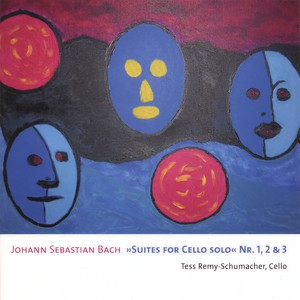

Johann Sebastian Bach Suites For Cello Solo Vol I

- 歌唱: Tess Remy-Schumacher

- 作曲: Johann Sebastian Bach (约翰·塞巴斯蒂安·巴赫)

- 发行时间:2006-01-01

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

-

作曲家:Johann Sebastian Bach( 约翰·塞巴斯蒂安·巴赫)

简介

Cellist Tess Remy-Schumacher was born in Cologne, Germany, and has studied with Boris Pergamenshikov, Maria Kliegel, Siegfried Palm, Jacqueline du Pre, and William Pleeth. As a Fulbright scholar, she studied with Lynn Harrell in his Piatigorsky Class at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, where she was awarded her Master of Music. As “most outstanding graduate of the year for performance, academic excellence, and leadership,” she received her doctorate under the supervision of Eleonore Schönfeld. Tess Remy-Schumacher has won first prizes in Germany’s Jugend musiziert, New York’s International Artist Competition, and Rome’s Carlo-Zecchi Competition. She has performed in Asia, Australia, Europe and the United States, including Wigmore Hall, London; Jubilee Hall, Singapore; Carnegie Hall, New York (1995, 2005); and Bradley Hall, Chicago. She has performed and taught at the Brisbane Biennial Festival, the Australian Festival of Chamber Music, the Contempofest (Australia), the Weathersfield Music Festival (USA), the Internationaler Klaviersommer (Germany), Phillips Andover Academy, and the Encore Music Festival (USA). In The New York Concert Review, Edith Eisler wrote of her 2005 Carnegie Hall recital, “Ms. Remy-Schumacher’s technique is disciplined… Her bow control and mastery of the fingerboard are complete; her intonation is excellent.” Dr. Remy-Schumacher has recorded for WDR, NDR, and MDR (Germany), WNYC (New York), K-USC (Los Angeles), ABC National (Australia), MBS-FM (Melbourne, Australia), and Swiss and Italian television. CDs include her own transcriptions of Schumann's Dichterliebe with Marcus Reissenweber and Christoph von Sicherer (HOME 98106); works by In Sun Cho for the Contemporary Music Society, Seoul; works of Villa-Lobos with guitarist Stefan Grasse (Xolo 1001); the Ibert Cello Concerto (recorded at Radio Hilversum) with solo cello works by Henze, Lutoslawski, Stahlke and Magrill (Xolo 1002); the Rachmaninov Sonata in with pianist Michael Staudt (Xolo 1004); cello works by Sam Magrill (Xolo 1006); and chamber works by Brahms and Magrill (Xolo 1008). She has just released the first volume of J.S. Bach Suites for Solo Cello (Xolo 1012) and Trios by Tchaikowsky and Beethhoven with Judith Lee and Christopher Cooley. Following her appointment at James Cook University from 1992-98, she has been Professor of Cello and Chamber Music at the University of Central Oklahoma. She is a Visiting Fellow at Harvard University, Cambridge, for the academic year 2010/2011. She plays a violoncello by Goldfuss Regensburg 2005. www.tessremyschumacher.com Recording engineer Hermann Heinrich, born in 1965 in Regensburg, Germany, is internationally known for his recordings of instrumental, vocal, orchestral, and choral music. He holds degrees in Cello Performance (with Sigmund von Hausegger) and Education from the Musikhochschule Munich, and performs frequently in concerts as cellist and bassist. Bach’s suites for unaccompanied violoncello are unquestionably a great monument of artistic genius, but this does not do them justice—or at least not full justice—for monuments are of two kinds. Those such as the temple of Karnak or the Washington Monument are designed to produce in the observer a sense of awe at the greatness of their subject, with a corresponding decrease of the observer’s own sense of significance. A better analogy for Bach’s suites lies in the Parthenon, whose every dimension and proportion is designed not to alienate and diminish the observer, the “ordinary human,” but to draw that person in and produce a human-scale relationship with the work of genius. Bach’s work is of the latter sort of monument, which is also arguably the product of greater genius than the former. The cello suites, written about 1720, belong to the composer’s “Cöthen” period, that time during which he served as Capellmeister to the prince of Anstalt-Cöthen. In this position he was essentially