Beethoven: The Complete Works for Cello and Piano

- 流派:Classical 古典

- 语种:英语

- 发行时间:2012-06-27

- 类型:录音室专辑

- 歌曲

- 时长

Disc1

-

Sonata No. 1 in F Major, Op. 5, No. 1

Disc1

-

Sonata No. 1 in F Major, Op. 5 No. 1: II. Rondo

Disc1

-

Sonata No. 4 in C Major, Op. 102 No. 1

Disc1

Disc1

-

Sonata No. 3 in A Major, Op. 69

Disc1

-

Sonata No. 3 in A Major, Op. 69: II. Scherzo

Disc2

Disc2

-

Sonata No. 2 in G Minor, Op. 5 No. 2

Disc2

-

Sonata No. 5 in D Major, Op. 102, No. 2

Disc2

-

Sonata No. 5 in D Major, Op. 102 No. 2

简介

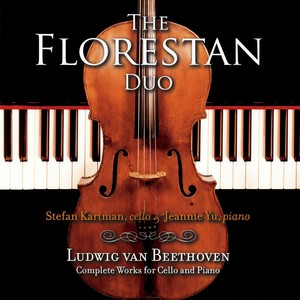

Ludwig van Beethoven Complete Works for Piano and Cello Sonata in F Major, Op. 5 No. 1 Adagio sostenuto - Allegro RONDO: Allegro vivace Sonata in C Major, Op. 102 No. 1 Andante - Allegro vivace Adagio - Allegro vivace Variations on Mozart’s “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” from Die Zauberflöte, Op. 66 Sonata in A Major, Op. 69 Allegro ma non tanto SCHERZO: Allegro molto Adagio - Allegro vivace Variations on Handel’s “See, the Conquering Hero Comes” from Judas Maccabeus, WoO 45 Sonata in G minor, Op. 5 No. 2 Adagio sostenuto e espressivo Allegro molto più tosto presto Rondo: Allegro Variations on Mozart's "Bei Männern welche Liebe Fühlen" from Die Zauberflöte, WoO 46 Sonata in D Major, Op. 102 No. 2 Allegro con brio Adagio con molto sentimento d’affeto The Florestan Duo - Stefan Kartman, cello and Jeannie Yu, piano Stefan Kartman, cello, and Jeannie Yu, piano, are two brilliant soloists whose passion for chamber music brought them together in 1987 during their studies at the Juilliard School of Music. Like-minded musicians who share the same concept of an ideal sound, musical expressiveness, and excellence, they carry on a tra¬dition whose lineage reaches directly back to the romantic period of Johannes Brahms. This tradition is the basis of inspiration for these shared ideals. Their first meeting occurred in the studio of violinist Joseph Fuchs as they studied Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio in C minor. They continued to study chamber music with Fuchs and sonatas with cellist Harvey Shapiro and pia¬nist Martin Canin until their graduation in 1989. Both members of the Florestan Duo have since earned their Doctor of Musical Arts degrees and have also worked with cellists Bernard Greenhouse and Zara Nelsova and pianists Susan Starr and Ann Schein, among others. Kartman and Yu have performed to critical acclaim in concert halls and educational institutions throughout the United States, Europe, and the Far East. Recordings of their performances have been aired on WQXR in New York, WFMT in Chicago, and WOI in Ames, Iowa. Most recently they have returned from critically acclaimed tours of Korea, Taiwan China, Holland, Italy, and China, including solo performances with the Xiamen Symphony and recitals as a duo in Xiamen, Jinmei, Shanghai, Soest, and Verona. Both members of the Florestan Duo are accomplished teachers of chamber music and solo repertoire, having served on the faculties of Drake University, Illinois Wesleyan University, the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music, the MidAmerica Chamber Music Institute at Ohio Wesleyan University, the Alfred University Summer Chamber Music Institute under the artistic directorship of Joseph Fuchs, the Milwaukee Chamber Music Festival, and the Green Mountain Chamber Music Festival under the artistic directorship of Kevin Lawrence. Kartman is associate professor of cello and chamber music at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Yu freelances in the Milwaukee and Chicago metropolitan areas. Sonata No. 1 in F Major, Op. 5 No. 1 Beethoven’s First Cello Sonata begins with a large slow introduction. While it wanders tonally somewhat, it fulfills the essential role of the introduction—to state the main key at the beginning, and to prepare for a return to that key as the Allegro begins. Scholars have pointed to Mozart’s Violin Sonata in G major, K. 379, as a possible model for this introduction. To be sure, Mozart’s introduction is of similar breadth and tonal plan, and we must remember that Beethoven’s principal models for writing cello sonatas—lacking earlier works for cello with a written-out (i.e., not basso continuo) keyboard part—were Mozart’s sonatas for violin and piano, which number around twenty. Beethoven’s Allegro begins with a long theme, reminiscent to the large theme in the same position in his Septet in E-flat, Op. 20, presented first by the piano and them taken up by the cello. The two sonatas of Op. 5 are vehicles for Beethoven as a young piano virtuoso, written during his stay in Berlin during a concert tour in the spring and summer of 1796. He has given himself, as well as the cellist with whom he was working, Jean Louis Duport, passages of considerable virtuosity. The astute listener will notice passages strikingly similar to portions of Mozart’s piano sonatas K. 333 and 570. The movement concludes with a substantial coda which, after the tempo slows to Adagio, turns to a cadenza-like passage, ending