2 in A minor, (untitled: "Molto vivace") is a bravoura piece full of vehemence and expressionism. It is somewhat close to Paganini etudes in a few aspects of its ecriture but certainly not in content. The "diabolical" minor second interval used with insistence makes its particular style. Etude No. 3 (Paysage) in F major A serene pastoral scenery with a beautifully simple charm characterizes the Etude No. 3 in F major: "Paysage". The piece oscillates between an evanescent imagery and dense, oppressive feelings. The intricate "orchestral" writing proves that even the young Liszt was able to "think orchestra" when composing for the piano. Etude No. 4 (Mazeppa) in D minor From the magnificent large scale Etude No. 4 in D minor: "Mazeppa", dedicated to Victor Hugo, Liszt will later extract the substance for his Symphonic Poem with the same title. A large scale "tragedia" one of the most revealing compositions for the piano of the Hungarian composer. The trepidations of the hero, riding tied up on the back of a horse in the steppes of Ukraine is revealed after a short introduction. The dramatic main theme is presented with block chords in both hands with alternating thirds, also in both hands, at the middle section of the keyboard. This theme, of the riding of the hero, will be exposed four times with its rhythm getting more and more squeezed: periods of eight, six, three and two units. After one lighter section in B-flat major the "story" reaches its climax and the hero falls at last. A recitative marked: "il canto vibrato ed appassionato assai" with evocative calls of the name "Mazeppa" over diminished seventh intervals ("D - C-flat-up - D" as "ma - zep - pa") seems to bring a tragic end to the story. Suddenly trumpets announce the resurrection and Mazeppa rise as a king in a glorious coda in D major. Added to the closing of the score is the quote from Victor Hugo: "il tombe enfin et se releve roi" ("he falls at last and raises as king"). Etude No. 5 (Feux Follets - Irrlichter) in B-flat major The Etude No. 5 in B-flat major: "Feux Follets" is a gleaming, almost impressionistic goblins dance. A "leggiero" etude in perpetuum mobile. The theme is based on an alternating succession of the intervals of major and minor seconds. This is turn creates an undulating motion in double notes. Altogether the perception of vertical harmonies are loosened while the feeling of the tonality center is weakened too. Harmonically, this Etude is one of the most advanced of the series. The most audacious harmonic innovations of the composer, which are to come only several decades later in his life, are present here in an embryonic form. Etude No. 6 (Vision) in G minor In one totally different concept of piano writing, the strong Etude No. 6 in G minor: "Vision" is a bravoura piece in wide arpeges and tremolos. The "vision" here is dark and daunting as well as seemingly endless. Etude No. 7 (Eroica) in E-flat major Even though the developments of the brilliant ideas exposed in the introduction of the Etude No. 7 in E-flat major: "Eroica" may seem somewhat naive as compared with what Liszt will do with similar ideas ("heroic" themes) in his future works, the scope and power of this Etude is nevertheless remarkable. The "heroic" themes are fully developed and expanded using the widest possible keyboard range. The famous double octaves section is specially remarkable. Etude No. 8 (Wilde Jagd) in C minor With its typical imitations of the hunt horns, whip slamming, syncopated rhythms, strident, Berlioz-like (i.e. "La Damnation de Faust") harmonies, the Etude No. 8 in C minor: "Wilde Jagd - Wild Hunt", spreads as a demoniac journey. A middle section in E-Flat major, softer but still animated makes this large piece fit in an almost sonata form. Etude No. 9 (Ricordanza) in A-flat major The Etude No. 9 in A-flat major: "Ricordanza" is a youthful romance which is not as naive as it may appear at the first glance. The reworked version of 1851, while keeping the original naivete of the themes, makes it to a piece of deep lyrical poetry. Etude No. 10 (untitled – Allegro agitato molto) in F minor On hearing the first theme of Etude No. 10 in F minor, originally untitled – Allegro agitato molto, so-called "Appassionata", one can not stop remembering the theme of the Etude op.10 N.9 in F minor by Chopin. However the declamatory and warmly expressive theme develops here through all the range of the keyboard with brilliant intermediary sections and ends with an octaves coda in the purest "Lisztian" way. Etude No. 11 (Harmonies du Soir) in D-flat major The poetic atmosphere of the Etude No. 11 in D-flat major: "Harmonies du Soir" is in the purest "Lamartinian" style. Alphonse de Lamartine (1790- 1869) was a French writer, poet and politician who was instrumental in the foundation of the Second Republic. This particular sensitivity is both contemplative and captivating. The piece deploys on large range chords sometimes built on resonating bells-like basses. One "elegiac" middle section in E Major creates a "crepuscular" atmosphere of a rare beauty. Etude No. 12 (Chasse-Neige) in B-flat minor The Etude No. 12 in B-flat minor: "Chasse-Neige" is a sound-scape depicting a pale and heavily loaded sky. Fast and light chromatic runs as well as many tremolos notated with small-size notes evoke large and small snow whirlwinds. The sound-scape evolves from the distant contemplation of a dark and menacing landscape to the most raging furious tempests.