responsible for the court’s entire musical establishment. There is some dispute among scholars as to whether Bach composed the suites for the Cöthen court’s outstanding cellist, Christian Bernhard Lienicke, or for its viola da gambist, Christian Ferdinand Abel. Whichever may be the case, it is clear that the musician must have possessed astounding ability. At that time the cello was most commonly utilized as a bass instrument, providing harmonic foundation, whereas Bach demands of the instrument a virtuosity that still taxes the modern performer in both technique and musicality. This amazing virtuosity and musicality Bach poured into the simple form of the instrumental dance suite. The baroque suite was a group of stylized dances ordered in a standard succession. The kernel of the suite’s members seems to have evolved during the seventeenth century and to have regularized as embracing the allemande, courante, and sarabande. The enlarged baroque form of the suite expanded the original trio with an opening prelude and a closing gigue, which latter was preceded by an optional movement, often a minuet. This created a six-member form of prelude, allemande, courante, sarabande, optional movement, and gigue, known by the un-euphonious acronym of PACSOG. Bach maintains this succession, most often filling the optional position with a pair of minuets, bourées, or gavottes. All the movements, save the preludes, are simple binary movements, heightening the paradoxical juxtaposition of simplicity and genius. A description of the basic characteristics of the dance forms that Bach inherited does less to inform than to astonish the listener that such simple forms and rhythms could have provided the vehicle for music of such depth and rich diversity. The allemande or “German dance” began as a simple dance in duple meter whose tempo might vary widely. Perhaps because of this, the dance by Bach’s time retained little distinctive character and had come to serve more as a vehicle for idiomatic instrumental writing, usually emphasizing ongoing imitation. The French courante, or corrente in its Italian version, was a triple meter dance, stately among the French but more sprightly among the Italians. In Bach’s time the two versions of the name were used without distinction. The most distinctive trait of the sarabande is its characteristic elaborate use of ornamentation within the context of a slow and stately tempo in triple meter. In the first two suites Bach provides a pair of minuets in the “optional” position. The minuet is surely the best known of all the stylized dances because of its long survival in a variety of musical genres. Its triple meter and simple unaffected melodic style are usually immediately recognizable. The third suite replaces the minuet pair with a pair of bourées, somewhat more sprightly than the minuet and with a lively rhythmic energy in duple meter. The gigue that concludes each suite is a dance that possesses a pedigree both intriguing and surprising. Behind the somewhat pretentious spelling of its name and the lively duple rhythms that seem to indicate the French court lies, in fact, the humble jig of the British Isles country dance. Its typical infectious rhythms and engaging melodies are actually owing to its folk origins. The previous omission of any mention of the prelude is deliberate. The prelude was, as indicated above, a later addition, and it is the only movement whose origin lies not in the dance. The preludes are introductory flourishes that lend greater weight to the following succession of dances. Even so, they are often among the more memorable music in the suites. Indeed, the prelude of the first suite without question ranks among the most readily recognized of all musical compositions, having served the modern mass media in film scores, television and radio background music, and even commercials. The fact that such use has in no degree brought about the slightest diminution of the greatness of the music is perhaps a small but significant indication of the opening argument, that Bach achieved in the suites for violoncello profound works of surpassing art that have succeeded in remaining accessible to the simpler and more humble levels of human experience.