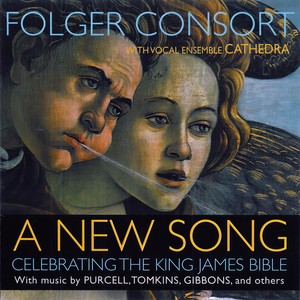

A New Song: Celebrating The King James Bible

- 流派:Classical 古典

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2011-12-09

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

“Sing unto him a new song; play skillfully with a loud noise” —Psalms 33:3 A New Song is Folger Consort’s first entirely new recording in eleven years. It was produced in 2011 as part of the worldwide celebration of the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible. Musical settings of biblical verse and other sacred works from the reigns of England’s James I and James II by composers Henry Purcell, Thomas Tomkins, Orlando Gibbons, and John Blow are complemented by instrumental fantasies and lively dances by Purcell, Gibbons, and Giovanni Coprario. This recording was part of the worldwide celebration of the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible, including an exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Manifold Greatness: The Creation and Afterlife of the King James Bible. www.manifoldgreatness.org FOLGER CONSORT Robert Eisenstein & Christopher Kendall Artistic Directors Risa Browder, violin Robert Eisenstein, violin Christopher Kendall, lute, theorbo Adam Pearl, organ Alice Robbins, viol, basse de violon Henry valoris, viola CATHEDRA Washington National Cathedral’s Chamber vocal Ensemble Michael McCarthy, Director Soprano Crossley Hawn Susan Lewis Kavinski Emily Noel Alto Kristen Dubenion-Smith Christopher Dudley Roger Isaacs Tenor Lawrence Reppert Aaron Sheehan Matthew Smith Bass Scott Auby Richard Giarusso Benjamin Park EARLY IN HIS REIGN, KING JAMES I convened a conference at Hampton Court to allow the Puritans to air their grievances. While James turned out to be unsympathetic to many of their issues, he did agree to a new English Bible, to be translated by a committee of about four dozen scholars from both the traditional Church of England hierarchy and the Puritan camp. The result of their efforts is one of the most important books in modern English. We have centered our musical celebration of this great work on settings of biblical texts from the realms of King James I and King James II. In the case of the former, we present anthems based on English translations that preceded the King James version, many of which were important sources for the committees of scholars. For instance, the Tyndale Bible of around 1530 provided a large portion of the language that was eventually adapted. It is difficult to find 17th-century musical settings of the King James Bible version of the Psalms because Coverdale’s beautiful prose from his 1535 print—the first printed Bible in English—made its way into the Book of Common Prayer, which was still in use throughout our chosen period. By the time of the Restoration, most English settings of biblical texts other than the Psalms were taken, sometimes with a bit of variation, from the King James version, which is apparent in our selections of anthems by Henry Purcell and Pelham Humfrey. We perform these works with the forces most commonly used for anthems in the 17th century-a small choir supported by organ and strings that accompany the verses and provide an opening symphony and instrumental interludes. THOMAS TOMKINS (1572-1656) was the son of a chorister at St. David’s Cathedral in Pembrokeshire. As such he probably got his early musical education as a boy treble under his father’s guidance. He studied with the great William Byrd, and we know from annotations in his copy of Thomas Morley’s A Plaine and Easie introduction to Practicall Musicke that he studied it carefully. By 1620 Tomkins was a member of the Chapel Royal, where his colleagues included Orlando Gibbons. When David heard is probably his best known anthem. On the point of imitation for the words “Would God I had died for thee,” the initial interval for the words “Would” and “God” is an ascending half step, but in successive entrances it grows to a third, a fourth, and then an aching minor sixth. When David heard and Be strong and of a good courage are full anthems, in which the full choir sings all the time. Orlando Gibbons’ anthem This is the record of John, on the other hand, is a verse anthem, in which a soloist or soloists alternate verses with full sections. These are the sorts of pieces that in the later 17th century expand to quite large works with instrumental symphonies and ritornelli, as well as multiple verses alternating with chorus sections. Roger North described GIOVANNI COPRARIO as “plain Cooper [who] affected an Italian termination.” Known variously as Cooper, Cowper, Coprario, or Coperario (bca. 1570-80? d 1626), the composer may indeed have lived for a while in Italy. Before 1620 or so he was associated with the royal court and wrote music for various court masques before joining the household of Prince Charles. Tradition has it that he taught music to James I’s children—historian Charles Burney says that Prince Charles “was a scholar of Coperario, on the