- 歌曲

- 时长

简介

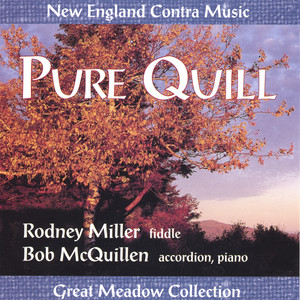

RODNEY MILLER and BOB McQUILLEN PURE QUILL Rodney Miller Fiddle Bob McQuillen Piano, Accordion ----------------- PURE QUILL is an old New England expression meaning “the genuine article… the real thing.” Here you have it with Rodney Miller, New England’s foremost fiddler teamed with Bob McQuillen, legendary contra piano player and composer of over 1000 contra tunes. This recording captures the two as they might sound at Peterborough N.H. Town House on contra dance night. All that’s missing is the merry clop of a few hundred feet. For McQuillen and Miller both, the secret to contra’s continued vibrancy is that the future and the past are not adversaries, but fellow travelers. And the dance itself remains their greatest teacher. ----------------- PURE QUILL Contra dance music is nearly unique among traditional instrumental genres in that it continues to exist primarily as a dance form. While this venerable New England folk dance is enjoying broader popularity now than at any time in its history, its revival has come not on the concert stage, but the dance floor; in town halls, dance societies and festivals throughout North America, Europe and Asia. Leading the charge is Yankee fiddler Rodney Miller, whose seminal “New England Chestnuts” recordings still form the contra revival’s core repertoire. With his adventurous “Airplang” records and the more recent “Airdance,” he has also led the way in presenting contra tunes in ensemble settings for pure listening pleasure. Here, Miller enjoys a lifetime dream come true: a duet record with one of his chief contra music heroes and mentors, accordion and piano player Bob McQuillen. Now a vigorous 76, McQuillen, or “Mac” as his friends call him, has been at the epicenter of the contra resurgence since joining the legendary Ralph Page Orchestra in 1947. “Mac is an anchor in the contra dance scene.” Miller says. “There’s a real rootedness to his very distinctive piano style. Playing with Mac, I stay closer to home. He lays down such a solid rhythmic foundation, not traveling far distances in the chord structure, that my improvisation tends to be more subtle.” This recording captures the two as they might sound at Peterborough, N.H. Town House on contra dance night. “Pure Quill,” in fact, is an old New England expression meaning the genuine article. All that’s missing is the merry clop of a few hundred feet. McQuillen lays down a granite floor of cadence – listen to his bold opening chords for “I Don’t Love Nobody.” But then hear how his plucky strut evokes a delightful sassiness from Miller’s fiddle. With strains of a Chinese folk melody, McQuillen sets a delicate mood for “Gem Varsoviana.” It is constantly evident how much these two enjoy each other’s musical company. Fiddle and accordion commiserate over the 18th-century Scottish air, “Lowlands of Holland.” And they have grand, hokey fun with the old vaudeville novelty, “Huskin’ Bee.” “ We speak the same language in ways you don’t with people you have not played with so much.” Miller says. “It’s not just the same words; it’s the same dialect.” When they met in 1970, McQuillen was already among contra’s most seasoned veterans and finest composers (several of his tunes are here, including the darkly pretty “Elvira’s Waltz,” written for Miller’s daughter, now a fine contra player herself.) The contra revival was just underway, thousands of young novices flocking to the old dance. The Canterbury Country Dance Orchestra, where Miller got his start, was founded by Dudley Laufman to make the music stage as welcoming to newcomers as the dance floor. Guest musicians were always welcome, the ranks often swelling to more than thirty. In the midst of that, a strong rhythm section was crucial, and in contra, the piano often is the whole rhythm section. McQuillen was the perfect man for the job, his chops sharpened from years playing accordion alongside Johnny Trombly’s authoritative piano in the Ralph Page Orchestra. Page was to contra dance music what Bill Monroe was to bluegrass, its chief exponent and most definitive performer. McQuillen had begun haunting New Hampshire contra dances after mustering out of the Marines following World War Two. He fell in love with the friendly mix of sociability, dance and music. After just one night sitting in with Page’s orchestra, he was hired as its accordionist. Since then, he has been in constant demand at dances, in addition to a long career teaching at Contoocook Valley Regional High School in Peterborough, N.H. He says he enjoys how much less formal – and more social – the dances have become in recent years. (Insert Page 4 of 4) “The dancing is less stiff, more of a free expression of joy through movement. They’re having the time of their lives, so I find no fault with what the dancers are doing. So long as they’re not hurting their neighbor, why, they can do as the damn please – that’s my version of it.” McQuillen is to Miller what traditional music is to most of us; a touchstone to times past, a melding juncture where the best instincts of that past flow freely into the fleeting present. “After I’ve made excursions with other bands,” Miller says, “coming back to Mac I always know what to expect – that reverence for the tradition mixed with his very outgoing nature, the way he has of personally reaching out to dancers.” McQuillen says, “I am still pretty fussy about tempos. That’s certainly something I got from Ralph. He never wanted to see it get too fast. If it gets too fast, it gets too excercize-y, too aerobic. The music wants to be that way to a degree, but it has to be slow enough to be social for the dancers. The emphasis is not on how fast can you do it, the emphasis is on how much fun are you having.” For McQuillen and Miller both, the secret to contra’s continued vibrancy is that the future and the past are not adversaries, but fellow travelers. And the dance itself remains their greatest teacher. Scott Alarik Special thanks for research by Jack Beard. -----------------