with the traditional trill, and reinforcing the virtuoso nature of the work. There is no slow movement. Perhaps the large slow introduction rendered one unnecessary, or perhaps Mozart’s several two-movement violin sonatas served as models. The second and final movement, a rondo, begins without stating its main key clearly, an approach Beethoven also utilized in both movements of the Second Sonata, Op. 5 No. 2 (and Mozart did similarly in the Violin Sonata in C, K. 303, first movement, in the Molto allegro). The writing, again, calls for virtuoso players, and there are marvelous passages in which the cello sustains an open fifth drone while the piano plays an arpeggiated idea. Slower tempos near the end lead to a brilliant conclusion. Sonata No. 4 in C Major, Op. 102 No. 1 “It is so original that no one can understand it on first hearing.” So wrote Michael Frey, Hofkapellmeister at Mannheim, about Beethoven’s Fourth Cello Sonata. The autograph manuscript of the sonata is dated “toward the end of July 1815,” and he titled the work a “free sonata.” That it is freer than its companion, Op. 102 No. 2 (titled simply “sonata”), is evident in the respective layout of the sonatas’ movements. While no. 2 is a conventional fast-slow-fast cycle, no. 1 is organized most distinctively. The sonata begins with the cello alone, like the Third Sonata, Op. 69, presenting an idea that comes to take on considerable significance in the totality of the work. The tempo is Andante, and the passage gives way to a concise Allegro vivace in sonata form. Yet the introduction is tonally very unconventional. It ostensibly begins in the home key, though the key of C is not stated explicitly at the beginning. And the introduction ends in the tonic, not the conventional dominant—but the Allegro vivace that follows is in A minor, not C major, and the structure that ensues is in keeping with the traditional treatment of A minor. The music that follows appears initially to be the slow movement. Marked Adagio, it is replete with ornamental gestures, and proves to be more an interlude than a full slow movement. (The only true slow movement in Beethoven’s cello sonatas is in the Fifth Sonata, Op. 102 No. 2.) This Adagio, only nine measures long, gives way to a return of the material that began the sonata, a cyclic return of seven measures that leads to the finale, a lighthearted sonata form movement in the home key of C. Its fugal development section might be viewed as a counterpart to the fugal finale of Op. 102 No. 2. Further, the overall shape of the Fourth Sonata, including the cyclic return of its opening idea, is also to be found in the Piano Sonata in A major, Op. 101, written in the same period, and it has been suggested that the works that comprise Beethoven’s Opp. 101 and 102 comprise a trilogy. Variations on Mozart’s “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen” from Die Zauberflöte, Op. 66 Beethoven composed this first of his two sets of variations on a theme from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte in 1796, in the same period when he wrote the two cello sonatas Op. 5, and it was published in Vienna in 1798. The passage from the opera that he selected appears late in the second and final act. It is a catchy, strophic song for Papageno, the bucolic and comic figure of a bird-catcher who is an amusing and gently annoying character during the opera, ever since his initial appearance in the second number of act I (“Der Vogelfänger bin ich ja”). In “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen,” Papageno pines for a girlfriend—and it works, as Papagena enters just as the aria concludes, appearing initially as a hag, and then transforming into a beautiful young woman—only to be taken from him, as he is not yet worthy of her. Beethoven’s variations retain the original key of F, though the melody is rewritten in some details. There are 12 variations, and the piano plays the first one alone. The basic shape of the theme’s opening forms the basis of variations numbers 2 and 4. No. 5 focuses on the dotted rhythms of the theme. Variation 10 is in F minor, and it is noteworthy that No. 11 is also minor, breaking with the tradition of including just one minor variation. This is a run-on variation, leading into the large, final one, and it ends in quiet serenity—perhaps indicative of Papageno’s “happy ending,” when he earns his sweetheart late in the opera. Sonata No. 3 in A Major, Op. 69 Beethoven completed his third cello sonata by mid-1808, and when Breitkopf und Härtel published it in April 1809, it was dedicated to Baron Ignaz von Gleichstein. The Baron was a cellist and close friend of the composer in the period 1807-11, a friend instrumental in obtaining Beethoven’s annuity from Prince Lichnowsky. The Op. 69 sonata dates from a period when Beethoven wrote such seminal works and the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies and the two piano trios of Op. 70. History has judged this sonata one of Beethoven’s great masterworks, and it has come to hold a central position in the