viol da gamba.” If so, he taught well, because according to the printer Playford, Charles could “play his part exactly well on the Bass-viol” in Coprario’s suites. In the suites included here there are two violin parts, a perhaps princely bass viol part, and an independent organ part (here assisted by lute). These are among the first pieces to combine the viol with violins, an important step on the way to the later English court orchestra. ORLANDO GIBBONS (1583-1625) grew up and worked for much of his life in Cambridge, but he was born in Oxford to a large family of musicians. Gibbons was appointed to the Chapel Royal around 1603. By 1625 he was listed as the senior organist. Gibbons, like many of his contemporary university and court musicians, probably learned to play the viol as a child or young man. He certainly left us many fantasias for the instrument, as well as keyboard music, madrigals, and his church music. All three of our early 17th-century composers knew each other well since they all were associated with the royal court and chapel. When the 16-year-old Charles became the Prince of Wales in 1616, Gibbons and Coprario were among the musicians who formed his musical establishment. HENRY PURCELL (1659-1695) must be considered one of the greatest composers of the Baroque and certainly one of the greatest English composers of any era. The Restoration was a great impetus for musical development in England. Not only were many of the pre-Commonwealth court composers beyond their prime, but the taste of the court of Charles II and even more so that of James II tended toward the continental music they had been exposed to in exile. The days of the relatively insular English traditions of instrumental and vocal music were over as it became fashionable to incorporate French and Italian elements into the English tradition. As Dryden observed in his dedication to Purcell’s Diocletian (1690), English music was “now learning Italian, which is its best Master, and studying a little of the French Air, to give it more of Gayety and Fashion.” Purcell left us only a couple of full anthems, including I was glad, written for the coronation of James II. This five-part piece shows that Purcell was well-versed in the native polyphonic choral tradition as well as newer continental styles. However, most of his anthems are in the verse form and have instrumental symphonies. We can credit Charles II for this as he insisted on adding instrumental accompaniment to verse anthems. Charles was “a brisk, & Airy Prince, comeing to the Crown in the Flow’r & vigour of his Age,” according to Thomas Tudway, one of Purcell’s fellow choristers, and was “tyr’d with the grave and Solemn way, And Order’d the composers of his Chappell to add Symphonys &c with Instruments to their Anthems.” My beloved spake is certainly one of these and is the earliest surviving anthem by Purcell with symphonies. It is a wonderfully youthful and fresh example of Purcell’s art, with frequent changes of meter, lush full choruses, and charming dance-like ritornelli for the strings. It is a fitting way to begin our recording. There are two surviving sets of sonatas by Purcell, a form he considered “the chiefest Instrumental Musick now in request.” He found in the Italian trio sonatas he studied a good deal of contrapuntal skill and “a good deal of Art mixed with a good Air, which is the Perfection of a Master.” His Ten Sonatas in Four Parts, from which our selections here are taken, was printed posthumously in 1697, and the works are scored for two violins, viol, and harpsichord or organ. Unlike the more progressive trio sonatas of Corelli, in which the string bass mostly plays the same bass line as the harpsichord, the viol in Purcell’s sonatas has independent figuration and contributes to the counterpoint on its own. These sonatas tend to consist of five or more short contrasting sections and are full of contrapuntal artifice, lively canzonas, and affecting and graceful slow movements. JOHN BLOW (1649-1708) was the organist of Westminster Abbey from 1668 to 1679, when he resigned so that his pupil Purcell could take the position. The Ground performed here is a lovely example of his music for keyboard. Blow is most famous for his court entertainment Venus and Adonis, considered by many to be the first English opera and certainly a model for Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. PELHAM HUMFREY (1647-1674) was a forward-looking musician who did not compose anything in the old polyphonic style. He traveled to France and Italy and seems to have been the first English composer to incorporate Italian and French techniques in his music. Hear, O heav’ns shows Italianate influence and contains some operatic dialogues among the soloists in the verses. We conclude our recording with an anthem for the next rulers of England after James II. PURCELL’s Praise the Lord, O Jerusalem was composed for the coronation festivities for William and Mary at Westminster Abbey in 1689. —Robert Eisenstein