repertory of music for cello and piano. The sonata begins, like Op. 102 No.1, with the cello alone, singing a beautiful line that has considerable consequences for the rest of the movement, which the piano answers and then repeats in octaves. Then, the piano presents a new idea in A minor, starting with the same A-E ascent as the opening solo. It is a bold and powerful theme, marked by offbeat accents. The secondary theme is a duet: the cello’s part is scalar, while the piano’s is rhythmically derived from the opening solo—and soon the players exchange these roles. Before the end of the exposition, a brilliant new idea in E major appears in the piano, marked by colorful chromaticism and accompaniment by the cello’s pizzicato. When the solo opening returns in the recapitulation, Beethoven characteristically transforms it by accompanying with piano triplets. A substantial coda serves further to develop the solo opening idea. The second movement is a scherzo, a break with the convention of a slow movement in this position. In A minor, it is distinctive in presenting the trio section in A major twice—scherzo-trio-scherzo-trio-scherzo—a form Beethoven used only occasionally that turns away from the usual scherzo-trio-scherzo form. Then we hear what we take to be a slow movement in E major. The piano presents a lyrical theme, and then the cello takes it up. But there is no more, as the finale begins. What appeared to be a slow movement seems in the end more an interlude or introduction. The finale, in sonata form, is a movement fully worthy to conclude this brilliant sonata. Its secondary idea is a rhythmically fascinating dialogue between a short cello idea and the piano’s answer in eighth-note chords. A large, impressive coda closes the work. Variations on Handel’s “See, the Conquering Hero Comes” from Judas Maccabeus, WoO 45 Beethoven thought very highly of Handel. He was exposed to his music as he attended the gatherings hosted by Baron van Swieten in his early years in Vienna; Mozart, who had also attended, said of these performances that “nothing is played but Handel and Bach.” In 1817 an English musician named Cipriani Potter asked Beethoven to identify the greatest composer of the past, and he replied “Mozart and Handel.” (That same year he declared Cherubini the living composer he most respected.) His friend Edward Schulz reported that Beethoven told him in 1823 that “Handel is the greatest composer that ever lived.” Beethoven owned a considerable amount of Handel’s music in manuscript score, and composed an overture called Die Weihe des Hauses (Consecration of the House), Op. 124, in the style of Handel in 1822. It is no surprise, then, that Beethoven should select a celebrated chorus by Handel for one of his three sets of variations for cello and piano. These variations, like the two sonatas of Op. 5, were apparently composed during his stay in Berlin in 1796, and all three works were then published in Vienna the following year. He dedicated the variations to Princess Christine, the wife of his patron Prince Karl Lichnowsky, and the hero mentioned in the text may be meant to refer to the Prince. Judas Maccabaeus is usually considered the second most popular of Handel’s oratorios, after Messiah, and it received its very successful first performance on April 1, 1747. In Beethoven’s twelve variations he achieves a considerable variety, both rhythmically and texturally. The first variation is scored for the piano alone. In the second, the piano maintains an accompaniment pattern while the cello sings a slower line derived from Handel’s theme. The fast-moving piano part of the third variation is harmonized in slow-moving cello arpeggiation. The fourth and eighth variations turn to the minor mode. The penultimate variation’s Adagio marking sets up the quick final variation, in which the meter changes to 3/8, and the work ends as the players engage in a short canon beneath a long piano trill. Sonata No. 2 in G Minor, Op. 5 No. 2 Beethoven moved to Vienna from his native Bonn in Spring 1792, roughly half a year after Mozart’s death. In the course of the next several years, he actively composed and played the piano, establishing himself as both composer and keyboard virtuoso. In that vein, Beethoven undertook a concert tour in February to July of 1796, at the age of 25. Over the course of the tour, he visited Prague, Dresden, Leipzig, and Berlin. During his month-long stay in Berlin, he composed two cello sonatas. His selection of the cello was no accident: King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, with his seat in Berlin, was a music-loving king who played the cello and allotted a portion of each day to chamber music. In collaboration with the king’s first cellist and cello teacher, Jean Louis Duport, Beethoven performed the brand new sonatas for the king during his stay in Berlin. The second sonata, in G minor, is a distinctly original and innovative work. It begins slowly, with a passage in the manner of a slow introduction. But this section is so substantial as to put its identity into doubt: its tonal variety and range of materials suggest that is may better be viewed as its own entity. That section gives way to a fast G-minor movement in sonata form, noteworthy for its off-key opening (on V7 of iv). The ensuing movement is among Beethoven’s longest—more than 500 measures—and ends in the major. There is no slow movement; perhaps it was obviated by the initial slow section. The sonata concludes with a sprightly, comic sonata-rondo in G major. It too begins off key, on C major, and Beethoven returns to this key for his bold, triadic second episode. Just prior to the next statement of the main theme, the piano presents a false return in D-flat, and when the tonic return does take place, Beethoven sets it over a dominant pedal. The movement ends brilliantly with a substantial coda. Variations on Mozart’s “Bei Männern welche Liebe fühlen” from Die Zauberflöte, WoO 46 Composed in 1791, Mozart’s German Singspiel Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) was first performed in Vienna just over three months prior to the composer’s death at age 35. It is one of just two major operas by Mozart with a libretto not in Italian; the other, also in German, is Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio). Both these operas—as well as Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio—belong to the Singspiel tradition, in which spoken dialogue replaces the recitative of Italian opera. As with Fidelio, there is an element of rescue in the plot of Die Zauberflöte. The male hero, Tamino, learns early on that a young woman named Pamina has been abducted, and Tamino falls in love with her portrait as he vows to rescue her. Pamina makes her first appearance—except for the portrait—late in the first act, when she is in the company of the bird-catcher, Papagano, and this is the passage that Beethoven selected for his variations. “Bei Männern” is a duet in 6/8 meter for Pamina and Papageno that speaks in praise of love, of husband and wife; it is one of several musical numbers in Die Zauberflöte that serves to teach a moral lesson. Beethoven’s variations were composed in 1801 and published in Vienna in 1802. He dedicated the work to one of his early patrons, Count Johann Georg von Brown-Camus, also the dedicatee of the string trios Op. 9. Beethoven retains the original key of E-flat for his seven variations. The cello and piano are treated very equally, engaging in dialogues in the variations that seem to refer to the duet texture of the original. It is traditional in classical variations that one variation be set in the mode opposite that of the theme, and Beethoven observes this convention in Variation 4. Thereafter, the composer alters the original tempo; in Variation 5, it increases, Variation 6 is marked Adagio, and then Variation 7 is faster again. This final variation closes the work with a substantial coda, ending with the main tune presented with imitative entries, seeming once again to refer to the duet texture of the original. Sonata No. 5 in D Major, Op. 102 No. 2 Historians have long divided Beethoven’s compositional career into three large periods, early, middle, and late, and have often pointed to the Piano Sonata Op. 101 and the two cello sonatas Op. 102 as the works that began the late period. These last two cello sonatas, comprising Op. 102, were dedicated to Countess Marie Erdödy, a good pianist and friend of Beethoven, and were published in Bonn by Simrock in 1817. These are Beethoven’s last duo sonatas and his last chamber music with piano; some have suggested that the now-deaf composer was no longer interested in the social music-making inherent in such works. Beethoven composed the final sonata, according to his notation on the autograph, at “the beginning of August 1815.” The work begins with a fast movement in sonata form, containing a striking false recapitulation just prior to the tonic return that functions as the structural recapitulation. The writing is economical, and the sonatas of Op. 102 are considerably more brief than the earlier ones. The D-minor slow movement is remarkable, beyond its very poignancy, as being the only full slow movement among Beethoven’s five cello sonatas. And it gives way, with no full pause, to the finale, a full-fledged four-voice fugue in D major, interestingly incorporating the inversion of its subject. As a work seen as initiating Beethoven’s late period, the presence of a fugue is significant: fugal texture takes on a major role in his late works—recall, for example, the piano sonatas Opp. 101, 106, and 110, and of course the Grosse Fuge for string quartet, Op. 133. One wonders to what extent this gesture led to Brahms’s decision to close the first of his two cello sonatas with a fugue. Beethoven’s erudite, contrapuntal finale is a powerful farewell to his work in the realm of the duo sonata. Program Notes by Dr. Timothy Noonan, University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee ©2012 Stefan Kartman. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication of this recording is a violation of applicable laws.